For the past 50 years, staff and scientists at the UNC Highway Safety Research Center (HSRC) have been dedicated to saving the lives of America’s teenagers, children, and adults. When the center formed in 1966, more than 50,000 Americans died in car crashes — a statistic reflective of the alarmingly low rate of seat belt use during that time. To combat the problem, HSRC develop programs like “Click it or Ticket,” as well as Graduated Drivers Licensing, a three-stage approach for granting young drivers full license privileges.

Today, both programs have been adopted nationwide and, in 2015, 88.5 percent of American drivers buckled up, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). Thanks to the HSRC — the only transportation center in the country focused solely on highway safety — being on the road today is much safer than it was 50 years ago.

Recognizing a need for highway safety

Fueled by the post-World War II economic boom, automobile production hit an all-time high in the late ’60s. Putting more cars on the road — many of them fast, high-powered vehicles (this was the era of Mustangs and Corvettes after all) with no air bags and no seat belt laws in place — created a bit of a perfect storm.

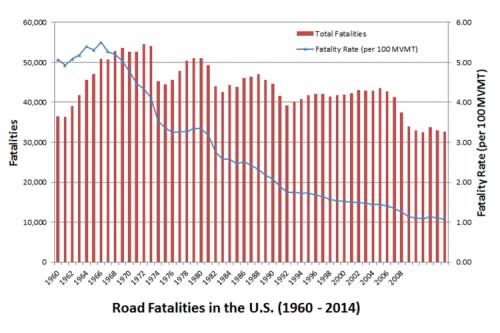

“If you look at graphs showing car crash fatalities, there is a very sharp increase in the 1960s. The number of people losing their lives on our highways was accelerating,” HSRC Director David Harkey says. “So there was a lot of emphasis from public officials on how to reduce the death toll on our roadways. That was how our center came to be.”

This HSRC-created graph shows a spike in crash fatalities during the 1960s due to a lack of seat belt safety laws.

Established the same year as NHTSA, HSRC opened its doors in 1966, thanks to a big push from North Carolina’s then-governor, Dan Moore. His campaign focused on establishing our state as a leader in highway safety — a legacy that remains strong to this day.

From the beginning, HSRC worked closely with the NC Department of Transportation and the Governor’s Highway Safety Program (GHSP). Its research drove changes to state laws and policies that were costing lives. It led to safer roadway design and traffic operations, more meaningful vehicle inspections, and advances in pedestrian and bicyclist safety.

“It’s a mutually beneficial relationship,” Don Nail, current director of North Carolina’s GHSP, says. “Working closely with HSRC has been a powerful way to expand the reach and scope of both of our individual organization’s activities and projects — all the while working toward the shared goal of improved safety on all of NC’s roadways.”

Convincing the public to buckle up

Looking at the statistics from the 1960s and ’70s, it’s no wonder people were dying — fewer than 10 percent of adults involved in crashes wore seat belts and fewer than 5 percent of children were buckled up, according to research from HSRC.

The numbers didn’t lie — lack of seat belt use was directly connected to higher rates of mortality in car crashes. As it became clear from the research that a wide range of efforts to persuade people to buckle up voluntarily were failing, HSRC recommended new laws that would push people to do the safe thing: Use a seat belt.

But instituting new laws can be complicated, and you need a logical starting point. “When it comes to making policy changes, it’s best to start with the populations that are most vulnerable within the system — like children,” Harkey says.

It was 1978 before the first U.S. child passenger safety law was passed in our neighboring state of Tennessee. North Carolina’s child passenger safety law went into effect just four years later with help from HSRC, which provided legislative sponsors with information and recommendations for provisions that should be included in the law. In 1981, only 11 percent of children under 5 involved in North Carolina crashes were buckled up, reports HSRC. By 1984, this rate increased to 33 percent. Today, nearly 95 percent of children in this age range are buckled into seat belts or car seats.

Still, that same year, only 25 percent of North Carolina adults were observed wearing seat belts and New York was the only state with a seat belt law covering people over 18 years old. In 1985, North Carolina became the sixth state to require that adults wear seat belts. Once officers started issuing warnings, belt usage increased to 40 percent. “The real difference came when the N.C. Highway Patrol and local police officers started writing tickets — subsequently belt use climbed to 81 percent,” Harkey says. “It showed we could make a difference.”

