Femurs, tibias, teeth, ribs, and jaw bones cover a large table from end to end — just a typical day at work for UNC researcher Benjamin Arbuckle. As a zooarchaeologist, Arbuckle studies the human-animal relationships of ancient peoples and how those relationships are the foundations of modern society.

“We generally assume this sort of Western idea that man makes himself, we create all the stuff around us with our own hands,” Arbuckle says. “We’ve very quickly lost sight of the fact that only about 120 years ago animals were the labor power. That was the engine that fueled a really big world.”

Arbuckle and fellow zooarchaeologist, Heather Lapham, emphasize this long history extends to every aspect of civilization. Religion and worldviews, social structures, mass production of agriculture, the rise of societies through trade and military conquest — even our physiology is influenced by our ancestors’ relationship with animals.

Influences everywhere

When one thinks about the use of animals in society, they might immediately think of meat for sustenance, hides for warmth, or strength bridled for labor. But the ways animals have influenced human history goes far beyond that.

Take milk, for example. It’s pretty strange that some humans drink the milk of other non-human animals. In theory, all adults should be lactose-intolerant. It’s only because of the domestication of goats and cows 10,000 years ago —and a few hundred generations of people having really bad stomachaches — that some adults can now digest lactose.

A core symbol in Judeo-Christian belief is that of the shepherd, treating the world and others with the care that a herder has for his flock. This worldview stems from humans’ relationship with sheep, one of the first domesticated species in the Middle East.

When European colonizers arrived in North America, they brought with them diseases like smallpox, influenza, and the measles, decimating Native American populations. These viruses, born out of domesticated livestock, also caused outbreaks in Eurasia. The vital difference was that over thousands of years Europeans became more immune to these infectious diseases by living in close contact with livestock. Native Americans did not have this domestication of livestock nor these immunities.

When the scientific field of archaeology exploded in the 19th century, excavators weren’t interested in animal remains. They were basically seen as trash — and treated as such. Animal bones gave insight into what ancient peoples were eating, but there wasn’t much use beyond that.

Even in the 1990s, Lapham was questioned about the importance of zooarchaeology. While writing her dissertation on a Native American site in Virginia, excavated 20 years prior, an excavator told her animal bones weren’t saved because they already knew those people were eating deer.

“He actually wrote me an extensive letter saying, ‘We know they ate deer, why are you doing this research?’” Lapham laughs. “But there’s a lot you can get out of it. I became interested in zooarchaeology because of the broad range of questions it can answer about the past that go far beyond diet and sustenance.”

These questions have led Arbuckle and Lapham on research trips across the United States, Mexico, and Turkey as they slowly piece together an accounting of how animals have changed the course of civilization.

Brother bear

Lapham is particularly interested in how animals were used to strengthen societal relationships by trading animal products, like skins or meat, and practicing ritual sacrifice. Her work focuses on indigenous societies from North Carolina and Virginia from the years 1500 to 1700, as well as in southern Mexico from around 500 A.D., about 1,500 years ago.

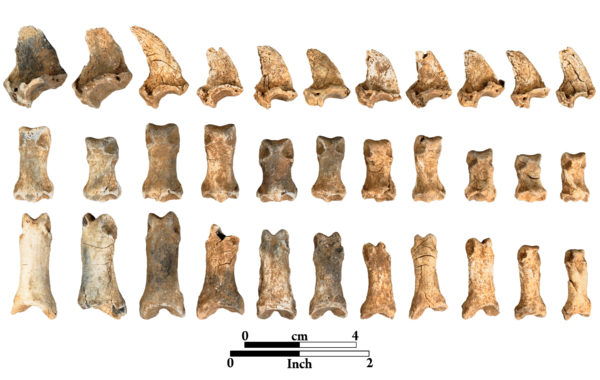

Throughout Native American culture, deer and bear were important. By studying these artifacts, which are mostly bone remains, Lapham can track indigenous peoples’ relationship with early Spanish and European settlers in North America.

