Eight-year-old Isis Trujillo and her younger brother, Ricardo, sit on the floor of their home in Mexico, sorting letters from all over the world. They separate them into piles: one for Asia, one for Europe, and one for North America. These weren’t pen pal letters from a class project — they were requests for a research publication.

The year was 1994. Trujillo’s father had just completed his PhD in chemistry and requests were pouring in for a research manuscript detailing the findings from his thesis project. Before scientists could readily share their research on the internet, colleagues would contact the lead author by letter. Receiving multiple letters from across the globe was like receiving an award. It was recognition of novel, interesting, and breakthrough science. Trujillo recalls the experience as one of the most inspiring moments in her life.

“I knew that one day I wanted to do something like that,” she says.

Growing up with a chemist for a father and an educator for a mother, Trujillo was encouraged to explore and express creativity from a young age. They also nurtured her passion for science alongside her grandmother, a local midwife whose home was always stocked with natural remedies, such as local plants, to treat ailments.

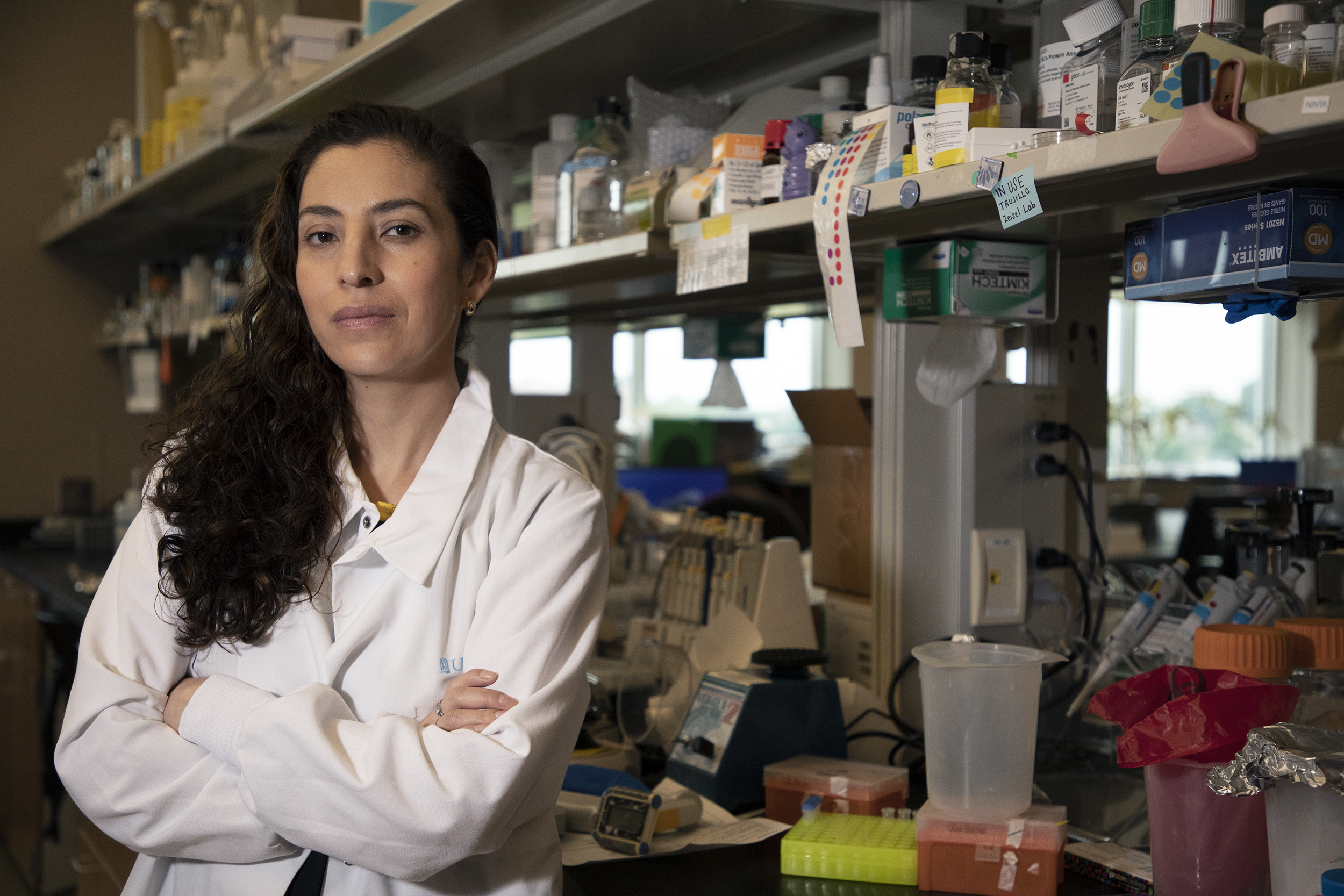

Now an assistant professor at the UNC Nutrition Research Institute (NRI), Trujillo is forging her own way as a prominent research scientist to understand how choline, an essential nutrient, improves the way we think and behave before we are even born. What’s more, she’s now leading the lab of former NRI Director Steven Zeisel upon his recent retirement — and is working to make it her own.

