PhD student Lewis Naisbett-Jones and research technician Creed Branham have an office view most can only dream of. Cruising along the shore of Harkers Island, N.C., they head toward Cape Lookout — a barrier island accessible only by boat. On the way, they pass wild horses grazing and extravagant sailboats bobbing along on blue water.

While it may be an idyllic setting, their work is far from glamorous. The two are searching for acoustic tag receivers placed in the water last year. Once identified, they use a hooked pole to haul the receivers onboard and scrub them of biofouling — the grimy buildup of organisms like barnacles, algae, and bacteria. It’s not pretty, but it’s a monthly chore necessary to keep Naisbett-Jones’ research alive.

The pair are in their second year of tracking the migration of sheepshead — a small coastal fish easily identified by its gray-to-black and white banding and human-like teeth. During warm months, sheepshead can be found among inshore habitats like rock pilings, piers, and reefs. In the cooler months, around October or November, they migrate offshore to reproduce. But, when exactly they leave, where they go, and what habitats they prefer for spawning are largely unknown.

“I’m really interested in the mystery that revolves around fishes,” Naisbett-Jones says. “Fish are the most diverse vertebrate group on the planet and yet they’re probably the group we know the least about in terms of their movement and migration. I love the problem-solving aspect of trying to answer some of these questions.”

Acoustic tag data will tell Naisbett-Jones when and from what point the fish are leaving their inshore habitats. Satellite telemetry comes in next, providing information about where the sheepshead go to spawn offshore. The North Carolina Division of Marine Fisheries is particularly interested in this data in order to effectively manage the species.

