In 2015, a 7.8 earthquake shook Nepal, and the city of Kathmandu rippled. Buildings swayed, temples toppled — and Lauren Leve was just 90 miles from the epicenter. The disaster destroyed more than 600,000 buildings and killed thousands. The earthquake’s tremble could be felt over 300 miles away in western Bhutan. To survive and witness this event was to survive and witness tragedy.

“Many buildings were damaged irrevocably, and you couldn’t live in them anymore,” Leve shares. “And the temples were destroyed. It was devastating.”

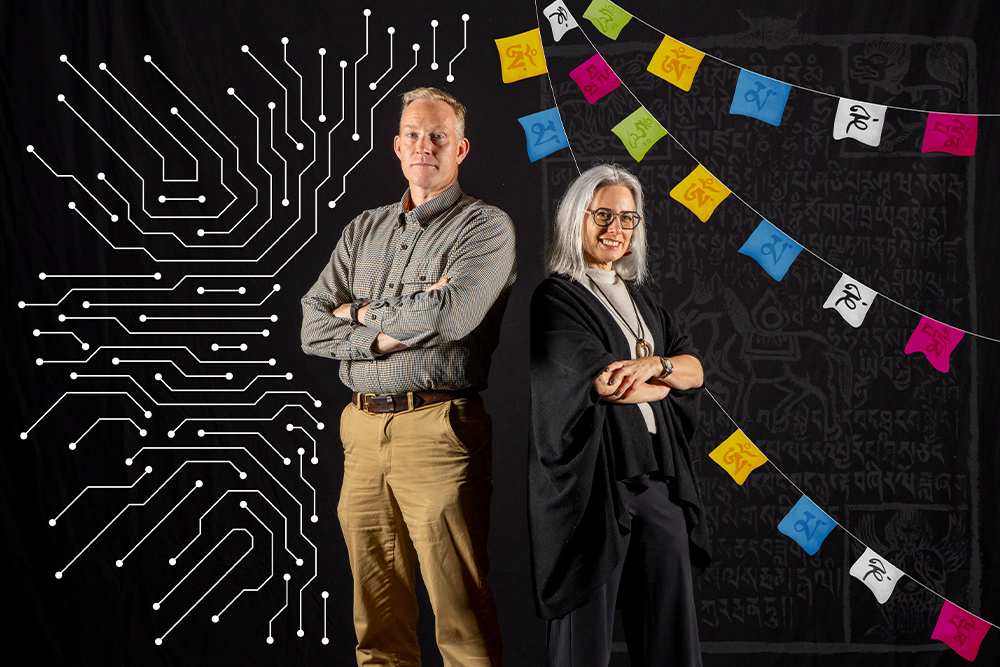

A religious studies professor at UNC-Chapel Hill, Leve has spent 30 years traveling back and forth to Nepal for her research. The 2015 earthquake highlighted the importance of preserving cultural heritage — and motivated Leve to pursue a project to do exactly that.

Now, she is collaborating with Carolina computer scientist Jim Mahaney and Kathmandu locals to document the Swayambjunath, or “Swayambhu,” temple — a monument with deep cultural significance for the region. Today, the team has conducted more than 30 interviews with temple priests, Buddhist monks, devoted visitors, and other people with traditional connections to the site.

They’re also creating highly accurate, photo-realistic models of surviving heritage sites. They’ve captured more than 90 scans and forged a handful of rough models, which they hope to make accessible for VR headsets, the web, and even cell phones for Nepalese people who can’t travel to the temples and interact with the people there.

In addition to creating a tool for Nepalis and other Buddhists around the world, Leve wants to provide opportunities for U.S. college students to work with these data sets and travel to these temples virtually.

“I wanted to find a way to get my students more engaged with the cultural and material aspects of Buddhism,” Leve says. “Because it’s too easy for North Americans to misunderstand Buddhism in places like Nepal based on their experiences of daily life here.”

More importantly, the models act as potential blueprints for when the next earthquake arrives.

“What we didn’t know was how useful this project would be,” Leve says. “Or how much in demand this technology is.”

Reconstruction, one photo at a time

Leve first learned about photogrammetry at a department event, where PhD student Brad Erickson gave a demonstration of his work producing 3D models of archeological sites. She quickly recognized the impact it could have on her classes.

In summer 2018, she returned to Kathmandu with Erickson to try out the technology at some small Buddhist sites where she had relationships with the caretakers. They also conducted a photogrammetry workshop for Nepalese students and professionals. They wanted to provide locals with a resource to rebuild when the next earthquake arrives.

“My goal is to learn from the people I work with on the ground and use this specialized knowledge — which is not currently available elsewhere — to enrich, change, and enhance the broader global cultural understanding of Buddhism,” Leve says.

A room was secured at a nearby college, flyers flooded Facebook, and a handful of applicants were selected to participate in the week of classes. Attendees included local activists and professionals from Rebuild Kasthamandap, a community-led initiative focused on reconstructing the oldest and largest communal building in Kathmandu.

