A young girl in blue-and-white-striped pajamas wakes from sleep, startled. She hears voices — two of them — coming from each side of her bed. They talk over her and, eventually, pull the cover from her head. She opens her eyes to find a woman dressed toe to neck in an electric pink dress. The woman’s head is covered in long, soft blue curly hair. In her hand, she wields a tray of colorful cupcakes.

On the other side of the young girl sits a woman draped in a gown bedecked with silver sequins, her hair straight and bright white. Within minutes, a slew of animated objects fill the room: a life-size teddy bear, gummy candy, ice cream cones, more cupcakes — and a chorus of silver-clad women. Everyone is singing.

This isn’t a Katy Perry video. It’s an opera — and a sneak peek into the mind of UNC Opera Director Marc Callahan.

In Fall 2019, Callahan combined “Il sogno di Scipione,” an opera written by Mozart and based on Cicero’s essay “The Dream of Scipio,” with the 50th anniversary of the moon landing. His reinterpretation, called “Scipio’s Dream,” was inspired by early 20th-century absurdist artists like Rene Margritte and the retro-futuristic trends of the 1960s.

“Weird things happen in our dreams all the time. Things we can’t make sense of,” Callahan says. “This show allowed me to undo the boundaries I give myself so frequently in opera and explore some real absurdism.”

Callahan’s productions aren’t always so wild. But they are always colorful, unique, and well-researched — and they often tackle modern-day social issues in a creative, meaningful way.

“I want to train my singers the way I wish I would have been trained when I was in school, which is to see opera as a holistic process where the story informs the design, informs the direction, informs the lighting, informs every aspect of the show,” Callahan says. “I want them to see beyond their individual roles, beyond singers. They could also be a director or a designer — or both.”

A maestro of ingenuity

When tasked with producing an opera, Callahan takes a deep dive into the piece, researching its origin and past performances.

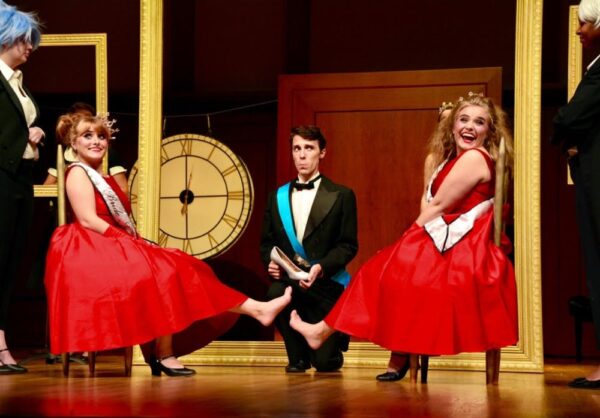

Cinderella’s stepsisters both vie for the chance to try on Cinderella’s shoe, held by Prince Charming, in Callahan’s Fall 2017 production of “Cendrillon.” (photo courtesy of Marc Callahan)

For Jules Émile Frédéric Massenet’s “Cendrillon,” which translates to “Cinderella,” he considered putting his actors in costumes and sets inspired by the 1800s, the era in which Massenet composed the opera. But that wasn’t within the budget he was working with. So, instead, he used minimalist sets and 1950s-inspired costumes.

“When you’re the director, the set and costume designer, and the builder, experience has taught me that both minimalism and mid-century modern are efficient and effective styles for almost any production,” Callahan shares.

He searched for inspiration in movies like “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes,” particularly Marilyn Monroe’s iconic performance of “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend.” He also had his students watch several big numbers from old Hollywood musicals to get a feel for the style he was looking for.

The 2017 production — and Callahan’s first for UNC Opera — snagged him a national semi-finalist position for The American Prize in Directing, which recognizes outstanding stage directors of theater, musical theater, and opera.

In 2019, Callahan took on Kurt Weill’s “One Who Says Yes,” which is based on the Japanese play “Taniko.” Prior to rehearsals, he traveled to Japan to learn about Noh theatre — a traditional performance style that dates back to the 14th century. While abroad, Callahan studied under Noh actor Shingo Katayama and met dance master Umekawa Ichinosuke, both of whom who came back to UNC with him to not only perform in the production, but to help Callahan’s students perfect his choreography.

