Things can get hectic this time of year on a college campus. The big push to the end of the semester demands an intense focus. In these moments, it’s important to take a minute to stop and look around for a fresh perspective. In that spirit, Endeavors is pleased to offer a new look at some of the most popular spots for research in the area. The photography in this photo essay was created using a technique called macro photography, which magnifies the subject to greater-than-life size.

Joel Kingsolver Lab

As Katherine Malinski, a UNC-Chapel Hill PhD student studying evolutionary biology, moves a tobacco hawk moth from its enclosure to a desktop to be photographed, the insect barely moves. In the wild, this moth would much more difficult to photograph because they just can’t sit still, according to Malinski. The current subject, though, was bred here at Carolina and is much more docile.

The tobacco hawk moth is the subject of research from the Kingsolver lab. (photo by Andrew Russell)

Joel Kingsolver’s evolutionary biology lab conducts research on how plants and insects react to changes in their environment. Using moths and butterflies, they study managed ecosystems and invasive species and how they relate to climate change.

One project investigates how the Devil’s Claw — an invasive plant found in the southeastern U.S. — affects Manduca sexta (hornworm) numbers over the past century. While hornworm populations lay eggs and feed on Devil’s Claw, research shows that their rates of larval growth, development, and survival on the plants are lower than hornworms living on other, more common host plants — especially at lower temperatures.

The research demonstrates that while these hornworm populations lay eggs and feed on Devil’s Claw, their rates of larval growth, development, and survival on the plant are less than those on other, more common host plants. As a result, the utilization of this novel host plant by hornworm populations in this area has been made easier by warmer summer temperatures and escape from natural adversaries.

Additionally, the Kingsolver lab does a lot of outreach.

They have created a community service project to teach elementary school students about ectotherms’ thermal performance. Children chart the data they get as they assess the body temperatures and feeding rates of Manduca sexta caterpillars kept in a hot environment (on hot packs) or in a cold one (on ice). Students gain knowledge of the scientific process, charting, and analyzing data, as well as the distinction between ectotherms and endotherms.

Most recently, the lab and the North Carolina Botanical Garden in Chapel Hill have teamed up on the Mason Farm Butterfly Project. Researchers are observing butterflies at Mason Farm Biological Reserve — where more than 100 different species have been seen — to keep tabs on species abundances and flight schedules.

Additionally, Kingsolver uses podcasting as a technique to assist students in exploring evolution principles as well. In his evolution course for non-majors, Evolution and Life, students learn to do research and create podcasts on evolutionary subjects in cooperation with the Education and Outreach team at the National Evolutionary Synthesis Center. Podcasts created by students are a significant component of this course.

Wilson Library

For its 9 millionth volume, University Libraries recently acquired a truly unique item: a collection of 900 woodcut printing blocks dating from 1626 to 1850. Produced by the Sacra Congregatio de Propaganda Fide press, the blocks serve as an incredible celebration of books and provide insight into the history of printing technology, making them incredibly valuable to researchers across various fields.

The Sacra Congregatio de Propaganda Fide press, the publishing arm of the Catholic church, created 900 woodcut printing blocks between the years 1626 and 1850 for the purpose of providing publications pertaining to Catholic tradition and faith. (photo by Andrew Russell)

Since its establishment in 1622, Sacra Congregatio de Propaganda Fide (otherwise known as Congregation for Evangelization of Peoples) has been responsible for producing materials relating to the Catholic faith and tradition. The congregation has supported missionaries in their efforts to spread Christianity throughout different cultures and regions around the world. These publications explain critical concepts of Catholicism, offer guides for missionaries working in foreign lands, and provide resources for priests learning new languages and cultures.

A block covered with printer’s waste, pocked with holes made by bookworms. (photo by Andrew Russell)

For art history scholars, the blocks offer value as a resource for studying iconography in books and in understanding the production of woodcuts used to produce illustrations or art prints. And finally, the woodblocks themselves provide insight into how information was circulated during a time when books were the primary means of communication. This is valuable for researchers to understand how people exchanged ideas in the past.

Each block is wrapped in “printer’s waste,” spare paper that might contain mistakes or be left over from another print job. These wrappings can provide clues as to when and how each block was created. Together, they form an archive that tells a story of its own, providing clues to when they were created and under what circumstances.