A variety of bones from bear paws were excavated from the Fredricks site near Hillsborough. Native Americans in this area considered bear paws to be a delicacy. Photo courtesy of Heather Lapham.

“You can see how participation in the 17th-century deerskin trade changed a whole system of who was gaining power in Native communities, who was gaining access to these prestige goods in exchange for deer hides,” Lapham says.

The Berry Site in Morganton, North Carolina, is the location of the 16th Century Native American town of Joara and adjacent Spanish fort, Fort San Juan. The Joarans, like many Native Americans, prized bears and bear meat. Many referred to them in kin terms like grandfather, brother, or cousin. The Cherokee, for example, believed that bears could reincarnated in order to always provided food for their people. As such, their remains were treated with high regard and their meat was reserved for important visitors and occasions.

Zooarchaeologist Heather Lapham studies sites in North America to understand the relationship between indigenous peoples and animals.

Early on in their relationship, the Joarans treated the Spaniards like welcome guests — providing a substantial amount of bear meat. By the end of the Spanish 18-month occupation at the fort, though, this relationship changed, and bear meat dropped out of their diet. This indicated that the soldiers no longer held a privileged status in the eyes of the Joarans.

While the sites in the United States convey information about indigenous societies as a whole, Mexico provides Lapham with the opportunity to study human-animal relationships at a more individual level. A town excavation in Oaxaca is much larger than Lapham’s sites in the U.S., and she can focus on particular households and neighborhoods.

“You can look at how people are working together or how they had different specialties related to animals that came together in a single settlement,” she says.

One excavation of a residence in Oaxaca unearthed ritual beads made of dog bones, as well as more than 50 sacrificial offerings of animals, including puppies. Lapham thinks this was the home of lower-level priests or ritual specialists. Another gives the best and most comprehensive evidence of early turkey domestication in the valley.

These findings point to how creative and resourceful these people were, even more resourceful, Lapham says, than most today.

“We’re not dealing with primitive people in the past. They had intricate knowledge about the animals they encountered, the environment they lived in, the plants they used,” Lapham says. “Today, we’re helpless in ways that people in the past weren’t. They were incredibly skilled.”

Horsepower harnessed

When Arbuckle was young, his grandparents’ front yard was littered with giant holes. Aunt Peggy was an archaeologist who used their property as her personal excavation site.

“I would watch from afar, but then when she would leave, I would jump down and look at all the layers. It was very cool,” Arbuckle says. “Archaeologists, sometimes it’s just that you sort of never grow out of digging in the dirt and finding things.”

As a first year at the College of William and Mary, Arbuckle was interested in anthropology and archaeology, but didn’t have a definitive career plan. A class about archaeology and animal bones changed that. “It was a discovery — I loved all of those things and they were letting me do it!” he says. “It just took off from there.”

Benjamin Arbuckle measures an elk antler from the archaeological site Inönü Cave in Turkey, dating to 2000 B.C., during a 2019 excavation trip. Photo courtesy of Benjamin Arbuckle.

Arbuckle studies the role of domesticated animals in the rise of civilizations, particularly in Turkey. One of his main research topics is the domestication of horses, which he says had a bigger impact on humans than any other animal.

Modern-day Turkey has always been geographically important, settled between the Middle East, Europe, and Asia — and also near Africa. This region has been a treasure trove for archaeologists, citing Mesopotamia as the origins of state-level societies and therefore prominent religions and worldviews, agriculture, architecture, and unsurprisingly, the domestication of animals.

“We tend to think the classical world is the origin of Western civilization,” Arbuckle says. “It’s really Mesopotamia, it’s the Middle East that inspired the classical world, but somehow many have just forgotten that step. This is the story of where we come from.”

About 12,000 years ago, these ancient peoples domesticated sheep, eventually followed by goats, cattle, pigs, and donkeys. Horses, though, didn’t come into the picture until several thousand years later.

