Jeff Brown accidentally bumped into a white girl while trying to catch a train. Lacy Mitchell testified against a white man charged with rape. Berry Noyse was accused of killing the local sheriff and was never given due process. All these events produced the same outcome: The person was lynched.

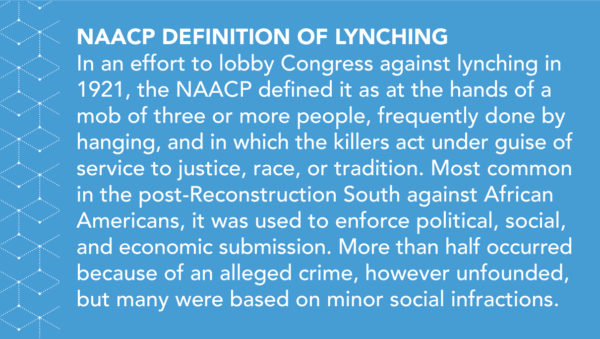

In 2015, the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) released “Lynching in America, Confronting the Legacy of Racial Terror.” The report is second in a series examining the trajectory of American history and explains how lynching became a phenomenon in the United States, especially between 1880 and 1940.

While teaching a class about the rural South, American studies professor Seth Kotch shared the report with his students.

“We were reading about rural economies, how people communicated with one another, and how customs were translated generationally – and lynching is one such custom,” he says. “It’s specific to the South in the same way that some of the other traditions we were talking about were specific to the South.”

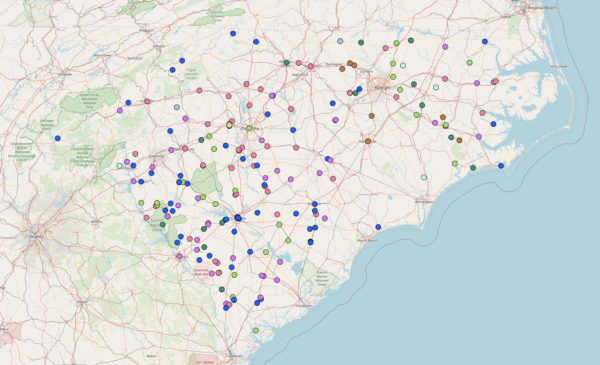

In response, the class made “A Red Record” – an interactive map of North Carolina where visitors could click on data points to learn about individual lynchings.

“Just seeing these incidents laid out in this familiar map, I thought, was powerful,” Kotch says, explaining the idea was to disrupt this familiarity. “For a lot of students, things happened in that comfortable space that they’re not seeing.”

Seth Kotch’s classes have mapped lynchings in North and South Carolina, Tennessee, Arkansas, and this fall will continue with Virginia.

Seth Kotch’s classes have mapped lynchings in North and South Carolina, Tennessee, Arkansas, and this fall will continue with Virginia.

The group used the EJI report and Vann Newkirk’s “Lynching in North Carolina: A History 1865-1941” as starting points. For each reported lynching, they dove into online archival databases to gather information like the date and location of the murder, victims’ names, and the narrative around the tragedy.

In total, the class found 181 cases of lynching in North Carolina between 1866 and 1947. Kotch suspects that is a conservative number, assuming many were either unreported or records have since been lost.

“It was kind of shocking how widespread the phenomenon was,” he says. “If you look at the map itself and get rid of the cartesian lines it still looks like a map of North Carolina.”

Subsequent classes have mapped South Carolina and Tennessee, Arkansas, and this fall will cover Virginia. In addition, Elijah Gaddis, a former UNC graduate student and current assistant professor at Auburn University, will map Alabama. Kotch’s goal is to map the entire former Confederacy.

A changed landscape

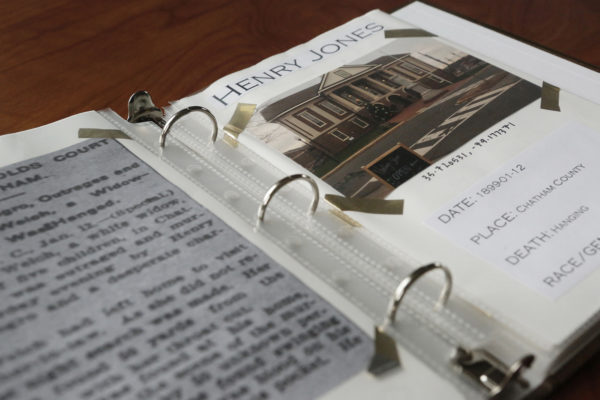

Mackenzie Drake, a student in Kotch’s Spring 2016 semester class, took the project a step further by photographing 16 lynching sites.

