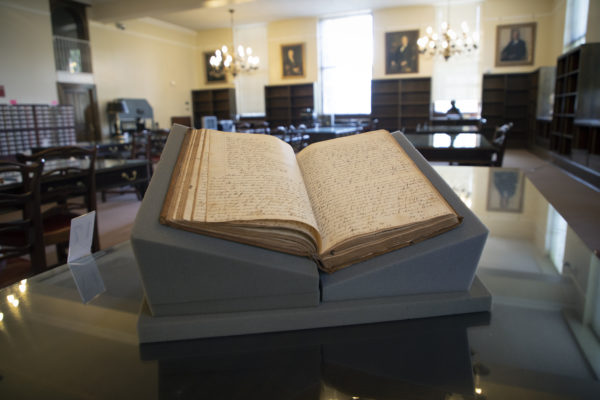

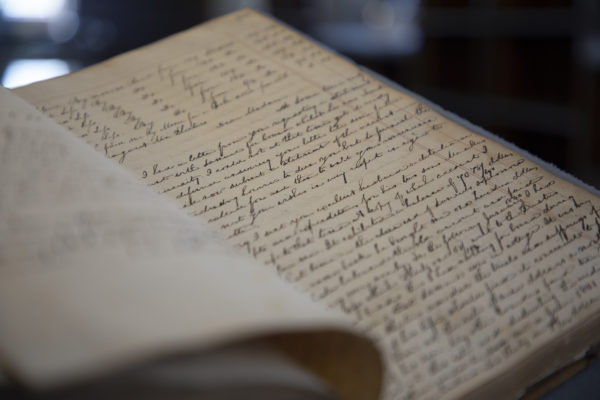

The pages of Elisha Mitchell’s journal are torn in some places, yellowed and littered with spots of mildew in others, and the leather-bound cover is worryingly frayed along the binding. Almost 200 years after it was written, the journal sits under the watchful eye of librarians in Wilson Library’s Special Collections.

The journal — or Folder 14 of the “Elisha Mitchell Papers,” as dubbed by UNC’s Southern Historical Collection — details Mitchell’s life as a professor at the university. The entries supposedly tell of the students Mitchell knew, his fellow professors, and the libraries and laboratories of a growing 19th century campus. Written in its pages are some of the most elemental etchings of what would become a robust environmental science program at Carolina.

But Mitchell, it seems, had no respect for margins, and whatever musings he may have had about the natural sciences are lost in the march of words across entire pages from top to bottom, side to side. The cursive is a series of nearly indecipherable loops and angles. “Raleigh” is scattered throughout, and according to an entry on August 31, 1824, he bought 10 chickens for 83 cents, but otherwise the journal is frustratingly difficult to read.

[row]

[column lg=”6″ md=”12″ sm=”12″ xs=”12″ ]

[/column]

[column lg=”6″ md=”12″ sm=”12″ xs=”12″ ]

[/column]

[/row]

Elisha Mitchell’s journal is filled with an almost-indecipherable script. He wrote about everything from in-depth topics on the natural sciences to lists for purchases. I photos by Alyssa LaFaro

Mitchell and his colleague Denison Olmsted are considered the fathers of environmental research at Carolina. Although Mitchell is more famous for identifying the tallest mountain east of the Rockies — the mountain which would be renamed in his honor after he fell to his death on its slopes — he was also a mathematics professor with a penchant for the natural sciences. In 1825, seven years after he was hired, Mitchell began teaching classes in geology, mineralogy, and chemistry.

“As a teacher,” wrote former university president Kemp P. Battle, “he was most interesting, abounding in illustrations, often humorous, which illuminated the subject.”

Tasked by the North Carolina General Assembly in 1823 to conduct the first geological survey of the state, Olmstead took up the mantle and, on his departure to Yale in 1825, Mitchell continued his work. The survey would be the university’s first foray into environmental research, the first brick of many that would lead to UNC becoming a powerhouse for the natural sciences.