A close up of a woodcut printing block. (photo by Andrew Russell)

The library acquired the blocks thanks to funding from the John Wesley and Anna Hodgin Hanes Foundation and the Whitaker Library Foundation.

A piece of printer’s waste shows the image carved onto one of the blocks. (photo by Andrew Russell)

Founded in 1960, the Whitaker Library Fund has been instrumental in expanding the University Libraries’ collection of English and American literature and continental European books and manuscripts.

This latest gift from the Hanes family continues a tradition unique to Carolina beginning in 1929, when the foundation’s funding helped establish Carolina’s Rare Book Collection. They have continued this tradition through their foundation, with the acquisition of every milestone millionth volume.

North Carolina Botanical Garden

While walking through the North Carolina Botanical Garden (NCBG), it’s easy to find carnivorous plants. Just follow the kids. On the weekend, it’s common to see groups of children gathered around a planter, staring intently, hoping to witness a poor hapless insect become lunch for the many pitcher plants and Venus flytraps that populate the garden. NCBG’s mission is to research, catalog, and promote the native plant species of North Carolina — and entertaining kids is a bonus.

An NCBG visitor fan favorite: the Venus flytrap. (photo by Andrew Russell)

The Venus flytrap is a great illustration of the NCBG fulfilling that mission. The plant, only found in a 90-mile inland radius surrounding Wilmington, is a candidate for the federal endangered species list. Its researchers use genetic testing and seed banking to preserve these carnivorous marvels as wild populations decline because of poaching and habitat destruction.

Venus flytraps are only native to a small area of the coastal plain in North and South Carolina. (photo by Andrew Russell)

The Coker Arboretum represents the first steps toward what would become the NCBG. It was established in 1903 as a teaching collection of trees and shrubs planted by William Chambers Coker, Carolina’s first professor of botany. Coker and his protégé, Henry Roland Totten, sought to construct a more comprehensive botanical garden south of the main campus beginning in the late 1920s.

After some plantings occurred in the 1930s and ’40s, UNC-Chapel Hill trustees committed 70 forested acres to the establishment of a botanical garden in 1952. William Lanier Hunt, a horticulturist and former student of Coker and Totten, gave 103 acres of magnificent creek canyon and rhododendron bluffs to this tract.

The Virginia saltmarsh mallow is a coarse, hairy perennial often found in Louisiana. (photo by Andrew Russell)

The nature paths, the garden’s first accessible feature, debuted on Arbor Day in 1966 and, today, include 165 acres of uncultivated woodlands with groves that are over 200 years old. The garden’s volunteer program was launched, the first regular personnel were hired, and the first demonstration gardens were built in 1971. Additionally, in 1991, the garden acquired Paul Green’s cabin, where the famous North Carolina playwright found inspiration and calm.

A Virginia saltmarsh mallow. (photo by Andrew Russell)

The North Carolina Botanical Garden’s primary exhibition space is home to eight significant collections: the Southeastern Habitat Collection, which includes the Mountain Collection, the Sandhills Collection, and the Coastal Plain Collection; the Plant Families Garden; the Carnivorous Plant Collection; the Rare Plant Collection; the Southeastern Fern Collection; Native Perennial Borders; the Aquatic Collection; and the Mercer Reeves Hubbard Herb Garden.

Today, the NCBG has become a hub for the research, exhibition, interpretation, and protection of plants and their natural habitats. Through its initiatives for reintroduction, plant rescue, conservation through propagation, management of natural areas, and promotion of native plants, the botanical garden is one of the top conservation gardens in the country.

Southern Folklife Collection

Walking through the fourth floor of Wilson Library, home to the Southern Folklife Collection (SFC), is like a history lesson in southern culture ephemera. Amazing relics of southern life can be found in every corner. A Dolly Parton standee sits next to an Edison Ediphone, one of the earliest recording devices. Down the hall, a record collection belonging to famed Atlantic Records producer Jerry Wexler lines the shelves behind a hand-painted flaming recliner from the cover of Southern Culture on the Skids’ 1997 “Plastic Seat Sweat” album.