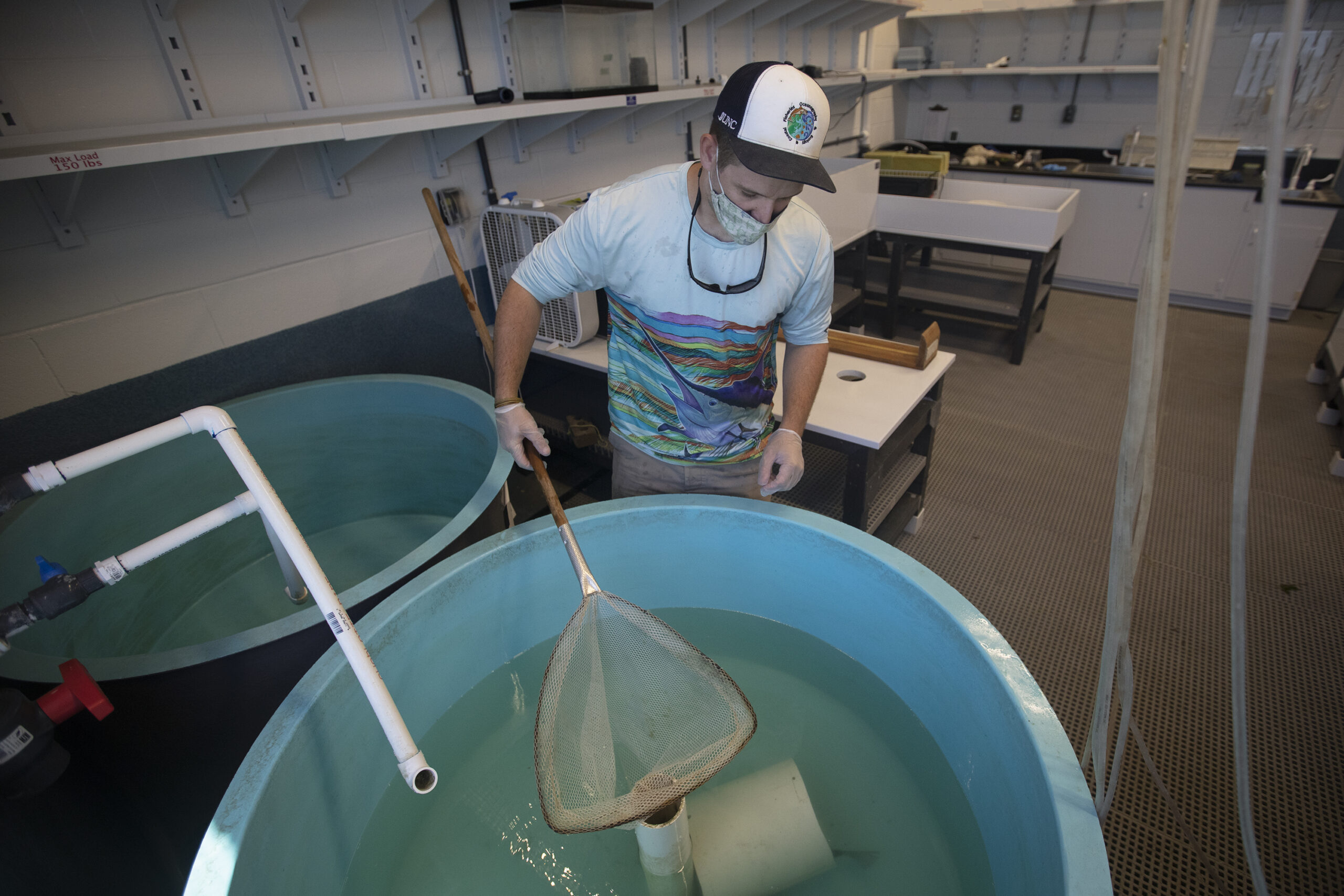

Naisbett-Jones works to net a sheepshead from a tank in in order to fit it with an acoustic tag. Once released into the wild, receivers placed at the mouths of inlets and estuaries can detect these acoustic “pings” when the fish is nearby. While dependent on factors like wave action and boat traffic, a receiver can record a tag up to a kilometer away.

Naisbett-Jones works to net a sheepshead from a tank in in order to fit it with an acoustic tag. Once released into the wild, receivers placed at the mouths of inlets and estuaries can detect these acoustic “pings” when the fish is nearby. While dependent on factors like wave action and boat traffic, a receiver can record a tag up to a kilometer away.

When an acoustic receiver picks up a signal, the tag number, date, and time of day is noted. This provides insight into when and from what specific location the fish is leaving its inshore habitat.

When an acoustic receiver picks up a signal, the tag number, date, and time of day is noted. This provides insight into when and from what specific location the fish is leaving its inshore habitat.

Naisbett-Jones attaches a pop-up satellite tag to a large female sheepshead. The tag is programmed to release and float to the surface in April — when the fish are thought to spawn. Once surfaced, the tag can send water temperature and location data to a satellite, at which point Naisbett-Jones can download that information. “That information is important because it can tell us where they are and what type of habitat the fish utilize for spawning,” he says.

Naisbett-Jones attaches a pop-up satellite tag to a large female sheepshead. The tag is programmed to release and float to the surface in April — when the fish are thought to spawn. Once surfaced, the tag can send water temperature and location data to a satellite, at which point Naisbett-Jones can download that information. “That information is important because it can tell us where they are and what type of habitat the fish utilize for spawning,” he says.

Naisbett-Jones holds a satellite tag used in his research. For years, these tags were used only to track large terrestrial or marine species. Recently, though, they have been made smaller and at lower cost — going from about $5,000 to $1,200 — offering an opportunity for researchers to collect data on smaller species.

Naisbett-Jones holds a satellite tag used in his research. For years, these tags were used only to track large terrestrial or marine species. Recently, though, they have been made smaller and at lower cost — going from about $5,000 to $1,200 — offering an opportunity for researchers to collect data on smaller species.

Naisbett-Jones releases a sheepshead at the pier next to the UNC Institute of Marine Sciences. Last year, he tagged 20 fish with acoustic tags and 25 with satellite tags. From the satellite-tagged group, data was obtained for 17 of the 25 — a success in terms of satellite-tagging standards. He expects to tag the same amount this year.

Naisbett-Jones releases a sheepshead at the pier next to the UNC Institute of Marine Sciences. Last year, he tagged 20 fish with acoustic tags and 25 with satellite tags. From the satellite-tagged group, data was obtained for 17 of the 25 — a success in terms of satellite-tagging standards. He expects to tag the same amount this year.

