Listen to the story:

On Rose Mary Xavier’s daily walk to school when she was 6 years old, she would pass an older man who was almost always sitting in the same place on the street. Despite the hot temperatures of her hometown of Tangasseri, India, the man always wore a lot of clothing. But Xavier was most surprised by how he talked and laughed to himself when no one else was around.

One day, Xavier noticed the man was bleeding from his hands and legs, still chuckling to himself like nothing was wrong. She finally asked her uncle about it. He explained that the man had probably been bitten by a stray dog and was sick. When Xavier asked why the man wasn’t in the hospital, her uncle dismissed her.

“Girls aren’t supposed to ask questions,” he responded.

But why would somebody who was sick not be in the hospital? That question has stayed with Xavier throughout her education and career.

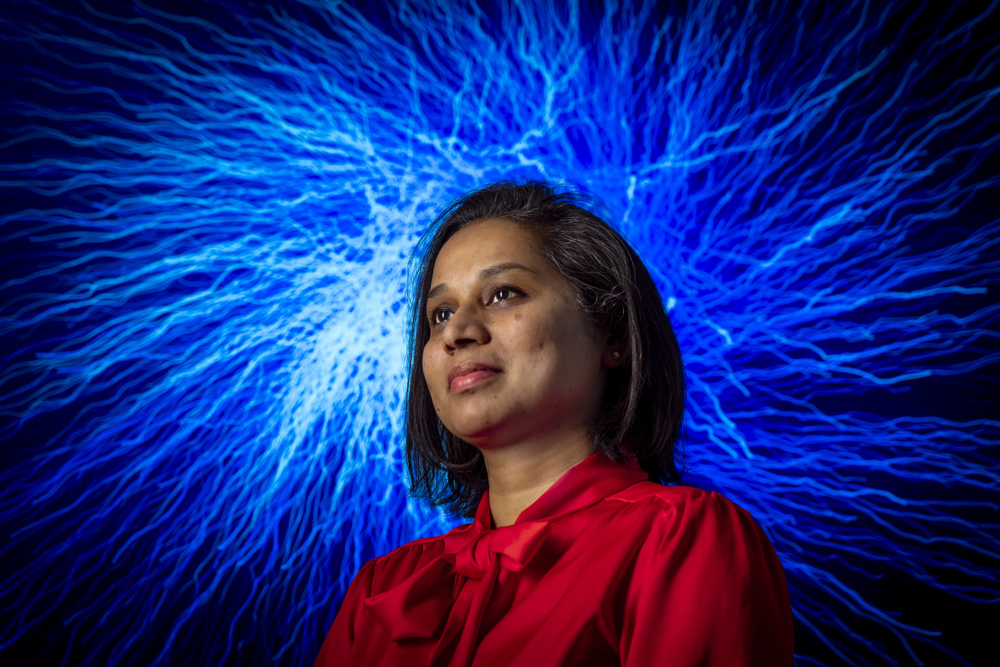

Xavier is a first-generation high school and college graduate. She is a psychiatric nurse practitioner with a PhD in nursing and a doctoral certificate in cognitive neuroscience. Now, as an assistant professor within the UNC School of Nursing, she studies the brain and how it changes in patients with severe mental illnesses, particularly schizophrenia.

While earning her undergraduate degree in nursing, Xavier learned that when people have a psychotic break, they often don’t understand what’s happening and experience hallucinations and delusions, making it difficult to convince them to seek treatment.

“We have this brain,” she says. “It helps us understand the world. It’s supposed to give us awareness. But something happens to that awareness in people with schizophrenia and psychosis.”

This phenomenon, which prevents people from knowing they’re sick and that the symptoms they’re experiencing are part of this illness, is called impaired insight. But having a name for this experience isn’t enough of an answer for Xavier.

“This organ that grounds us and helps us make sense of ourselves and the world — what goes wrong?” she reflects. “What changes happen?”

A multi-pronged approach

In 2019, these questions led Xavier — who goes by “Dr. X” — to Carolina, where she founded the X Lab. She and her team study schizophrenia and how the nervous system creates symptoms. They also research the role biology and genetics play in disease development, new methods to improve clinical care and treatment, and how to make the health care system more equitable for patients with schizophrenia.

Schizophrenia is a complex illness. Strong genetic, social, and environmental factors make it difficult to predict the risk of development, and current treatments are unable to address all symptoms.

