Protestors march through a fancy business luncheon, holding signs saying “on strike” and decrying intimidation tactics.

A labor strike in 1920? Or part of Occupy Wall Street in 2011?

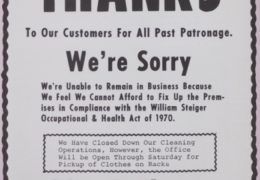

Neither—it’s 1971, and the protestors, like the people watching, are business owners in suits and ties. Their message: business, not labor or “the people,” has become the oppressed class in the United States.

Activists like these, says UNC historian Ben Waterhouse, are a large part of the reason why U.S. politics turned away from the progressivism of the 60s to the conservatism of the 80s. His new book, Lobbying America, describes the 70s as a time when business leaders felt ganged up on and decided to fight back. But how could a relatively small coalition change the political direction of the whole country?

Traditionally, Waterhouse says, historians thought of the period after 1964, when Republican Barry Goldwater lost in the most lopsided presidential election ever, as a low point for American conservatism, not ending until Ronald Reagan’s presidential campaign of 1980. Only in the past 10 years, he says, have historians started to take the 70s more seriously. “The cultural view is that the 60s were the party, and the 70s were just awful,” Waterhouse says. “People were disenchanted. But that’s exactly what makes the 70s so important.”

Following Vietnam, Watergate, and a series of economic recessions, people felt mistrustful of government. Yet at the same time, the federal government was increasing its influence. Regulations came into force from the Clean Air Act and Clean Water Act, as well as from legislation governing pharmaceutical testing, safety for baby products, food nutrition information, and much more.

Many people were in favor of all this. “Big government” regulation could have kept increasing, Waterhouse says. But then something changed: big businessmen realized that they could work together.

“Before this time, most regulations had clear winners and losers, and the losers were different industries,” Waterhouse says. “If the government made a regulation about railroad companies, usually it privileged one railroad company over another, or existing rail companies over people who wanted to get into the game.

“The environmental and consumer-rights movement changed that calculus, because the interest group that was supposed to be protected was the public. For example, if you decide that DDT can’t be sprayed on a field, it’s the business community that bears the cost of that.” This change in the nature of regulation unified business interests in a way they’d never come together before—big business, small business, and within and across industries.

Literally in a smoke-filled back room—in the 70s, it had to be smoke-filled, Waterhouse says—executives came together to decide how to stem the anti-business tide. They formed the Business Roundtable, about which Waterhouse knew nothing when he started his research as a graduate student at Harvard. Nor did other historians he read make much more than passing reference to the organization. It still exists as a coalition of about 200 CEOs, so Waterhouse wrote to the president of the organization and asked if he could come visit the archives in Washington, DC.

He heard back, and the Business Roundtable said that it didn’t normally let people into the archives, but the organization had reconsidered that policy, and he was welcome to come. On his next school break, Waterhouse drove down to the Business Roundtable’s K Street office, where he was led into a “fascinatingly disorganized” room full of papers—the organization’s old case files. Later, he was shown all of the correspondence from the 70s. These documents gave Waterhouse a perspective on the business activism of the 70s that few other historians have had.

As he got acquainted with the businessmen of the 70s through their words, Waterhouse learned how they saw themselves and the country. Despite their wealth, he says, “they felt they were in a position of weakness. The political sands had shifted so completely under their feet. Their political opponents were very successfully pursuing policies that in their minds were going to hurt not only the bottom line, but also the strength of the American economy—which, in the context of the Cold War, also meant the security of the country.”

From 1965 on, inflation had picked up steam. This led workers to demand salary increases to keep up with rising prices. “But from the perspective of many managers, this is the whole problem,” Waterhouse says. “Why are prices going up? Because companies have to raise the price of the finished product in order to pay for the cost of labor. Every time labor asks for more money, they’re driving up production costs. And of course labor is saying: ‘Are you kidding? You guys are rich!’”

The Business Roundtable and its allies—the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the National Association of Manufacturers—succeeded in stopping legislation that would have allowed workers to engage in solidarity strikes with workers from other employers. “Picket lines are threats, not freedom of speech,” said Heath Larry, president of the National Association of Manufacturers. Then the three groups (called “the Big Three” in the press) successfully lobbied Congress to water down the Humphrey-Hawkins Act, which was supposed to increase employment and minimize inflation, but which business leaders were sure would keep driving inflation higher.

These days we think of business lobbying as normal, but in the 70s it was a big deal, Waterhouse writes. “For most of the postwar period, business leaders had been loath to engage too directly in the political process. Some considered politics unseemly; others believed lobbying was a job best reserved for public relations specialists. In the 1970s, however, longstanding political grievances reached a tipping point.” Businesses got more involved in direct lobbying, as well as spending more money on PACs and think tanks.

While this was going on, consumer activist Ralph Nader was lobbying the government, too—and in 1975, three-quarters of Americans approved of having him around to “keep industry on its toes.” After all, who doesn’t like clean air and water, safe food, and cars with seat belts?

The United States was on track to create a Consumer Protection Agency, Waterhouse says, to field complaints against business and to make sure other government agencies created regulations in the public interest. The Big Three organized companies in a national campaign of lobbying, letter-writing, advertising, and opinion pieces to kill the plan. The defeat of the Consumer Protection Agency “marked a sea change in politics,” Waterhouse writes. “In the course of less than ten years, the organized business community had taken what appeared to be a legislative slam dunk for public interest liberals and rendered it politically unviable.”

The Big Three’s aggressive lobbying, Waterhouse argues, may have been why Jimmy Carter’s administration tacked to the right over the course of his term from 1977 to 1981. “It’s clear that there was a lot of influence on him by members of business organizations,” Waterhouse says. “If he hadn’t been hearing from companies like DuPont and U.S. Steel, the shape of the Carter administration might have changed. And if Carter had a more successful term, then maybe he has a second term. And then maybe there’s no Reagan administration—ever. And then, who knows?”

By the time Reagan was in office, the political lobbying world was much more complex than it had been when the Big Three got together. More money and more lobbyists were going in different directions. And business owners in the 80s also faced the perils of winning, Waterhouse says. “These guys defined themselves by what they were against in the 70s. Once Reagan is in, suddenly it’s not about stopping the AFL-CIO, but about working within a coalition.”

Conservatives argued among themselves about how to cut taxes—never an easy thing to do in the complicated U.S. tax code. And, of course, cutting taxes contributed to the national deficit. That made some business leaders panic, Waterhouse says. “They’re thinking instability and rampant inflation. By the 80s, there’s more division than there is unity.” Conservative disagreement about taxes, he says, was a large part of the reason why President Bush didn’t have enough support to defeat Bill Clinton in 1992.

More than 20 years later, could a coalition of business interests change the political picture again? It could happen, Waterhouse says. If small and mid-sized businesses came together to protest having to pay for employees’ health insurance, for example, he thinks they might have an effect. “But owners of small companies spend all of their time keeping their businesses going,” he says—not engaging in political activism.

For Waterhouse, who wasn’t born yet when the period he studies began, Lobbying America is a different look at a time that many living scholars remember quite well. “I have no lived memory of any of this,” he says. “I may have picked things up about the 70s, but I’ve also challenged those very things—and that’s what historians are supposed to do. There’s something about going back to historical documents—it gives you a different perspective than people have going about their daily lives.”