Carolina legend Andy Griffith donated a collection of his papers and personal items, including his signature Martin D-18 guitar to the Southern Folklife Collection. (photo by Andrew Russell)

The SFC is rich in materials documenting the emergence of old-time, country-western, bluegrass, blues, folk, gospel, rock-and-roll, Cajun, and zydeco music. It contains over 300,000 sound recordings, 3,000 video recordings, and eight million feet of motion picture film, as well as tens of thousands of photographs, song folios, posters, manuscripts, books, serials, research files, and ephemera. It’s a hub for various archival holdings for the study of Southern American folk music and popular culture.

The collection traces its roots back to 1940, when the curriculum in folklore at UNC-Chapel Hill was established, making it one of the oldest graduate programs of its kind in the country. In 1968, the department established the UNC Folklore Archives, and much of its holdings were donated by department faculty. The goal was to collect, preserve, and disseminate important pieces that represent southern life.

A wax cylinder containing the song, “All the Beckoning Hands,” is part of the Southern Folklife Collection. (photo by Andrew Russell)

In honor of a young Australian record collector, the John Edwards Memorial Foundation was established in California in 1962 as an archive and research facility. His outstanding collection of American country music records, together with a wealth of correspondence and other study resources, were supplemented by additions from his American friends and colleagues after Edwards’ unexpected death in 1960. In the late 1980s, UNC-Chapel Hill purchased the collection from the University of California, Los Angeles, and combined it with the Folklore Archive, forming the SFC.

A wax cylinder. (photo by Andrew Russell)

Over the years, the SFC’s reputation has grown along with its holdings. The sheer scope of the collection makes it an important resource for those interested in the traditional music, art, and culture of the American South. And that has brought donations from some notable people, including Carolina legend Andy Griffith, who donated some of his papers and personal items, including his signature Martin D-18 guitar. More recently, longtime Jerry Garcia collaborator and mandolin virtuoso, David Grisman, bequeathed his personal archive to the SFC.

