Tucked between a few trees along US-17 in Gloucester, Virginia, an array of tents and A-frame stands are spread out across the lawn of the historic Woodville School. Kneeling over a strategically dug square, Colleen Betti scrapes her trowel across the top layer of exposed dirt, her eyes scanning the surface for any variation in soil color — or the tip of a piece of protruding glass, coal, slate, or if she’s lucky, an ornate bead or the remains of a pencil.

Virginia may not be the first place that comes to mind as a hot-spot for archaeology, but Betti, a UNC-Chapel Hill PhD student, has been excavating here for years. She is interested in how the daily lives of children are preserved in the archaeological record, and schools provide a great opportunity to find out.

“I think children are missing from a lot of archaeological and historical interpretations,” Betti explains. “These schools are great sites to bring the community into archaeology and talk about the history of a place with people from all walks of life because everyone went to school at some point.”

This site is of particular interest to Betti because it is home to not just one but two historically African American schools, providing an important glimpse of what life was like from the late-1800s to the mid-1900s. Both called the Woodville School, only one still stands. Betti is searching for the archaeological remains of the other, built in 1885 and located somewhere on the same plot of land.

In late August, the schoolyards and community knowledge held within the soil were slated to be paved over to create a parking lot so that the Woodville School can be converted into a public museum. That meant the clock was ticking on Betti’s excavation earlier this summer. She put out a call to action — to the UNC archaeology program, to Facebook groups, and to archaeology volunteer pages — inviting anyone interested to come out and help excavate as much of the site as possible before summer’s end.

The building currently standing on the property, the Woodville School, was one of 5,300 Rosenwald Schools built across the American South during the progressive movement of the early 20th century. The Rosenwald Fund was a partnership between Booker T. Washington and Julius Rosenwald, the CEO of Sears Roebuck at the time. If a rural African American community raised as much money as they could to build a schoolhouse, the Rosenwald Fund would provide grants to fill in the gaps.

A student volunteer shakes an A-framed sifter to filter through a layer of excavated soil. They’re looking for artifacts that may reveal more information about the daily life of students who attended the two schools that operated on this plot.

Most of the archaeological evidence that Betti and her team of volunteers found seem to be from the 1885 Woodville School. Coal litters the schoolyard, probably because it was used for heat, and the team has collected 1,500 pounds of it since the excavations began. They also found pieces of slate — evidence of the writing slates commonly used in the classroom.

Zoe Schwandt and Cayla Colclasure note an area of irregular soil color, called a feature, in the unit they are excavating on graph paper. Both third-year anthropology graduate students with concentrations in archaeology, they decided to help Betti with the dig after receiving her email to the department.

Square units of the schoolyard are excavated in layers and carefully documented. A change in soil color typically denotes a different activity occurring or a different time period. The researchers use a standardized way of noting each layer’s color to aid in dating the sediment and artifacts found within it. A student volunteer takes a sample of a soil layer to classify its color using the Munsell Soil Color Chart.

Sifting, digging, standing, and sweating in the summer heat all day is taxing work, but volunteers like Evan Cabral, a senior archaeology major at UNC, were eager to help. Cabral spent two weeks at the field site.

Numerous students of varying levels of experience answered the call to aid in the emergency excavation. “We’ve gotten a great number of students,” Betti says. “Some of them have had a field school and some of them haven’t, but they’ve all picked things up really quickly and have been a huge help.”

Betti has spent three years excavating the Woodville Schools and, so far, has unearthed over 38,000 artifacts. These include pieces of writing tablets, soda bottles (pictured left), and jelly jars. Through consulting photos in the National Archives, Betti discovered that students would drink water from the jelly jars, which explains why she and her team have found so many.