Times of transition

Almost a hundred years passed before UNC’s next major expansion into the natural world. It was the beginning of the Roaring Twenties — America was changing, and rapidly. World War I had just ended, and industrialization and mass production were transforming living conditions, exacerbating problems with air and water pollution, waste management, and water purification. The U.S. Public Health Service had been created less than a decade earlier.

The Division of Public Health’s health officers, sanitary engineers, and sanitary officers during the spring of 1936. I photo courtesy of University Archives

To help address these issues, UNC created the Department of Sanitary Engineering in 1921 — one of the first in the nation.

The new department trained students in sanitary and civil engineering until 1936, when the School of Engineering merged with North Carolina State University’s school to consolidate state resources during the Great Depression.

But the Department of Sanitary Engineering remained at Chapel Hill and gradually embraced the air- and water-quality sciences more generally, becoming the Department of Environmental Science and Engineering in 1962. That same year, Rachel Carson published “Silent Spring,” inspiring the modern environmental movement.

The 1960s and ’70s were times of upheaval: the Vietnam War, the Civil Rights Movement, the Space Race. The worldview that Americans held was changing fast, along with its outlook on the environment. As Congress held hearings about the dangers of air and water pollution and pesticides, and activists were drawing up plans for the first Earth Day, a smaller-scale shift was unfolding at Carolina.

To manage environmental research funding from federal agencies such as the U.S. Public Health Service, Carolina created the Institute for Environmental Health Studies in the late 1960s. After several name changes, it would eventually evolve into the UNC Institute for the Environment (IE), the university’s center for public engagement with environmental sciences.

Having an institute — rather than just an academic department — has been a boon in advancing environmental work at Carolina. Nowadays, IE focuses on air and water quality, environmental financial risk, and is even working with the Department of Defense to train their natural resource managers how to use drones.

“The institute should be a place to organize initiatives that are bigger than anything an individual faculty member can do through their home department, or more interdisciplinary than one department could do alone,” says Richard “Pete” Andrews, professor emeritus of environmental policy who served as director of the Institute for Environmental Studies throughout the 1980s. “It also provides a unified public face for the diverse range of Carolina’s environmental expertise.”

Community connections

In the 1980s, Andrews stood at the helm of the institute. Although it wasn’t as dramatic as passage of the Clean Water Act or nationwide protests, a tipping point for the university would be the day that doctoral student Frances Lynn walked into Andrews’ office in 1985.

Lynn was an activist involved with the occupational hazards of cotton dust among mill workers, and she wanted to move from an organizing role to research-based support for underserved communities.

“She was really a brilliant person,” Andrews says. “She conceived the idea of the Environmental Resource Program. We were seeing a lot of issues pop up around the state and in communities that didn’t have universities in them to provide the science they needed.”

The Environmental Resource Program, an initiative to connect UNC environmental faculty with research needs expressed by North Carolina communities, took off under Lynn’s guidance. The program educated K-12 teachers on how to teach environmental science — for example, bringing recycling into their classrooms — and brought researchers into communities to study issues such as air and water contamination.

“Back then, environmental funding agencies and researchers in environmental sciences weren’t really thinking about that kind of community-responsive work,” says Kathleen Gray, who is now the director of the program, which was renamed the Center for Public Engagement with Science in April 2019. Lynn hired her in 1999.

[row]

[column lg=”6″ md=”12″ sm=”12″ xs=”12″ ]

The original staff of the Environmental Resource Project (from left to right): Fran Lynn, Melva Okun, Mary Beth Powell, and Pete Andrews. I photo courtesy of Pete Andrews

[/column]

[column lg=”6″ md=”12″ sm=”12″ xs=”12″ ]