Her route wound through backroads and major highways, rural communities and cities, in neighborhoods and town centers. She was often struck at the juxtaposition between the site’s history and its current state – next to a high school, in a backyard, and under a bridge with hundreds of commuters zooming across.

Mackenzie Drake, a former student of Kotch, paired photographs of lynching sites with copies of archival newspaper clippings about each murder.

“I feel like actually going there and documenting that with a picture, for me, it kind of honored the people it happened to,” she says. “This is something that we shouldn’t forget about.”

Drake worked within a 70-mile radius from Chapel Hill. Using Kotch’s map, she picked sites based on the abundance of available information, including latitude and longitude pairings.

None of the sites she visited memorialized the lynching. “It was crazy to think that probably every day, hundreds of people pass by this place and it’s not recognized at all,” she says.

The project has given Drake pause when thinking about the history behind places she visits on a day-to-day basis. This is the response Kotch hopes for.

“Part of what Jim Crow did was make comfortable environments uncomfortable for people of color,” he says. “Restaurants, beaches, parks – all these spaces were made hostile. Hopefully, what this digital project can do is allow people who otherwise wouldn’t encounter their daily environments as uncomfortable or challenging see them in a different way.”

Tackling difficult topics

Drake previously learned about lynchings in high school but says her education on the topic was glossed over and misconstrued.

For example, before Kotch’s class, Drake thought these murders were primarily carried out by white supremacists like the Ku Klux Klan. In reality, they were normalized throughout the white southern community and became a public spectacle.

Kotch hopes to combat this lack of understanding in future generations. “We know that students aren’t learning about what’s called ‘hard history’ often in their high school classrooms,” he says. “Hard history is history of things like enslavement, lynching – difficult stuff.”

[row]

[column lg=”6″ md=”12″ sm=”12″ xs=”12″ ]

[/column]

[column lg=”6″ md=”12″ sm=”12″ xs=”12″ ]

[/column]

[/row]

Seth Kotch talks to teachers about lynching during the Southern Oral History Program and Carolina K-12 teaching fellows workshop at UNC.

In collaboration with Carolina K-12, high school teachers from around the state will be invited to UNC to learn how to disseminate this information to their students. Kotch is also developing free teaching materials that align with state standards and can be used as tools in the classroom. He hopes to start with North Carolina schools and eventually expand to other states.

Teachers often find lynching discussions difficult because it can make students uncomfortable, Kotch says, but discomfort is invaluable for growth.

“We need to learn about these histories because there’s no way to confront their legacies – which are real and manifest – without learning about their origins,” he explains. “Ignorance doesn’t inoculate you against the effects of what you’re trying to ignore.”

Telling the whole story

Like Kotch, American studies and anthropology professor Glenn Hinson was inspired by EJI’s report – so much so that he contacted the organization to see how he could help. Although numerous studies investigate the details of lynchings, there are far fewer that focus on family members of victims. Hinson wants to hear those stories.

When people talk about lynchings the narrative ends at the moment of the murder, Hinson says, but that is where his work begins.

“Our goal is not to retell a gruesome history, but to speak to histories of resilience,” he says. “There were generations of folks since then that carried that knowledge, that memory, and carried it forward through history. What happened to those families? What were those stories? And most importantly, what are the stories of those descendants now?”

With the Descendants Project, Glenn Hinson and UNC undergraduate students are tracing the family lineage of lynching victims and gathering oral histories of descendants.

Before introducing “The Descendants Project” to a class, Hinson wanted to see if it was viable and searched for family members of Eugene Daniel – a 16-year-old boy killed in New Hope Township in 1921.

Through online archives, Hinson traced Daniel’s family from 1910 until 1940. After that, the trail grew cold and he became increasingly doubtful the project would prevail.