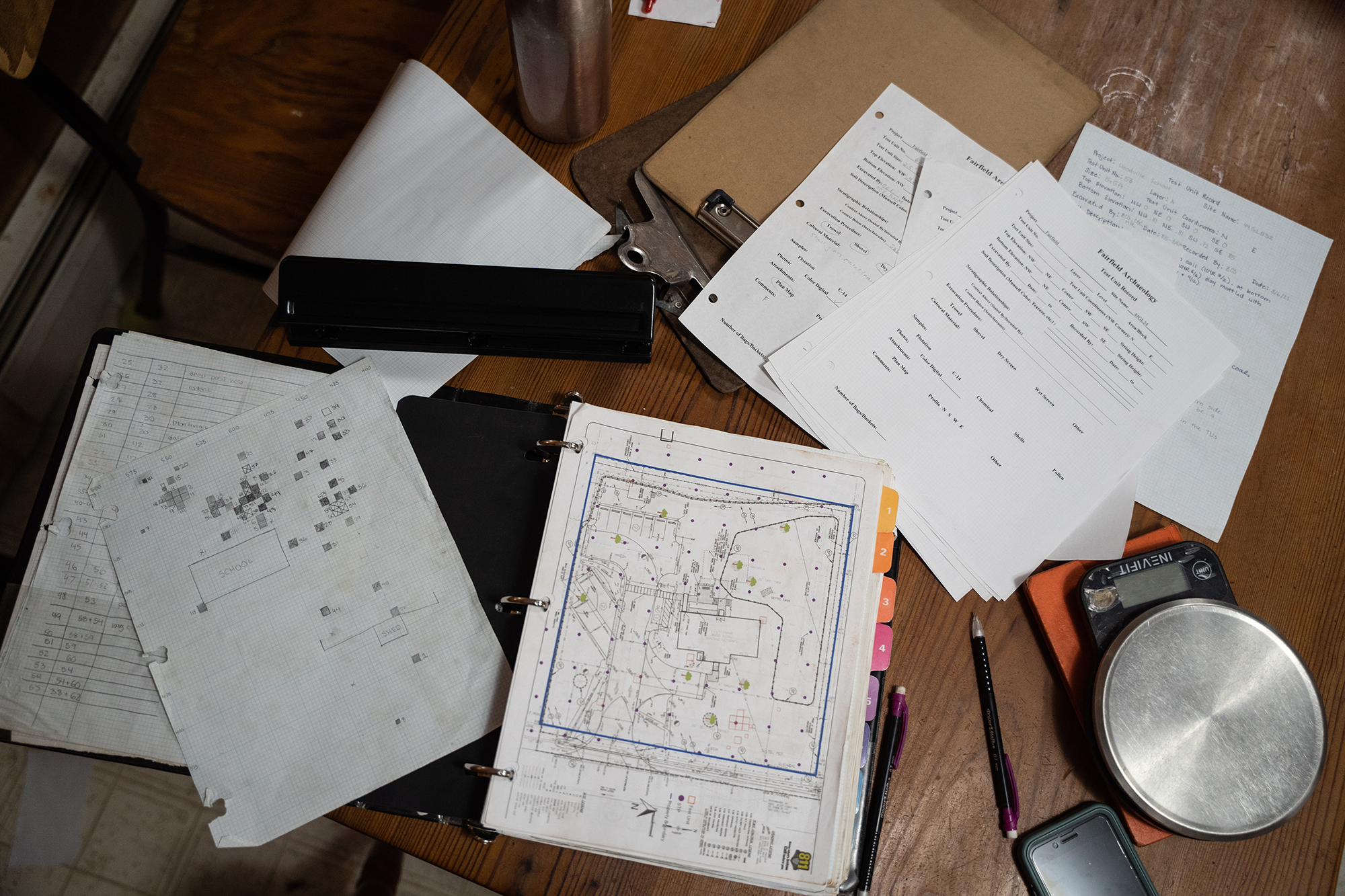

Maintaining detailed notes of the excavation and location at the site where artifacts are found is crucial for archaeologists when reconstructing the narrative of the places where they are digging. Betti has been collaborating with members of the community who have individual or family stories about the schools to help understand what life might have been like for the students who attended them.