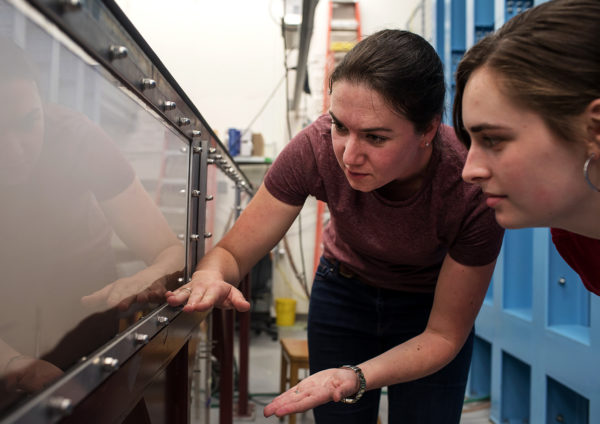

PhD student Kaylyn Gootman (left) works with Savannah Swinea, a 2019 B.S. student supported by CPES during her time at Carolina, on a streambed clogging experiment. I photo by Johnny Andrews

[/column]

[/row]

“Fran and Pete were some of the early adopters who said, ‘Our university, this public institution serving our state, needs to be responsive to citizen concerns and questions on environmental science,’” Gray says.

Within 10 years of its conception, the Environmental Resource Program was a trusted resource for environmental groups and communities around the state. It took the paper-based Toxics Release Inventory, a resource that laid out how much hazardous waste different industries were permitted to release, and published it as a database using an emerging technology called the internet.

“All this was happening at a time when we didn’t have cell phones or even great computer access,” Gray grins. “It’s interesting to think about how things have changed.”

The internet broke down geographical barriers and meant that researchers could easily connect with people in other parts of the state, country, and world about environmental problems and solutions. It became easier to have voices heard, but also to hear them.

Today, the center emphasizes citizen science, air- and water-quality education, internships for undergraduates, environmental science programs for youth, and professional development for K-12 teachers.

“Given the resources that the program started with, it did incredible things,” Gray says. “We’ve been really fortunate to be able to increase those available resources and also partner with dynamic faculty to bring resources together so we can do a lot more.”

Emphasis on education

By 1980, the University had accumulated a wide range of environmental teaching and research expertise, but that knowledge remained fragmented across many of its departments and professional schools. In 1982, the botany and zoology departments were consolidated into a single biology department, which greatly increased its expertise in molecular and medical biology, but diminished its emphasis on the study of plants, animals, and ecosystems, as well as the field research associated with those subjects.

For undergraduates at this time, there was no specific major offered in environmental sciences or environmental studies. Although there were opportunities for students to study ecology away from the university — such as at the university’s Institute for Marine Sciences in Morehead City — there weren’t many opportunities for students on campus.

UNC marine scientist TK teaches a group of students about sediment sampling at the Institute of Marine Sciences, circa 1980. I photo courtesy University Archives

In the early ’90s, nearly 200 faculty members had identifiable teaching or research expertise in the environment. But most of them lacked organizational support to orchestrate large-scale interdisciplinary research projects that were increasingly needed to understand complex environmental and ecological processes and the human activities that affected them.

Founded in 1991, the Carolina Environmental Program created new opportunities for students to get out into the field. Over time, the program founded six field sites in places such as Thailand, the Appalachian Mountains, and the Galapagos Islands. The sites are still extremely popular today.

“The Carolina Environmental Program really revitalized field education,” Andrews says. “The students love it — going to these field sites around the country and around the world really enriches their education.”

Another result of the program’s creation was undergraduate majors in environmental studies and science, something that students had requested for nearly two decades. After some worries about funding and competition with other majors — particularly with chemistry and biology — the majors were introduced under the joint direction of the College of Arts & Sciences and the Carolina Environmental Program.

In 2006, the program was dissolved and the majors fell under the total direction of the College of Arts & Sciences through the Curriculum for the Environment and Ecology. The curriculum was restructured in July 2018 as the Environment, Ecology, and Energy Program (E3P), in order to broaden its focus for issues like clean technology and smart cities.

