When you were a child, what was your response to this question: “What do you want to be when you grow up?”

From the ages of 4 to 7, I would tell anyone who would listen that I was going to be a sea turtle when I grew up. I’m not sure exactly when someone broke the news that being this wasn’t the most realistic career goal, but along the way I settled on marine scientist. Though if anyone reading this has any ideas for the former, I’m still listening…

RESEARCH IN 5 WORDS:

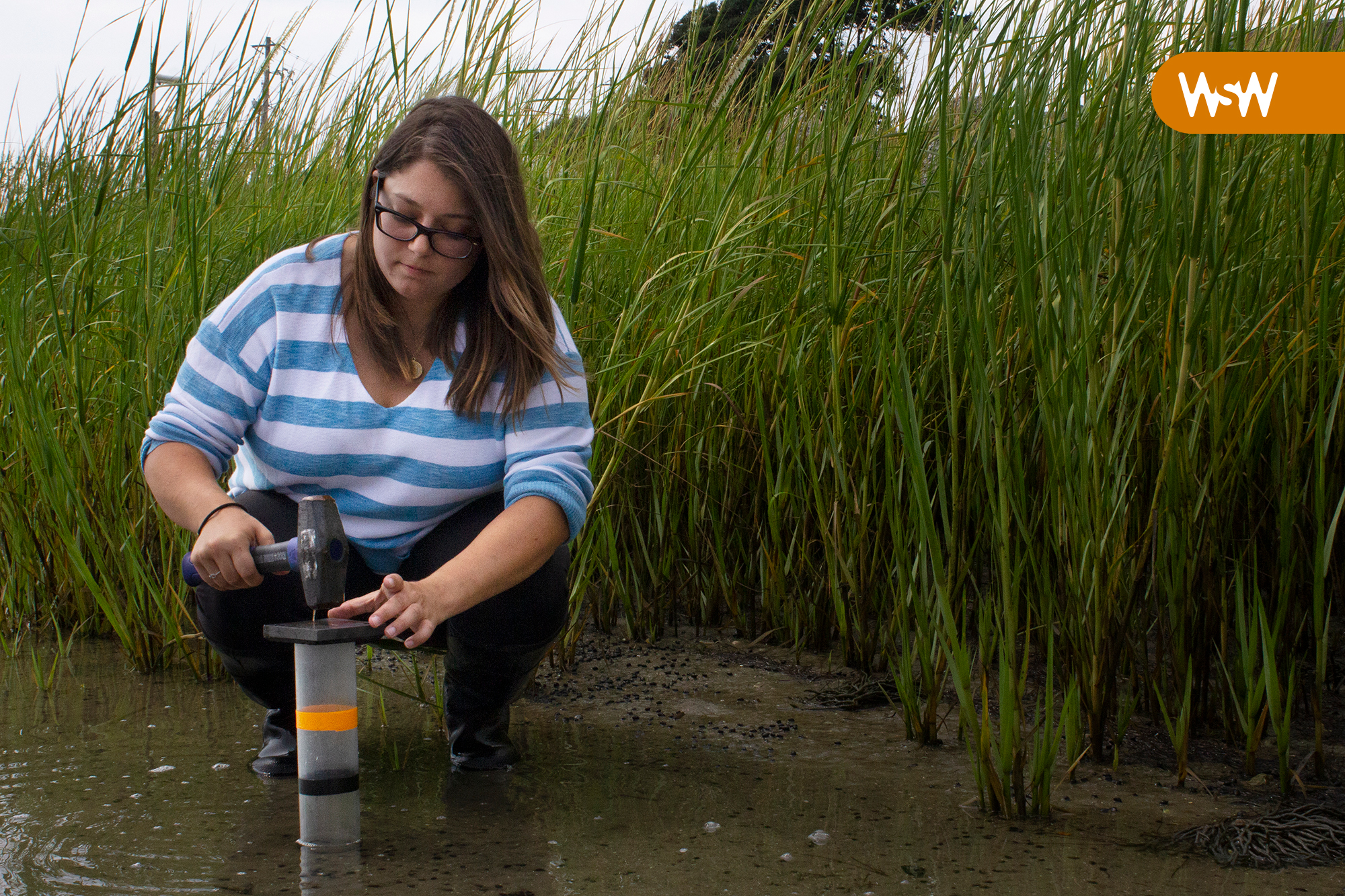

“Studying mud to understand nutrients.”

Share the pivotal moment in your life that helped you choose your field of study.

When I was in elementary school, a family friend was the vet at the North Carolina Aquarium on Roanoke Island, and took my family on a tour behind the scenes of all their exhibits and their sea turtle rehabilitation area. From that moment on, there was no question that I wanted to make loving the ocean my career. I went into college with that same mindset, but I didn’t really know what exactly about the ocean I wanted to study. I was fortunate that the first course I took during my undergraduate studies was “Intro to Oceanography,” taught by Wally Fulweiler, a marine biogeochemist. Not only did this expose me to a lab full of strong women in science, but it was also the deciding factor in me pursuing my graduate studies in marine biogeochemistry.

Tell us about a time you encountered a tricky problem. How did you handle it and what did you learn from it?

In the field this past summer, I found myself in a few tricky situations that we thought would go smoothly, but proved more difficult once we actually got out into the marsh. One of the big ones is that my furthest field site has limited accessibility from land to the area we needed to sample in, but is also so shallow that it becomes difficult to guide a boat through. We turned to a locally run eco tour company and decided to partner with them as they had both the equipment and the knowledge of the shallow channels to successfully navigate to our sampling locations. This had the added benefit of educating them about the research, which takes place in a system they already have a vested interest in protecting. You have to willing to be flexible and adapt because things are never going to go as smoothly in the field as they may on paper.

What are your passions outside of research?

In general, I love pretty much anything outside. I started surfing when I was young and that was one of the main things that built my love of the ocean and remains one of my biggest passions, so I try to get into the water as much as possible. It’s important for me to have passions outside of science because it allows me opportunities to step back from my work and put everything in perspective.