On a cold New England day in mid-January, Claire Bunschoten received the email she’d been waiting for. She’d left New York City just two days prior, determined that a few weeks in New Hampshire with her husband would provide the comfort and quiet needed to wrap up her dissertation.

“It’s blooming,” the email read.

But this wasn’t supposed to happen for weeks yet.

Bunschoten responded like a person whose partner is in labor. She packed an overnight bag, stressed over finding a sitter for her dog, and hopped on the road at 5 a.m. the next morning.

After five hours of driving, she arrived at The New York Botanical Garden (NYBG) just before lunch and rushed to the conservatory, where she was greeted by dozens of schoolchildren in puffy winter coats. After strategically zigzagging through the chaos, her hair frizzy and wet from the garden’s misters, she successfully made it to the back corner of the building, braced herself, and looked up.

The not-so-ordinary vanilla orchid. (Adobe Stock)

She traced a thick green vine with her eyes, following its snaking path up a tree, about nine feet in the air. Along the way, she caught sight of several creamy, bell-shaped blooms — and immediately pulled out her phone to capture their presence.

Bunschoten, a PhD student in the Department of American studies at UNC-Chapel Hill, had been waiting months for this vanilla orchid to bloom.

“There it was all the way up there, and I can’t see it, and the zoom on my phone is garbage,” she says with a laugh. “It was kind of anti-climactic, but also very humorous. Like, Here we are! The moment has come! It was just cool to be there after reading about this plant for so long.”

Bunschoten first arrived at NYBG in the fall of 2022 as part of their nine month-long, residential Mellon Research Fellowship. For the first time, the program is hosting food studies scholars, giving them access to the garden’s archives, library, and herbarium to conduct their research.

For the last three years, Bunschoten has immersed herself in the world of vanilla — from the flavor to the fragrance to the 1990s rapper Vanilla Ice. Her dissertation unpacks the spice’s history and provides a unique lens for addressing culture in America.

“I’m interested in the ordinary things we take for granted — and how those tell powerful stories about life in the U.S.,” Bunschoten explains.

From nature to the lab

When Bunschoten reflects on the impact vanilla has had on her life, she’s overcome with sensory impressions. Those tiny vanilla ice cream cups that came with a wooden spatula-spoon. Vanilla-flavored BonBons lip gloss. And the post-gym class locker room spritz of Bath & Body Work’s “warm vanilla sugar” body spray — so much that clouds of the stuff filled the air.

Today, only 2% of U.S. products that use vanilla as a flavor or fragrance contain extracts from the actual vanilla bean. The other 98% use synthetic formulations. Bunschoten challenges the natural-artificial dichotomy.

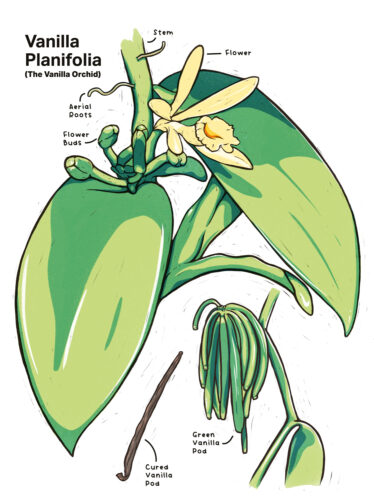

An illustration of the vanilla orchid and its various parts. (illustration by Corina Prassos)

“There is a common theme in food studies about this idea of ‘natural’ and the way that is prized,” Bunschoten says. “Hand over fist, one of the most important things food can be is natural. And yet, if we really break it down, it’s not. I don’t think anything about vanilla is particularly natural if we think about the different steps that go into creating one vanilla bean.”

Bunschoten looks back to the mid-1800s, when vanilla was only available as a bean and incredibly expensive. Extreme patience is required for cultivating vanilla. Besides the fact that the sap from the stems can cause moderate to severe dermatitis, each flower opens for just 24 hours and the plant must be hand-pollinated at this time to produce a vanilla bean. It takes about nine months for fruit pods to fully mature. Once they do, they are collected and cured — a fermentation and drying process that helps the pods develop the sweet, creamy aroma folks are so fond of.

The vanilla orchid is native to Mesoamerica and grows best along the equator in hot and wet tropical climates, meaning it had to be sourced from those places hundreds of years ago. As it grew in popularity during the 19th century, chemists begin experimenting to create an extract of vanilla beans suspended in alcohol. While this improved accessibility and slightly lowered the cost, it wasn’t enough. The demand became high enough that they looked to other flavors to mimic vanilla — balsam, tonka beans, prunes, and dates. In Germany, vanillin, a chemically derived vanilla, was invented.