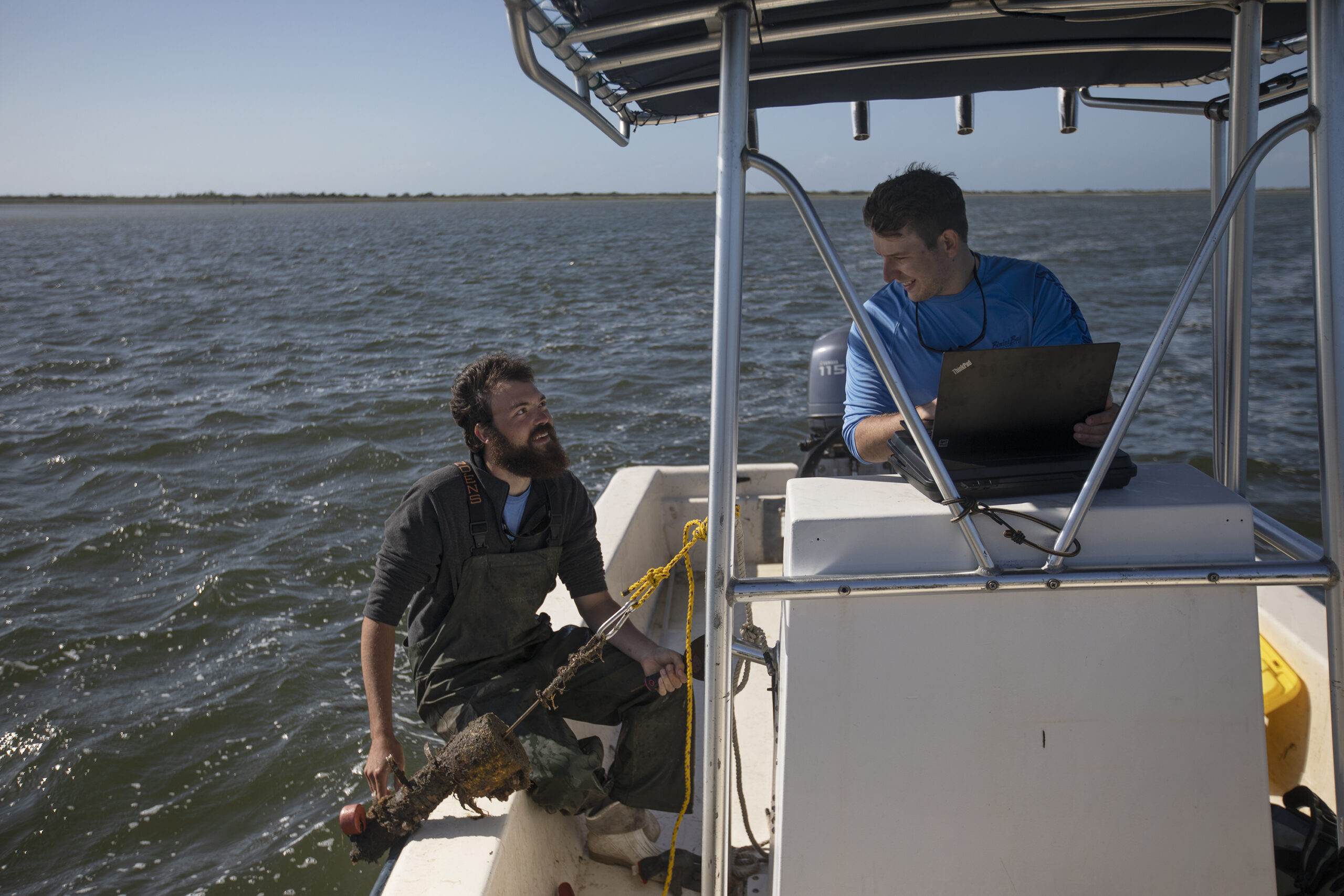

Naisbett-Jones downloads data from an acoustic receiver as Branham scrubs biofouling off the device. While the duo maintain just four acoustic receivers, they benefit from receivers deployed by other labs for various research projects. “It’s this great collaborative effort where everybody shares their data. So, in reality, we maintain four receivers, but we have access to data from over 50 in that area.”

Naisbett-Jones downloads data from an acoustic receiver as Branham scrubs biofouling off the device. While the duo maintain just four acoustic receivers, they benefit from receivers deployed by other labs for various research projects. “It’s this great collaborative effort where everybody shares their data. So, in reality, we maintain four receivers, but we have access to data from over 50 in that area.”

Naisbett-Jones cleans an acoustic receiver and its attached buoy. Not only does he share data with other researchers in North Carolina, he also benefits from data collected by the Atlantic Coast Telemetry Network — a data-sharing network of researchers using acoustic telemetry all along the coastline.

Naisbett-Jones cleans an acoustic receiver and its attached buoy. Not only does he share data with other researchers in North Carolina, he also benefits from data collected by the Atlantic Coast Telemetry Network — a data-sharing network of researchers using acoustic telemetry all along the coastline.

Naisbett-Jones and Branham deployed acoustic receivers at inlets or estuary mouths, where they expect sheepshead to swim through. “It’s a high likelihood that when the fish head offshore they have to leave through one of these inlets,” Naisbett-Jones explains. “So we kind of created a detection gateway, with receivers at these different locations.”

Naisbett-Jones and Branham deployed acoustic receivers at inlets or estuary mouths, where they expect sheepshead to swim through. “It’s a high likelihood that when the fish head offshore they have to leave through one of these inlets,” Naisbett-Jones explains. “So we kind of created a detection gateway, with receivers at these different locations.”

Tagged sheepshead that migrated offshore last year remained within North Carolina coastal waters — most were located around the continental shelf outside Morehead City, the furthest migrating 27 miles. But, some actually stayed inshore year-round. Naisbett-Jones hopes consistent tracking will provide more insight into the lives of those that make the migration, as well as those that stay inshore. “This is a new and unexpected finding and we’re not entirely sure why this is,” he says. “It’s possible that they don’t reproduce every year, or maybe some spawn inshore. We’re hoping to shed some more light on this finding with our tagging efforts this year.”

Tagged sheepshead that migrated offshore last year remained within North Carolina coastal waters — most were located around the continental shelf outside Morehead City, the furthest migrating 27 miles. But, some actually stayed inshore year-round. Naisbett-Jones hopes consistent tracking will provide more insight into the lives of those that make the migration, as well as those that stay inshore. “This is a new and unexpected finding and we’re not entirely sure why this is,” he says. “It’s possible that they don’t reproduce every year, or maybe some spawn inshore. We’re hoping to shed some more light on this finding with our tagging efforts this year.”