Reatini first visited the Galapagos in 2015, as part of an undergraduate study-abroad program through USFQ-GAIAS. “I fell in love with the Galápagos as a place, but I also realized there is a lot of research still to be done there,” he says.

As he began to research avenues for conducting research on the islands, Reatini found the Galápagos Science Center, which ultimately led him to pursue his PhD at UNC-Chapel Hill.

Two types of guava are found across the archipelago. The native species is referred to as Galápagos guava (Psidium galapageium), while common guava (Psidium guajava) was introduced by farmers over a century ago. Reatini wants to learn more about how both species are evolving on the islands, and whether or not hybridization is occurring between them.

Reatini inspects a native guava tree at the Galapaguera (tortoise reserve) on San Cristóbal. Because native guava is small and bitter, early 20th century farmers on the islands brought in common guava. “The local birds and tortoises love the native guava, but humans prefer a bigger fruit,” he says.

Reatini cuts into a piece of common guava. While this type of guava is typically found in the highlands of the island (above 300 meters), Reatini was surprised to find this fruit at a lower elevation, around 60 meters.

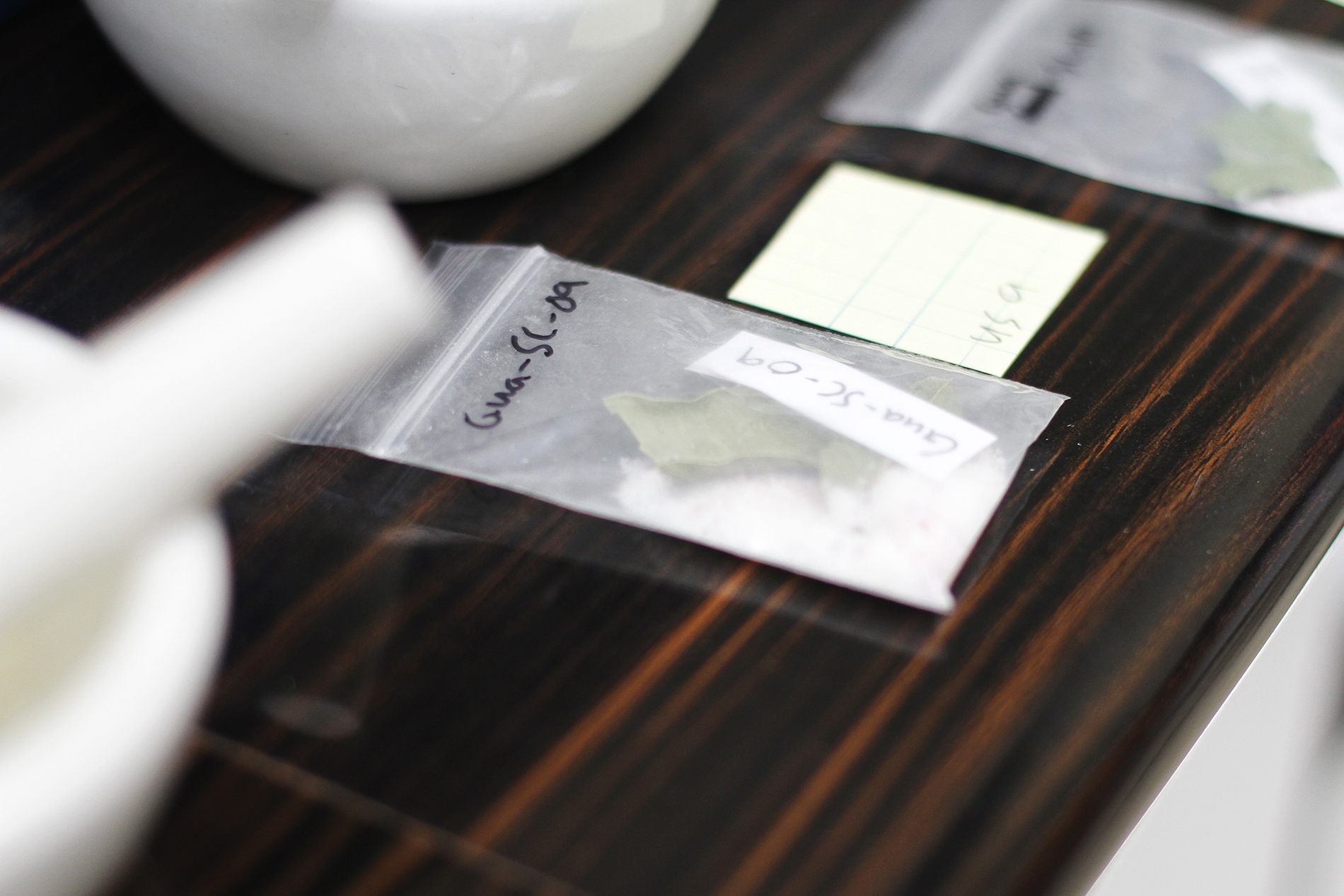

Reatini processes his samples in the terrestrial ecology lab at the Galápagos Science Center on San Cristóbal. During this summer’s field work, he collected 100 samples from three different islands.

Reatini uses a mortar and pestle to grind up guava leaves.

Reatini labels samples by type of guava, location, and number. “All of the islands here are relatively isolated from one another, so they’re like natural laboratories,” he says. “It’s one of the things that makes the Galápagos the perfect place to study evolution — you can observe how these species are evolving independently within each isolated island.”

By grinding the guava into a powder, Reatini can extract DNA from his samples and conduct genomic sequencing. Looking closely at the DNA enables him to search for signals of natural selection, and whether or not the two species are cross-breeding.

The common guava (on the left) produces a bigger, sweeter fruit while the Galápagos guava is smaller and full of large seeds.

Reatini examines a native guava tree at the tortoise reserve on San Cristóbal. “I was surprised to see so many native guava trees in this location, but since the tortoises eat the guava and spread their seeds, it makes sense they would be here.”

Reatini plans to return to the Galapagos next summer. “I’m excited to come back and explore some of the more remote areas where very little work has been done on these species,” he says. Reatini will compare the data he collected from the central areas versus the more peripheral, outlying areas. He also wants to examine germination and growth rate — variables that aid in an invasion. “I can compare them to guava grown on the mainland to see if more seeds germinate and if they grow faster here, which is typical of invasive species.”