Feeding a growing brain

The critical role of choline in human health begins in the womb, attained through a mother’s diet of foods such as eggs, salmon, milk, and liver. Low choline intake during pregnancy has lasting negative effects on a child’s attention, memory, and ability to problem-solve. But how can a single nutrient create such long-lasting impacts in the relatively short amount of time it takes to form a brain?

The adult brain consists of a community of neurons with specialized functions that work together to write and deliver messages that help us think, feel, and move. Although neurons can differ in their responsibilities and actions, each one arises from a common population of ancestor cells called neural progenitors.

The brain begins as a small pool of progenitor cells that divide and generate copies of themselves, which then undergo maturation to become neurons. This growth strategy doubles the number of progenitor cells that will become neurons with each cell division, allowing the fetal brain to expand at a rapid rate. Toward the end of pregnancy, and after birth, neural progenitor activity slows as the brain devotes more energy toward fine-tuning cognitive functions and less energy on growth.

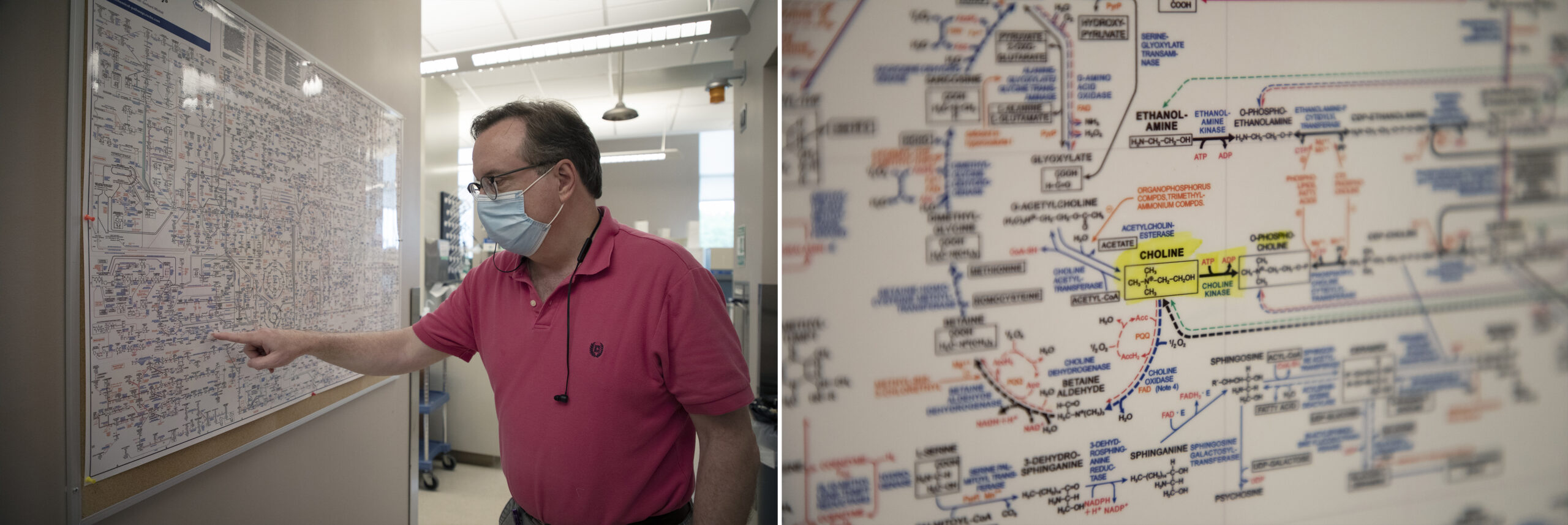

Walter Friday, a research technician in the Trujillo Lab, points out choline on a chart of metabolic pathways that hangs in the lab. “I bet you didn’t know that your body was doing all of this all the time,” he says. (photos by Alyssa LaFaro)

As a postdoctoral researcher, Trujillo found that mice with mothers that were fed a low choline diet during pregnancy have a smaller pool of neural progenitor cells. This depletion is caused by increased abundance of a micro-RNA, a small molecule that prevents certain genes from being expressed. In the case of low choline, the micro-RNA inhibits the expression of a gene involved in neural progenitor growth and division, resulting in a smaller brain with fewer neurons.

“What we eat actually modifies our genes and that, for me, is very interesting. That is my passion,” Trujillo says.

Having established how choline affects normal brain growth, she is now exploring its benefits when brain development is impaired.

