Engaging in research equips undergraduates with essential skills, from problem solving to project planning to collaboration to data collection and analysis — abilities that will serve them well as they transition into the professional arena.

This May, over 7,000 Carolina undergraduates will go on to be the next generation of scientists, teachers, doctors, artists, public policy analysts, and much more. Their involvement in research during their time at UNC-Chapel Hill has prepared them to address some of the world’s most significant challenges.

“In research, you’re taking the skills and the theory you’re learning in the classroom and applying it in a practical scenario,” explains Karthik Ramakrishnan, a senior who has worked in several research labs during his time at Carolina. “It teaches you that not everything in theory works out in practice. You will fail a lot more than you succeed. Learning how to handle failure and recover from it emotionally and analytically will help you in so many facets of life.”

Impact Report

![]()

Undergraduate research at UNC-Chapel Hill prepares students to be future leaders by fostering innovation, collaboration, and the critical thinking skills needed for solving the world’s biggest challenges.

![]()

16,000 + undergraduate students are engaged in research at Carolina, from the humanities to health care.

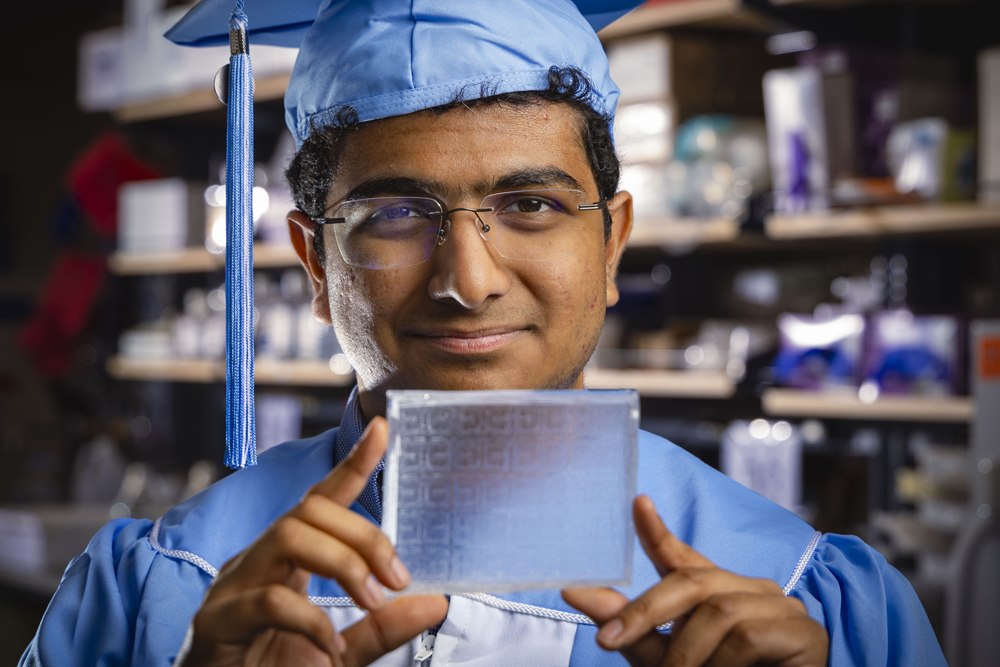

Karthik Ramakrishnan | biomedical engineering

When Karthik Ramakrishnan was in high school, he came down with a terrible cold and, upon blowing his nose, was shocked — and a little grossed out — by what had come out.

“It was probably the worst I’d ever seen,” Ramakrishnan recalls. “So naturally, I googled: Why is my mucus so thick?”

He went down a rabbit hole.

He read about concepts like viscosity — fluid thickness — and flow. By the end of the day, he’d basically taken an introductory fluid mechanics class and realized he enjoyed learning about biology from a physics-based perspective, a field known as biophysics.

“I knew then that this is what I wanted to do for the rest of my life,” Ramakrishnan shares.

Now, the biomedical engineering major is working in Sarah Shelton’s lab to study how blood viscosity affects cancer progression. Through a process called metastasis, cancer cells can spread from the primary infection site to other parts of the body via the bloodstream or the lymphatic system. Once they settle in the new location, they can begin to grow secondary tumors, making cancer more challenging to treat.

While there have been several studies on the biochemical characteristics of metastasis, Ramakrishnan is looking at the physical factors that change as the cancer spreads and is exploring ways to target these processes to slow or stop that progression.