Some researchers credit societies in Russia or Eurasia, where traditional horse cultures are prominent, for introducing the animals to the region — but no one knows for sure. Through texts and images, records show horses entering the Turkish archaeological record around 2000 B.C., during the Bronze Age. At that time, the region was donkey country and people thought of horses as foreign and barbaric.

It took about another 1,000 years, according to Arbuckle, for them to realize that attaching a chariot to the animal created a military technology like no other.

Workers and students excavate a site dating to 2000 B.C., around the time horses are introduced to the region, in Acemhöyük, Turkey in 2004. Photo courtesy of Benjamin Arbuckle.

“You see that spread in like the blink of an eye archaeologically,” Arbuckle says as he snaps his fingers. “People are just zipping around and communicating like mad. It’s a technology that really catches on.”

In a relatively short amount of time, records indicate horses being used for transportation in Iraq, China, eastern Europe, and eventually the rest of the world.

“Once people figured out how to harness horsepower, man, the world changed real fast. The world got smaller real fast,” he says. “It didn’t change again at that scale until the Industrial Revolution. That’s, to me, the most important human animal story in world history.”

Ancient clues

In the years since Arbuckle and Lapham began working in this field, technology has expanded beyond anyone’s imagination. LiDAR imaging, drone photography, carbon dating, satellite imagery, sequencing ancient DNA, and isotope analysis are all tools researchers deploy.

The biggest technological change in Arbuckle’s work is the development of ancient DNA sequencing. Scientists can now extract tiny amounts of DNA from archaeological samples and sequence that organism’s complete genome.

“There’s so much cool information hiding inside the genomes of animals,” Arbuckle says. “It describes their histories, lineages, and who’s related to whom. Sometimes it’s like Whoops! There’s a new species we didn’t know about before! I’d say it’s the biggest change in archaeology in the 21st century — totally new information about the past.”

In 2006, Arbuckle and his colleagues discovered a species of hybrid donkey they believe was referred to as kunga, an important animal used in battle thousands of years ago. Photo courtesy of Benjamin Arbuckle.

This technology led Arbuckle to one of his favorite animal-related discoveries. In 2006, Arbuckle and his colleagues uncovered a series of donkey burials in Turkey. At first, they thought the remains were from the 1900s. Upon further inspection, they noticed anomalies — the skeletal remains looked like donkeys but their teeth resembled a species of extinct wild ass, called a hemione.

Carbon dating indicated the remains were really from around 1900 BC, and ancient DNA sequencing revealed it was a hybrid between a domestic donkey and a hemione.

“So, why is this cool?” Arbuckle asks. “This is like the first example of human engineering of animals. You can’t domesticate hemiones — they’re too mean. So, this is the first that we’ve ever identified of this hybrid animal.”

These hybrids were used exclusively by elites to pull battle carts. Throughout the archaeological record, images of strange-looking horse-like animals appear over and over again —with big ears and a fat tail. In ancient texts they’re referred to as kunga.

“It took us a really long time to figure out what the heck a kunga was,” Arbuckle says. “Like, 100 years knowing that this word exists to figure out that it’s probably this hybrid animal. To me, it’s kind of nerding out a little bit, but it’s a very cool example of how people did incredible things.”

While Lapham also uses modern techniques in her work, like carbon dating, she says the biggest asset at a researcher’s disposal is a strong comparative collection. The shelves of her lab are lined with bones, collected from road kill, that are used for this referencing.

“It’s like playing a game of memory,” she says. “You consider your 300 to 400 different animal species that you have in this comparative collection and you have to think, Where in that collection am I going to find one that matches?”

Lapham never tires of uncovering artifacts, but says the real pleasure is piecing all these clues together.

“It’s exciting unearthing something, doing the analysis, and then looking at the data and interpreting it,” Lapham says. “That’s where you get the big picture. That’s where you get these interesting stories.”