One of the major barriers to treating neurodevelopmental disabilities is that diagnosis usually does not occur until after the brain is partially, or even fully, developed. At this point, the symptoms can be treated, but the underlying structural and functional changes in the brain remain. Rett syndrome, a severe neurodevelopment disability that primarily affects girls, is particularly affected by these hurdles.

For the first six to 18 months of life, a child with Rett syndrome develops normally, eating, growing, and interacting like most infants. Early symptoms are often characterized as missed milestones. Parents may notice their child isn’t crawling or self-feeding like other infants. Following what seems to be a simple developmental delay is a period of rapid regression, including loss of motor skills, mental deterioration, and social withdrawal.

Trujillo became an assistant professor at NRI in January 2021 and began the transition to take over the Zeisel Lab upon his retirement in May 2021. Zeisel will continue to work as a professor of nutrition and pediatrics and as a consultant for the lab. (photo by Alyssa LaFaro)

Researchers at Duke University showed that supplementing choline shortly after birth improves brain development in Rett syndrome by rescuing the growth of neuron dendrites — branch-like structures that act as a neuron’s fingers, allowing it to grasp onto and receive signals from its neighbor neurons. By correcting neuron communication, choline improves some anxiety-like behaviors in mice that have Rett syndrome features.

Trujillo argues that even greater improvements may occur with earlier intervention.

“I think we should be looking at Rett syndrome at early stages, because oftentimes we are looking at the end point, and when we realize it is Rett syndrome, it is too late,” she says.

Trujillo hopes that supplementing choline during pregnancy will create a ripple effect, improving the function of neural progenitors and the neurons they produce.

“If I see that the neural progenitors are affected, then by supplementing choline in the disease state, I will probably fix some of those issues before the cell becomes a mature neuron.”

Carrying on the choline legacy

Trujillo is well-equipped with the knowledge and experience to tackle these questions, having been trained by the leading expert on choline, Steven Zeisel. Zeisel was the first to demonstrate the human requirement for choline and has made numerous contributions toward understanding factors, including genetics, that modify these requirements. After 13 years as director of the Nutrition Research Institute, Zeisel is stepping down, but not without making sure the field of choline research is left in good hands.

But Trujillo is not simply picking up where Zeisel left off. Through her postdoctoral training, she has carved her own niche in choline research.

“Isis has made some outstanding discoveries that are very important and will be a great basis for a young faculty member to build a career and move up the ladder at the University of North Carolina,” Zeisel says.

As she continues investigating the critical role of choline in the brain, Trujillo recognizes how much remains unknown.

“Choline is having all these beneficial effects for neurological diseases at any stage, and I don’t think it’s through the same mechanism. I think it depends on the context,” she says. “The fact that a nutrient can help in so many aspects makes me think we can study choline for another 20 years at least.”

Zeisel is confident Trujillo will continue pursuing her research with the resilience she has shown since starting at NRI in 2015.

“Isis kept learning and using that new knowledge to improve the way she asked her research questions,” Zeisel says. “Her work shows one of the earliest times we have seen a nutrient modify a micro-RNA, and that micro-RNA exerts an effect on the brain. That explains quite well why choline is so important for brain development.”

He also believes Trujillo will be an excellent mentor for the next generation of scientists.

“Not only does Isis have a science skill set, but she has an interpersonal skill set that a professor needs to be successful.”

Zeisel has helped shape Trujillo’s mentoring philosophy. While working on her micro-RNA project, Trujillo hit a research roadblock. Unsure of the next steps, she expressed her concerns with Zeisel.

“I told him I don’t know if this micro-RNA is regulated at the transcriptional level or at subsequent steps,” she says.

Instead of telling Trujillo what she could do, Zeisel asked her how she would prove it. So, she provided him with a list of possible experiments to test her hypothesis.

“He said: ‘Okay, test it. And if it doesn’t work, what are you going to do next?’” she recounts. “He is not the type of principal investigator to tell you exactly what to do. He focuses on the big picture and actually lets you think about how to do [the experiments].”

Trujillo hopes to give her students and trainees the intellectual and creative freedom she experienced during her postdoctoral training and looks forward to contributing to the supportive and collaborative environment at UNC.

Trujillo and Friday (right) discuss an experiment with PhD student Evan Paules (center). Paules studies the effects of choline-sensitive microRNA during brain development and in the adult liver. (photo by Alyssa LaFaro)

Trujillo is thankful she finds a similar level of support back home. As a child, her parents encouraged her to choose her own career path.

“Of course, my parents say they knew from day one that I was going to do research,” she says. “They are sad that I’m far from home, but at the same time they are glad to see me happy.”

Although being far from home is challenging, Trujillo’s experience at NRI has yielded some of her greatest accomplishments.

“Having this opportunity for me was huge. And once I got here, the trust and the confidence that the Zeisel Lab gave me allowed me to grow and has been one of the best experiences I have ever had,” she says. “I am most proud of myself for coming to NRI.”