Ice, ice baby

In her dissertation, Bunschoten argues that vanilla holds multiple cultural meanings. Vanilla is anything but plain. It shapes numerous moments across lives, politics, and culture.

At the turn of the 20th century, the government enacted the Food and Drug Act of 1906 to regulate the federal standard for vanilla extract, stating it can only contain vanilla beans and must be labeled as such. Taste-testers traveled across the country to enforce companies to adhere to this regulation.

In the 1920s, as it continued to grow in scrutiny and popularity, new versions of vanilla emerged. It was referenced in songs, movies, and newspapers — and even a boxing match review. The term “plain vanilla” appeared.

“I’m trying to find that moment when vanilla becomes so familiar it takes on all these other meanings,” Bunschoten shares.

“It is the vanilla bean, the clear imitation of flavoring on sale at convenience stores, and the condemnation of the ordinary by calling something ‘vanilla.’ It is all of this and more,” she writes. “New forms of vanilla constantly inflect the nation’s ever shifting sensorial kaleidoscope. Yet, they are all somehow familiar and understood.”

To delve into this complexity beyond flavor and fragrance, Bunschoten argues that vanilla is a euphemism for race through a case study on Robert Matthew Van Winkle, who’s more commonly referred to as “Vanilla Ice,” the rapper from the 1980s and ’90s known for the hit song “Ice, Ice Baby.”

“He is such a complicated and weird cultural figure — a delight but also boggling,” Bunschoten shares.

Van Winkle’s identity as a rapper is both “created and culturally condemned by Black Americans,” according to Bunschoten. His career is often symbolized in the same way vanilla is depicted across American culture — as basic and lacking — but Bunschoten argues his story suggests that vanilla is as complex as race.

Van Winkle’s friends began calling him “Vanilla” in middle school. While he hated the nickname then, it became the crux of his act as a performer later on. He began rapping and dancing in Black clubs across Dallas and grew in popularity, partially because he stuck out in those spaces.

“At that time, being called ‘Vanilla’ was a good thing,” Bunschoten says. “But by the time he hit national attention, there was a lot of buzz and assumptions that his popularity was driven by his whiteness, which he was always trying to push back on but, ultimately, couldn’t outrun.”

A menagerie of resources

While the New York Botanical Garden is probably best known for its stunning, glass-domed conservatory, it’s also home to the LuEsther T. Mertz Library — the largest botanical research library in the Western Hemisphere. Within the walls of this 122-year-old Renaissance Revival style building, Bunschoten has discovered a treasure trove of materials for her research.

“They have these astounding botanical histories and texts from all over the world,” she shares. “So it’s figuring out how I can think with those texts in my own research.”

A few of the “tiny delights” she’s discovered include historic illustrations of the vanilla orchid and herbarium specimens that are more than 150 years old. To her surprise, the garden also has a collection of ingredient-specific cookbooks, including a few on vanilla.

The NYBG’s LuEsther T. Mertz Library is the largest botanical research library in the Western Hemisphere and has greatly aided Bunschoten’s research. (photo by Marlon Co, The New York Botanical Garden)

“One from the 1960s is called ‘The Romantic Story of Vanilla.’ The authors replaced the ells in ‘vanilla’ with two vanilla bean pods,” she says with a laugh. “It was a creative choice. Some of these books are very funny.”

Another cookbook details how to do a proper vanilla tasting with friends: Pour milk into shot glasses and add a few drops of vanilla to each one.

Additionally, NYBG has two women on staff who Bunschoten calls “plant hotline specialists.”

“They are librarians of growing plants,” she says.

In talks with them, Bunschoten began thinking about what it would involve to grow a vanilla orchid in your apartment. And that sent her down a rabbit hole of questions: Who is growing a vanilla orchid in their house? And why would they do that?

Today, it is primarily harvested in Mexico, Tahiti, Indonesia, and Madagascar. The orchid itself has both ground and aerial roots, and it needs to grow about 10 feet to bloom and fruit. Vanilla is the only orchid that produces edible fruit.

The fruits of Bunschoten’s labor will pay off this spring as she wraps up her PhD program at UNC-Chapel Hill. She graduates in May, her NYBG fellowship ends in June, and this fall she will start a new position as the Abbott Lowell Cummings Postdoctoral Fellow in American Material Culture at Boston University.

As she moves forward in her studies, she will continue to explore the intricacies of vanilla — including its relationship to sexuality — and hopes to grow her dissertation into a book project. She’s also interested in continuing work on another American classic that she researched in her undergraduate years: apple pie.

“I love looking at little things that tell big stories,” she reiterates. “There’s so much beauty in the ordinary, and I want to relish the time we get to spend with these flavors and fragrances. To be curious about the world and the things we interact with all the time.”