The Institute of Marine Sciences (IMS) began in 1947 as the Institute of Fisheries Research. In the 1960s, to meet the changing needs of research, it was renamed the Institute of Marine Sciences. Today, the institute’s mission is to serve the state and the nation by conducting cutting-edge research, training young scientists, providing expertise to governmental agencies and industry, and promoting new knowledge to inform public policy.

IMS will celebrate its 70th anniversary with a community open house on Saturday, October 21, from 1 to 4 p.m. at its Morehead City location. The free event will feature tours, scientific demonstrations, and activities for children.

The Institute of Marine Sciences is a field site location for undergraduate students at UNC-Chapel Hill. The program, run through the Institute for the Environment, allows students to spend a full semester immersed in hands-on research experience. Here, Carolina undergrad Kayla Pehl sets traps for her fisheries ecology experiments.

Students and technicians from the Fodrie lab study oyster reefs in the Rachel Carson Reserve on a chilly February morning. The waterfront location of IMS affords researchers year-round access to important study sites. In addition to playing a vital role in the health of marsh ecosystems, oysters contribute millions of dollars to North Carolina’s coastal economy every year.

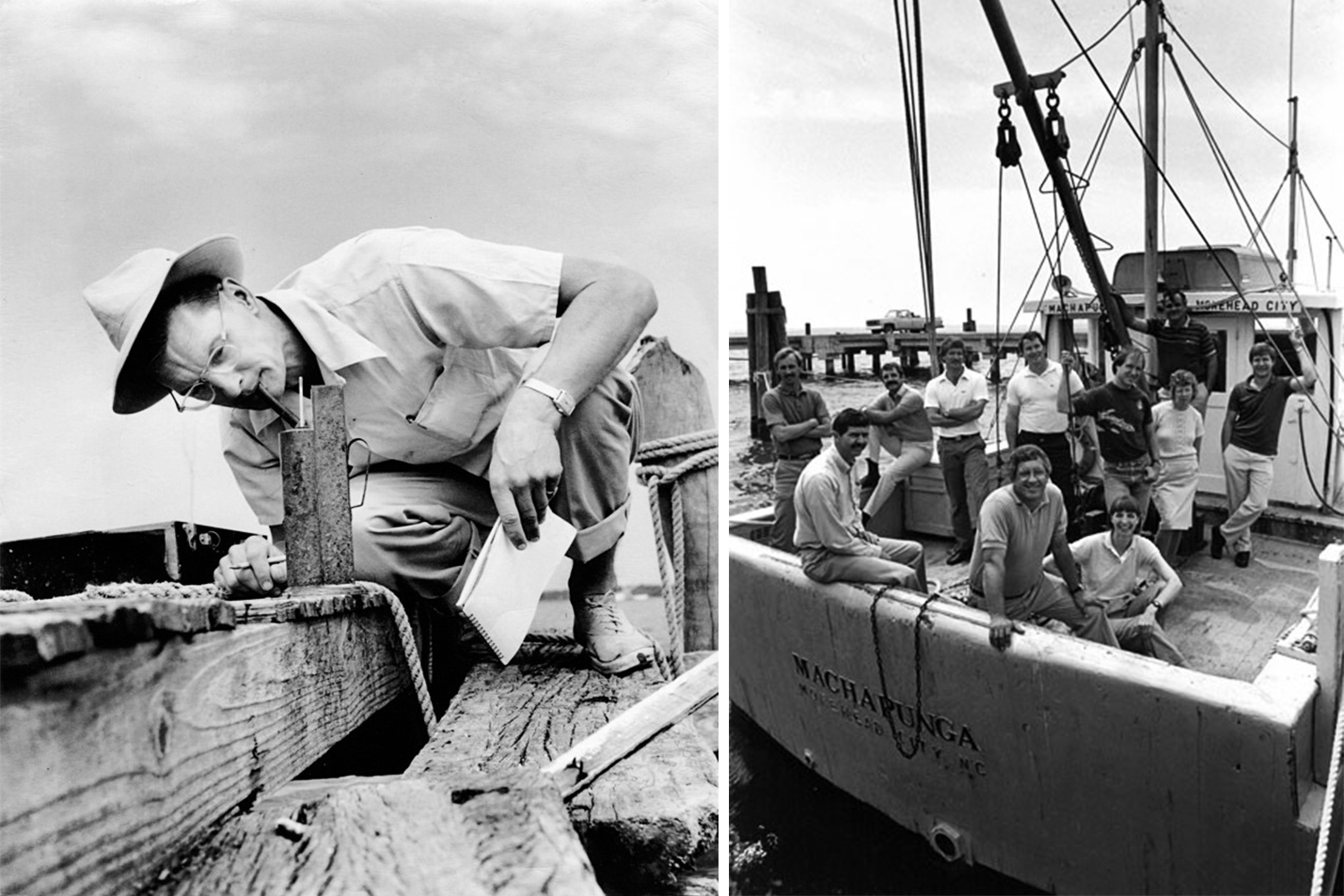

Left: Al Chestnut, director of UNC IMS in the 1960s. Chestnut was the director for more than 25 years.