For example, doctors frequently offer patients medication for treatment, which targets some biological causes of schizophrenia to reduce symptoms. But available medications don’t target all symptoms, and some patients don’t respond to them.

That’s why Xavier and her lab are assessing resistance and responsiveness to clozapine, the only FDA-approved medication for treatment-resistant patients.

“Though not a cure, medications treat distressing symptoms in patients and can help improve their functioning and quality of life,” Xavier says. “My hope is that this study will help us identify mechanisms of how clozapine works, as well as identify early on who it would work for and who it wouldn’t.”

Xavier supplements medication studies with other approaches to address schizophrenia, which are aided by her background in nursing, psychiatric mental health, genetics, cognitive neuroscience, and neuropsychiatry.

In one study with the Pennsylvania State Hospital Collaborative Group, Xavier and her colleagues investigated why patients with schizophrenia and treatment-resistant psychosis have an increased prevalence of rare copy number variations. These alterations of the genome increase the risk for different neuropsychiatric disorders, including schizophrenia.

Rare copy number variations impact neurodevelopment and affect multiple organ systems, creating a slew of symptoms that often lead to genetic screening and related services — and an earlier disease diagnosis.

But the patients in Xavier’s study didn’t show enough classic symptoms to be identified for the screening. While cognitive impairments are relatively common in patients with schizophrenia, they are often only recognized if the impairment is significant enough to be diagnosed as an intellectual disability.

Fewer screening opportunities and less access to health care services overall means that most people with severe schizophrenia remain undiagnosed and untreated into adulthood.

“My hope is that our study will facilitate screening for these copy number variations early on in schizophrenia — ideally during the diagnostic workup — so that they can get the right care,” Xavier says.

Making research accessible

Historically, many people with severe mental illnesses have been excluded from research because of accessibility issues. These include lack of transportation, particularly given that many severely ill patients live in residential care areas far from academic research centers; lack of resources to identify available research opportunities, such as access to the internet; and the design of many research studies to intentionally exclude severely ill patients.

“When this happens, we are systematically excluding people,” Xavier points out. “It’s almost a privilege to be able to participate in research.”

This is where Xavier’s position as the director of the Biobehavioral Lab (BBL) comes in. The BBL is a core facility at UNC-Chapel Hill. Equipped with molecular biology and behavioral lab spaces, it provides resources and technology to aid research happening both within and outside the Carolina community. As the director, Xavier assists researchers using the facilities and advances the BBL’s scientific mission, which includes making research more accessible.

For instance, she is working on a project assessing the accuracy of dried blood spot samples, a method of collecting blood by pricking the finger and squeezing a drop onto a filter paper card. Much simpler than drawing blood from a vein, this is how newborn children are often tested for certain genetic disorders.

If this method can be modified to measure inflammatory biomarkers, study participants could collect and send in their own samples for research studies, eliminating the transportation barriers for participation.

“To get venous blood, we need someone highly trained to do that, but dried blood spots are just a finger stick away,” Xavier says. “To make research accessible we need to have the right methods and if we get the methods right, more people will have access to research.”

Tangential to accessibility is the need for more diverse participants in psychiatric research, which Xavier also studies. One of her most recent papers demonstrates and unpacks a gap in race in mental health studies.

“Psychiatric genetics research is predominantly Eurocentric, and individuals of non-European ancestry continue to be significantly underrepresented in research studies, [which has the] potential to worsen existing mental health disparities,” she writes in the paper.

In addition to helping research participants, Xavier strives to make research more accessible for students — something she herself had to fight for in both her undergraduate and graduate programs.

“One of the things I try to do is actually make space for people to get those experiences, regardless of where you’re coming from or what your background is, even if you don’t have any idea what you want to do,” Xavier says.

Since 2019, she has mentored over 30 students, from developing research experiences for high schoolers to training undergrads and PhD students on data collection methods and use of the lab’s facilities.

Even though multiple decades and degrees now separate Xavier from her childhood in India, she still thinks about that man on the side of the road.

“I think I now recognize some of the things that puzzled me when I was little,” she reflects. “I recognize the fear of the distressing symptoms, the isolation from experiencing something that no one truly understands, and the pain of a stigmatizing illness. And I want to at least try to make that better.”