One of them was aeronautical engineer Raj Maharjan, who already had a background in photogrammetry.

“Using better cameras and better software, it was really a turning point for me,” Maharjan says. “That training gave me the confidence to do paid work and also approach the government with better results.”

After the 2018 workshop, Maharjan established a company called Galli Maps, which utilizes advanced photogrammetry skills he learned in Leve’s workshop.

Obtaining high-quality satellite imagery is expensive for low- and middle-income countries like Nepal. Maharjan saw an opportunity for better mapping technology and spent the last six years filling that gap. His work at Galli Maps involves flying drones and driving motorbikes around Nepal, a few acres at a time, capturing images to build 2D maps.

“What we’re doing will be very important in the next 100 to 1,000 years to come,” Maharjan says.

Maharjan is passionate about Leve’s project and determined to provide engineer-grade information and blueprints for heritage sites. He describes a 300-year-old temple built by the king Pratap Malla that was destroyed in the 2015 earthquake.

“It was because of a painting we found that we could attempt to reconstruct the property in its original form,” Maharjan details.

That’s why these models, which are accurate within one millimeter, change the reconstruction game for Nepal.

“Raj had the technical vision,” Leve says. “And with Jim’s help we’ve really upped our game. Because I don’t have the technical knowledge, the computing knowledge, or the engineering knowledge.”

Heritage-preserving tech

Mahaney was drawn to the project in 2021 after reading an article about the start of Leve’s work with Maharjan and other Nepalese locals. He was confident that a laser-scan technology called LiDAR could provide her team with more advanced results.

“‘I had to figure out if I could be part of this — to go to Nepal and do work,” Mahaney says. “I mean, who gets to do that right? It’s once-in-a-lifetime type stuff.”

Mahaney has worked with laser-scan technology since 1997, when he first started at UNC-Chapel Hill as a staff member in their computer science department. He helped the university develop one of the earliest versions of a LiDAR scanner.

In fall 2024, Mahaney traveled to Nepal with Leve. They spent the first half of their 10-day trip training students in LiDAR and negotiating access to parts of Swayambhu.

The 10-person team began their documentation by dividing the temple into four quadrants. One group would move around the temple, shooting thousands of photographs of different parts of Swayambhu’s main building. Another worked with Mahaney to take LiDAR scans of the site.

They finished each day with roughly 20 scans and about 2,000 photos. Mahaney left Nepal with nearly 100 scans and over 10,000 DSLR and drone images.

Slightly larger than a human head, the advanced LiDAR scanner includes a sealed housing with a laser inside and a rotating mirror that sits on the outside of the device. The laser fires hundreds of thousands of pulses per second, reflecting off the mirror and onto surrounding surfaces, and then back to the scanner.

The time it takes to do this determines each point’s distance from the scanner. The points are then combined into a 3D model called a point cloud.

But, if the device moves during the scan, Mahaney must start the process over again. And when weather conditions change or it records movement, the editing process — which involves merging thousands of images from drones, DSLR cameras, and laser-scans — becomes incredibly difficult.

“If I was just modeling one room, for example, it would be just a few scans and a couple hundred photos — and that’s just a lot less data for the computer to process,” Mahaney explains. “To complete Swayambhu, we will have hundreds of scans and tens of thousands of photos.”

Cultural conversations

While Leve has pivoted to learn photogrammetry and LiDAR, she continues to interview stakeholders and record their stories, unique knowledge, and memories of the temple — what preservation experts call “intangible heritage.” This includes training local partners in best practices for interviewing.

Ranging from 20 minutes to three hours in length, these conversations allow Leve, Maharjan, and volunteer researchers associated with Baakhan Nyine waa — or “Come Hear Stories,” a community-based non-profit formed by several members of Rebuild Kasthamandap — to talk with key temple stakeholders about religion and culture as they manifest at the site.

The goal is to make space for what the stakeholders believe is exciting or important. Instead of using a standard set of questions, they keep the flow of conversation natural, letting it take them where the interviewees want it to go.

“We really tried to be as omnivorous and as diverse as possible in who we selected for interviews,” Leve says.

Leve recalls interviewing a skilled metalworker whose family has created and maintained statues for temples like Swayambhu for several generations.

“We asked him about growing up and learning the artwork. We asked him about the ways that the economy has changed between his great grandfather’s time and his time. What does it mean to the artist who creates the statues for temples?” Leve asks.

Leve and Mahaney plan to reunite with their partners later this year to continue their work in Nepal.

Eventually, Leve hopes to create a Nepalese organization that keeps the archival and technical work going and provide opportunities for Carolina undergraduates to travel to Nepal to contribute to the project.

“My grandfather told me that his grandfather planted a tree when he was 6 or 7 years old,” Maharjan explains. “You plant the tree without the expectation it will give you a shadow in your lifetime, but that it will give the shadow to generations to come. And we’re following the same principle for this project.”