Morehead Planetarium and Science Center

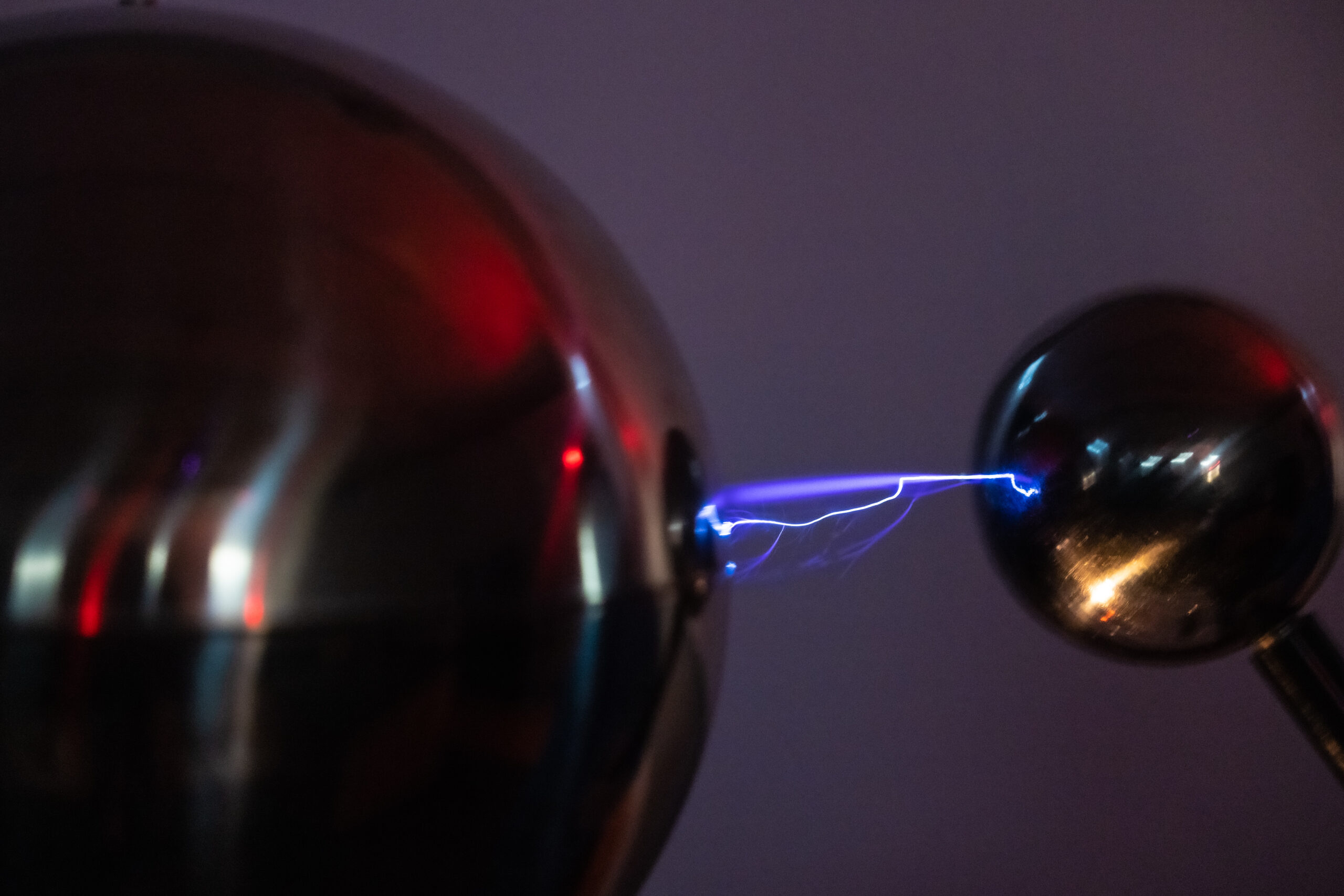

As the lights go down in one of the classrooms at Morehead Planetarium and Science Center, a low hum starts to emanate from a basketball-sized silver ball mounted on a stand on the desk at the front of the classroom. It’s called a Van Der Graaf generator, and it’s designed to generate static electricity.

A device called a Van Der Graaf generator generates static electricity to create a tiny but powerful spark at Morehead Planetarium. (photo by Andrew Russell)

Tara Capel, an educator with the planetarium, holds a stick attached to a smaller silver ball, and a loud pop rings out. The audience, mostly children, collectively gasp. Another pop is heard, and then another, and finally, with the last pop, a spark of electricity arcs — and the kids explode with cheers. Generating that kind of engagement with science is what Morehead Planetarium does best, even with astronauts.

From 1959 to 1975, the planetarium provided a critical training ground for practicing celestial navigation for astronauts who participated in the Mercury, Gemini, Apollo, Skylab, and Apollo-Soyuz Test Project programs. Morehead technicians created streamlined duplicates of flight modules and tools, frequently out of cardboard or plywood. To facilitate pitch and yaw adjustments, a prototype replicating the Gemini capsule was installed on a barber chair. The planetarium still has a few of these items on exhibit.

Tara Capel shows off the Van Der Graaf generator at the Morehead Planetarium. (photo by Andrew Russell)

On May 10, 1949, the planetarium opened after a 17-month development process. It was built by UNC-Chapel Hill alumnus John Motley Morehead III at a cost of $3 million (about $30 million in today’s money), making it the most expensive building in North Carolina at the time. It was the sixth planetarium to be erected in the United States and the first in the South.

Back then, Zeiss, the German lens company that manufactured planetarium projectors, had lost much of its manufacturing capacity during World War II. Morehead was forced to travel to Sweden, to purchase a new Zeiss Model II projector. The first show in the planetarium was appropriately titled, “Let There Be Light.”

By the planetarium’s 50th anniversary in 1999, the theater had welcomed more than 5 million visitors. The next year, to reflect the facility’s expanded mission, it was renamed the Morehead Planetarium and Science Center. Now, in addition to serving as a window to the stars, it serves as a gateway to all the sciences, introducing young viewers to topics like genetics, virtual reality, concussion research, and nanotechnology.

Morehead expanded again in 2010 with the advent of the North Carolina Science Festival, the first statewide celebration of science in the nation. The annual month-long festival includes hundreds of events around North Carolina to showcase the educational, cultural, and economic influence of science. Events include interactive activities, lectures, lab tours, displays, and performances.

Even as it has branched out into other fields, Morehead has remained faithful to its origins as a preeminent planetarium. This summer, its projector was upgraded to a brand-new 4K laser projection system, providing visitors with a crisper view of the night sky than has ever been possible in Chapel Hill. With the aid of this new equipment, viewers can see a wider field of stars with six times the contrast and nearly seven times the brightness of our prior projection technology.