Campus conservation

Although research, coursework, and outreach outside of campus had been flourishing for years, there wasn’t much practical environmental progress on the campus at large until recent decades. The administration had made strides with energy conservation — especially after the energy crisis of the 1970s — and had several other notable environmental accomplishments to its credit such as funding the town’s free bus system to reduce traffic congestion and committing to no net increase in water runoff during its building boom of the 1990s. But the university had not yet made a systematic commitment to environmental sustainability across all its operations.

Brad Ives, the associate vice chancellor for Campus Enterprises, noticed this when he was pursuing his undergraduate degree in political science and a law degree at UNC in the late 1980s.

“Recycling was really just starting. Back then, it would have only been aluminum cans,” he says. “There was no plastic recycling. But gosh, I don’t even think there was a collection. You’d have to take your cans somewhere. There were no recycling bins on campus that I recall.”

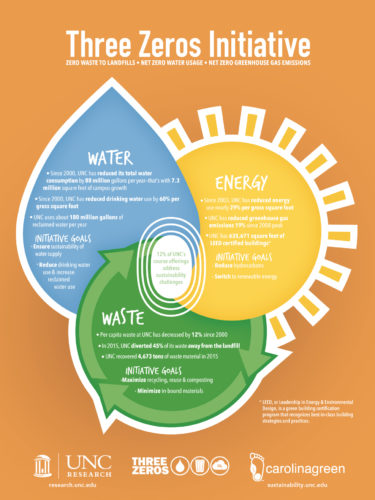

Ives, who joined the team at Campus Enterprises in 2015, also serves as the university’s chief sustainability officer. He has worked hard in the last few years to expand waste-reducing initiatives across campus through the Three Zeros Environmental Initiative, which was launched in Fall 2016.

Ives, who joined the team at Campus Enterprises in 2015, also serves as the university’s chief sustainability officer. He has worked hard in the last few years to expand waste-reducing initiatives across campus through the Three Zeros Environmental Initiative, which was launched in Fall 2016.

“Carolina has always been known as a leader on environmental matters, and it just seems natural that we should be able to deliver on that,” Ives says.

The goal of the Three Zeros initiative is to reach net zero water, zero waste to landfill, and net zero greenhouse gases. It has seen success so far: There has been a 22 percent reduction in greenhouse gas emissions since 2007, and a 63 percent decrease in water use since 2000.

To reduce waste, one target was the dining halls. For the last three years, students have composted cups, cutlery, and food containers instead of throwing them away. Decreasing waste also cuts down on greenhouse gases, since a byproduct of organic matter breaking down in landfills is methane.

“I grew up when we had the Clean Water Act, the Clean Air Act, and a lot of focus on water quality. That was a big part of the ‘Woodsy Owl’ generation,” Ives says. “When I’m hearing about traditional environmentalism with global warming and climate change, all that is coming together.”

Ives says there’s a lot more work to do, especially with the cogeneration power plant that supplies much of UNC’s electricity. Ives also believes that enacting change on the state level — such as the passage of a law that allows the university to affordably offset electricity usage with solar energy — is a path toward lessening the university’s carbon footprint.

Focus on the future

Although environmental programming at UNC has come a long way, there is still a lot to do and understand. Priorities are changing, and issues that were less alarming in Mitchell’s days — such as global climate change, overpopulation, and waste management — have made their way to international attention.

Environmental science and studies majors from E3P’s class of 2019 celebrate their graduation. Some of the students will go to work for the National Park Service, laboratories, and mass transit companies. I photo courtesy of Annie McDarris

The Institute for the Environment, the Gillings School of Global Public Health’s Department of Environmental Sciences and Engineering, E3P, and the university’s facilities and operations units plan to be at the forefront of it.

“Despite a course that has included some challenges, we’re in a really good place now,” says Michael Piehler, the current director of the Institute for the Environment. “Environment is a global priority and Carolina is poised to meet key challenges we are facing. I’m really optimistic that there’s both the will and the way to do wonderful things.”