Callahan performs a Japanese dance called a shimae while participating in the Noh play “Astumori” in Kyoto, Japan. (photo courtesy of Marc Callahan)

“Throughout the semester, the students became impassioned with this ancient form of theater — from learning to work with traditional Kanze Noh fans to understanding Noh’s important historical link to western theater,” Callahan says. “I saw how it inspired not just their passion for opera, but a passion for global art forms and an understanding of global histories. It was exciting for me to see that opera could do that for them.”

Two students became so inspired, they traveled to Japan to learn more about the culture’s performance art — and that curiosity for the world is exactly what Callahan hopes to instill. The performance also won first prize in the National Opera Association’s opera production competition, a coveted prize among top U.S. universities.

Dramatic designers

“Scipio’s Dream” marked Callahan’s first opera in which he truly pushed his students to make the performance their own. To prepare them for the production, he teamed up with staff at the Ackland Art Museum to create lessons on absurdism, surrealism, and how to tell stories through art. He also instructed his students to peruse old fashion editorials, take note of the art style in cartoons like “The Jetsons,” and watch Katy Perry videos.

“Those are all quite retro-futuristic and a little absurdist — and that was the world I wanted to create for them to inhabit,” Callahan says.

After he assigned the students their parts, Callahan asked them to sketch their props and costumes. Then, he brought them to the BeAM makerspace, where they either created them from scratch or tailored and modified purchased pieces.

“With ‘Scipio’s Dream,’ I wanted to take them one step further into seeing themselves as designers and makers,” Callahan says.

And with his current production, Callahan takes them even deeper, beyond singing and aesthetic and into a world of sound and storytelling.

Boundary-crossing arias

Callahan drives down an open road, windows down, music blasting. He’s not jamming out to classic rock or the latest hip-hop track. He’s listening to Meredith Monk’s “Atlas,” an opera written in 1991 that uses wordless vocal sounds with brief interjections of spoken text in Mandarin Chinese and English.

“While listening, all of a sudden, I would feel these waves of joy or waves of sadness,” Callahan recalls. “I’d literally be crying in my car because I’d start to imagine what this story could be.”

In his mind, Callahan pictured a boy, his dog, and his family as they make the journey from Latin America to the United States. He felt that Monk’s compositions — loosely based on the life and writings of explorer Alexandra David-Neel, who believed “travel is a metaphor for spiritual quest” — could address the controversial and painful experiences of migrants at the U.S.-Mexico border.

“Normally, when I work on an opera, the story is already there,” Callahan explains. “I might cut it down, but the story is the story. With this one, I needed to make a clear story for the audience while working with no text. As I went to do this, I knew I needed a team of people that could help me responsibly research what it means to take these journeys, and what it means to be an immigrant.”

To learn more, Callahan reached out to staff at the Carolina Latinx Center and UndocuCarolina, which strive to increase visibility, support, and resources for Carolina community members who are affected by lack of documentation. He also watched documentary films, read news articles, and collaborated with Susan Harbage Page, a women’s and gender studies professor who has spent the last decade photographing objects left behind by immigrants at the U.S.-Mexico border.

The conversations Callahan had surrounding this topic encouraged him to think about humanity and what it means to help others. While conceptualizing how the production would be performed, Callahan stumbled upon a local puppet pop-up run by Tarish Pipkins and Arts Everywhere. He knew immediately that he wanted to use puppets instead of live actors for the roles of the boy and the dog to tell the story he was crafting for “Atlas.”

“A puppet by itself is inanimate, but if we as a community help it live, if we as actors help it live, that’s basically the only way it survives,” Callahan says. “I feel the same way about the issues at the border. We have to make a choice. It’s up to us to make sure we’re all animated. That we take care of and breathe life into each other.”

What makes “Atlas” truly unique, though, is that it’s pure sound; there are no words sung in the show. When instructing his students, Callahan focused heavily on breath work, drawing on methods from Monk herself, who came to campus to workshop with his class.

“Each breath has an intention,” Callahan shares. “It was a new way of learning and of vocal expression for many of us. It tested the boundaries of our creativity and our emotions.”

Callahan’s version of “Atlas” is slated to take place once theaters can accommodate audiences or an alternative medium can be found.

“I hope my students — and others — can see that opera doesn’t belong in any one place. It’s doesn’t just belong somewhere like the Metropolitan Opera,” he says. “It can belong in dreams. It can belong in the Asian studies department. It can belong at the border. It’s an art form that touches many facets of life.”