That was, until he came across a 2014 obituary of Daniel’s niece. Hinson saw that a son of the deceased woman was from Oxford. He opened the phone book and found a name that matched.

After a few rings, Johnny Webb picked up. Hinson confirmed that Webb was the correct person mentioned in the obituary, explained the project, and told Webb he was a descendant of a lynching victim.

“As I can remember, it was a pretty casual conversation and just slowly got around to that,” Webb says.

Hinson understands calling a stranger to inform them about a tragedy in their family can be controversial, especially if the person was unaware of the murder. He recalls many times people hung up on him, but also others who have expressed gratitude in learning about this history.

Webb was one of those who stayed on the phone. “I think it’s something that needs to be known,” Webb says. “It doesn’t need to be swept up under the rug – people need to know how people really acted in those days.”

Webb didn’t know about the murder but had always suspected something may have happened. “Somebody down that [family] line suffered or had to go through worse trials and tribulations than I’m going through for me to be able to have some of the rights that I have as an African American,” he says.

With Webb’s willingness to participate, frustration Hinson experienced up to that point washed away. “That’s what said to me, we can do this project,” Hinson says.

Since 2016, Hinson’s students have collected oral histories from 10 descendants of five lynching victims. The classes have attempted to find many more, but continually run into what Hinson calls “a strategic history of erasure.”

He notes that newspaper articles and even death certificates often didn’t mention family members. Furthermore, census data at that time for African Americans is fraught with inaccuracies.

“You quickly discover that white census takers cared very little for black families,” he says. “You might find so many misspellings that you can’t even locate this person historically.” The same is true for marriage, military, birth, and death records, he adds.

In one case the class found 15 spellings of one woman’s name, some so inaccurate they could only tell it was her by the name of a spouse or child. For the students who were able to find and interview descendants though, Hinson notes how personal it became for both parties.

“For a lot of the members of the class this was a profoundly transformative experience, as it has been for me, to grapple with the erasure and see how difficult it is to find these stories,” he says.

Reconciling the past

This fall marks the start of an undergraduate research course dedicated to Hinson’s project. Students will continue to search for families and will also work with community leaders to bring an EJI public memorial to Warren County.

A descendant involved in the project suggested the idea. “Warren County, the history is deep,” Hinson says. “The descendant from the county said: We don’t want students just to talk to families, there are bigger stories here and you have to put it in context.”

That context includes racially-charged moments in the county’s history.

Jereann King Johnson sits in the sanctuary of Oak Chapel AME Church in Warrenton. The church was one of the only local institutions that fought for the release of Matthew Bullock’s brother and cousin prior to their death.

Warren County was the site of an infamous 1921 double-lynching in which Matthew Bullock, the intended victim, fled to Canada and a failed extradition ensued. With Bullock gone, the mob instead lynched his brother and cousin.

Another notorious account surrounds Soul City – first proposed in 1969, it was a town that emphasized providing opportunities for minorities and the poor. The project fell through, and part of the site became a federal prison.

It was also the start of the environmental justice movement in 1973 with a lawsuit brought against Ward Transformers Company for dumping thousands of gallons of chemicals on the roadsides of mostly low-income, African-American communities. The case brought national attention to the issue of institutionalized environmental racism.

Jereann King Johnson, a community activist working to preserve African American legacies in Warren County, says this history affects residents to this day.

“That has been sort of the veil that people see the community through,” she says, “Particularly black people who have lived here all their lives.”

A long-time friend of Hinson, Johnson is interested in helping UNC students learn about these stories. Although she didn’t move to the area until the late ‘70s, she sees similarities in the history of her own hometown.

“I grew up in the Jim Crow South, in southwest Georgia, and heard stories of lynching and abuse of black folks by white people and it’s something you don’t forget,” she says. “As much as you move toward a desegregated state, you’re still reminded of injustices there.”

Although race relations have obviously improved in Warren County over the years, Johnson sees a general avoidance in discussing race issues as stunting future growth. She hopes Hinson’s work will help guide that conversation.

Some people may interpret discussing racial violence as provoking a troubled history, but that’s not Hinson’s aim. “It’s not about stirring up the past, it’s forcing an accounting,” he says. “Reconciliation can never occur until there is an accounting.”