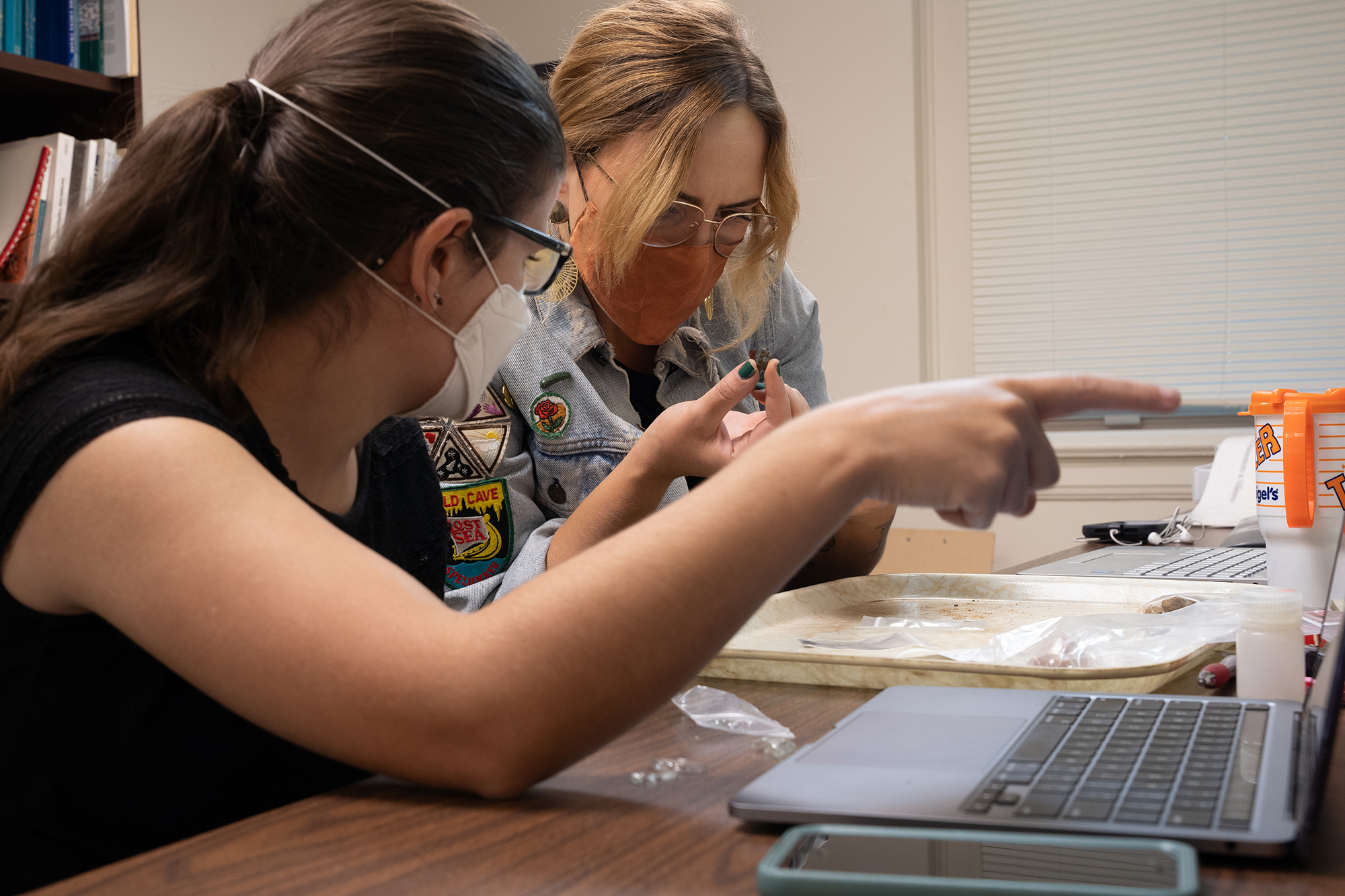

The work doesn’t end in the field. Everything the crew excavated must be processed, photographed, and documented in labs. While some of the processing work is happening at UNC, Betti says most of it is being done by the Fairfield Foundation labs in Virginia. They have yet to meet their fundraising goal to pay the technicians and continue this project. The team is still working to raise these funds, and donations can be made here.

“A lot of the artifacts that we’re excavating will hopefully come here to Woodville and put in sort of a museum display,” Betti says. “So when they’re talking to school groups about what life was like in the schools, we can actually show some of the objects that students were using.”