Right: The research vessel Machapunga — the second research vessel at IMS.

Emily Pickering photographs a juvenile loggerhead sea turtle before releasing the rehabilitated turtles back into the Gulf Stream. The institute is proud to assist local agencies that respond to and rehabilitate sea turtles. Park rangers find the turtles and transfer them to aquariums where they spend one to three months in rehabilitation. When the turtles are healthy again, researchers transport them to the warm waters of the Gulf Stream.

Peterson lab PhD student Avery Paxton uses her SCUBA training to study the reefs of North Carolina. Here, she works at a depth of about 100 feet off of Cape Fear, North Carolina, looking at how different types of reefs are used by fish and how that helps guide offshore wind energy development.

This aerial view shows the IMS campus in the 1940s. In 1968, a large fire destroyed many of the original buildings at the Institute.

Claude Lewis, a maintenance mechanic, carries a set of buoys to the Capricorn — the largest research vessel owned by the Institute. The professional mariners play an essential role in supporting the education and research activities at the institute.

As part of an ongoing effort to improve oyster restoration in the state, Niels Lindquist, a professor at the institute, has teamed up with a local fisherman, David “Clammerhead” Cessna, to figure out the best way to grow all-natural oysters along North Carolina’s coast.

“We want to work with commercial fishermen to develop a program where everybody benefits from growing oysters — for food markets but also for restoration and living shorelines.” He and Cessna are already working on developing partnerships with the Division of Marine Fisheries and the Coastal Federation to make this a reality.

Robert E. Coker (right), the first director of the Institute for Fisheries Research in 1947, educates fellow researchers out in the field.

Glenn Safrit swims through a school of vermillion snapper and tomtate as he comes up from a dive. As director of the IMS Dive Program, Safrit has spent the better part of three decades ensuring all IMS scientists conduct their underwater research in accordance with the standards put forth by the American Academy of Underwater Scientists. IMS became part of the AAUS in the 1990s.

The institute is home to one of the longest-running shark research programs in the nation. Here, Martín Benavides holds a shark to record its measurements before releasing it back into the water, about seven miles offshore.

The study, which runs every two weeks from April through November, also serves as a platform to allow other area researchers access to the animals. Spanning over four decades, this long-term data site provides critical information on the animals and their environment.

Rachel Noble, a professor at the institute, inspects an oyster sample in the Pamlico Sound. The Noble lab bridges environmental microbiology and marine microbial ecology, putting research to work for public health. Her lab has developed rapid testing methods to detect bacteria and viruses that may be found in water or food.

The Capricorn research vessel has served the needs of the institute since the 1980s. IMS is the only place in the state where scientists can train to become certified research divers.

The Luettich lab studies the ways in which physical processes influence how water moves in coastal systems. A cornerstone of the lab’s research is modeling storm surge impacts along the U.S. coasts, research that is used by agencies such as FEMA and the U.S. Coast Guard to make important decisions during major storm events. They are also actively developing and deploying novel instrumentation to study North Carolina waters ranging from Jordan Lake to our estuaries and sounds.

Hans Pearl, a professor at the institute, examines a water sample from the Neuse River. The Paerl lab looks at the impacts of nutrients in aquatic systems, from the Neuse River to Lake Taihu in China. In particular, they study harmful algal blooms. The lab monitors long-term health of the Pamlico Sound system, the second largest estuarine complex in the country.

Adam Gold and Suzanne Thompson, members of the Piehler lab, sample a storm water pond in Camp Lejeune. Storm water management applies a set of control measures that are designed to control water flows and reduce nutrient and sediment concentrations. Research represented in this picture has led the Piehler lab to rethink the use of storm water ponds for nitrogen reduction. Adam Gold was awarded the GEAB Impact Award for this work.

Suzanne Thompson, a technician in the Piehler lab, holds up a sediment core from a restored marsh in Jacksonville, North Carolina. This core and others like it were used in a nutrient flux experiment to understand the role that constructed marshes play in mitigating nutrient pollution.

Graduate students from the Fodrie lab work with the research coordinator of the Rachel Carson Reserve to measure different types of seagrass. Their research examines how fish habitats in estuaries might be impacted by warming waters.

The Paerl lab conducts experiments on water samples from around the world, examining the nature of toxic algae blooms under varying conditions.

Robin Kim, an undergraduate intern in the Rodriguez lab, uses a Trimble GPS to map changes in the morphology of a barrier island after a storm event.

Every February, faculty, staff, and students at the institute come together to celebrate at the annual IMS oyster roast.