Research like this requires resilience, according to Ramakrishnan, who’s worked on a handful of projects that have required consulting with Shelton and other lab members while systematically tweaking his protocols.

“You have to be the one that’s motivated to come in every day and do the work,” he shares. “There’s going to be days when you’re banging your head on the wall because nothing is working. That’s just science. It’s a slow process, but that’s how you learn and get better, and it makes the successes that much more worth it.”

In Fall 2025, Ramakrishnan will start a PhD program in mechanical engineering at the University of Rochester. He plans to study the physics behind how the human brain clears waste, like toxic proteins, during sleep and how neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s arise when the brain struggles to get rid of that waste.

Kiara Rodriguez | human development and family science

As Kiara Rodriguez watched her little brother grow up, she couldn’t help but notice how different his childhood was from hers. She saw him and his friends engage with social media at a much younger age, exposed to adult consumer culture far earlier than she ever had.

This realization hit even harder when she compared a recent Christmas wish list to that of her younger teen cousin. Both wanted the same trendy items, like a Stanley cup and clothing from Lululemon. Rodriguez wondered if viral trends were shaping youth identity earlier, or if each generation simply perceived the next as growing up too soon.

To learn more, she began working with education researcher Dorothy Espelage on a senior thesis project. Together, they discovered the term age compression — a marketing and social phenomenon where children feel pressured to adopt interests, behaviors, and consumer habits typically associated with older age groups.

In today’s world of viral fashion trends and TikTok-fueled consumer culture, younger children are more likely to be interested in high-end beauty brands, designer fashion, and social media trends that were once geared toward teenagers or adults. This is evident in the rise of the “Sephora kids” trend in which tweens purchase and use makeup and skincare products, often with ingredients designed for adults.

Rodriguez believes these trends are shifting youth identity and can lead to developmental consequences if not discussed. That’s why she’s studying how age compression influenced previous generations and how it impacts tweens today via social media. She hopes that her research will reveal a better approach for parents to communicate with their kids about fashion, social media, and self-expression.

“It’s hard enough for me as an adult to figure out my own identity and why things matter to me,” she explains. “And I know it’s even harder for tweens who have a bit more freedom but aren’t able to do exactly what they want. I think having outlets, even if they are seen as more adult, can be so beneficial if tweens have the right support and media literacy education.”

Rodriguez believes her time at the UNC School of Education has helped build a foundation for a future in health care. While she wants to continue her research, she plans to study radiation therapy after graduation.

“My mom always jokes that if I could be a professional student, I would be,” she shares. “I love to learn, and I think people are really interesting.”

Nico Gleason | public policy and global studies

As a child, Nico Gleason begged his mother to take him to the railroad tracks at the center of town so that he could watch the freight trains rumble through his hometown of Greensboro, North Carolina. He was captivated as he watched the long line of cars decorated with vibrant colors and logos, stretching for what seemed like miles, speeding down the track.

“There was just something about trains,” Gleason recalls. “I love that they’re these big lumbering pieces of machinery, and I’m in awe of their mechanical ability.”

Now a public policy major, he sees trains in a new light. Not only do they play a critical role in U.S. commerce — moving nearly 1.5 billion tons of freight each year, according to the Association of America Railroads — but they also offer renewable solutions for transporting passengers.

Gleason’s research journey began through coursework with public policy professor William Goldsmith, who encouraged him to integrate his personal interests into academic work.

Delving deeper into the subject, Gleason found systemic issues related to the interaction of freight and passenger rail services. This led him to research and write a paper on how often passenger trains are delayed and for how long throughout the year. By tracking these delays, he aims to understand the reasons behind them.

His paper also examines the physical infrastructure of train networks, linking the design of the tracks and stations to train performance. The goal is to come up with practical solutions that can help trains run on time more consistently.

“There are some very complex problems in this world, and we often don’t have well-thought-out solutions for them,” he says. “What excites me is developing creative solutions.”

Gleason encourages incoming students who want to get involved in research to pursue topics that truly interest them.

“It doesn’t have to be your childhood obsession with trains,” he says with a laugh. “Just immerse yourself in research because that will produce your best work and will also be the most personally fulfilling.”

After graduation, Gleason plans to take a few years off from school while continuing his research independently. He hopes to eventually attend graduate school.