But from 1987 to 1992, the rate of seat belt use dropped back down to 65 percent. “That’s when we realized that just having the law by itself was not going to have the desired effect,” Harkey says. “We had to come up with something else.”

Telling people to buckle up wasn’t enough. And issuing tickets here and there wasn’t enough. The key was to use both approaches consistently and creatively. Working with the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety, the N.C. Department of Insurance, local law enforcement, and other partners in the state, HSRC and GHSP developed and introduced the “Click it or Ticket” campaign.

At the time, HSRC and its state partners could not use federal funds to advertise the new initiative. But partnering with the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety provided access to private money for paid advertising. “That was critical to help get the word out,” Nail says. “Public service announcements don’t really work. The beauty of paid media is placing ads when and where they are most effective in reaching target audiences. We didn’t have social media back then, but those ads were a big improvement over what we had been able to do before. It made all the difference in the world.”

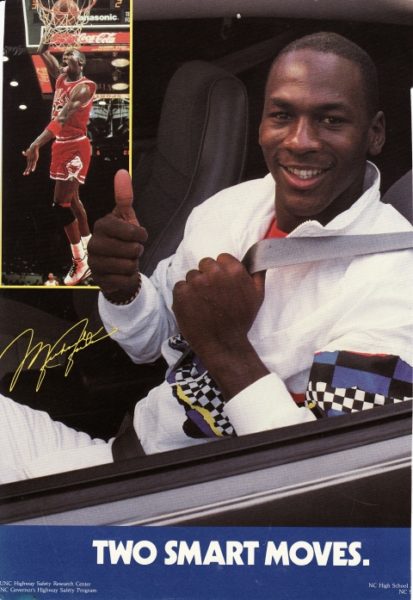

Photo couresty of UNC Highway Safety Research Center

Perhaps the most popular ad for a GHSP-funded seat belt campaign featured a young Michael Jordan. “This was back in 1988, before Jordan got so big and famous that he was inaccessible,” Bill Hall, manager of HSRC’s occupant protection program and member of the original project team, recalls. “We got him to agree to sit there in the parking lot of the Hotel Europa for five or 10 minutes.”

The heightened media attention, coupled with announcements that law enforcement would be conducting stops on Memorial Day and Labor Day, had an immediate effect — the state’s seat belt use rate climbed back up to 81 percent.

And that’s when the rest of the country started to take notice.

In 2000, South Carolina adopted the program, followed by several other states in 2001. “By 2003, 43 states had adopted ‘Click it or Ticket,’” Harkey says. “It eventually became and still is the recognized program of the National Highway Safety Administration.”

Today, North Carolina’s seat belt rate steadily hovers around 90 percent. But Harkey says he and his colleagues still face challenges in convincing the remaining 10 percent of the population to buckle up. “Seat belt use in rural areas is less than the state average and an opportunity for improvement,” he points out. Another major issue, according to HSRC data, is the lack of seat belt use at night. “It’s particularly bad late at night, when people are more likely to be driving impaired,” Harkey adds. “And if you’ve got people driving while impaired and not wearing their seat belt — well, there is certainly more work to be done.”

Learning to drive by driving

If you received your driver license in North Carolina prior to 1997, the process probably went something like this: a written test, a vision test, and a “really, really simple” driving test, according to Rob Foss, director of HSRC’s Center for the Study of Young Drivers. Back then, obtaining a permit was optional. Novice drivers could get one if they wanted to, “but it wasn’t required,” Foss says. “Essentially, you just had to pass three tests that had little to do with safe driving to get a license.

“All the evidence we have shows that people learn to drive by driving,” Foss continues. “They don’t learn by being told how to drive. They don’t learn by being told scary things about risks. They learn to drive by driving.”

HSRC researchers studied the challenge posed by unskilled teen drivers. They concluded that taking a classroom driver education course and spending six hours behind the wheel (the standard at the time) was simply not enough. “Driver education in and of itself — the way it’s still structured for the most part — doesn’t produce safe drivers,” Foss says. “This is because people learn how to do things, like drive safely, through practical experience rather than formal education.”

To ensure they got this experience, HSRC researchers came up with the idea for Graduated Driver Licensing (GDL) — a new model for driver training which entails earning a license in stages, helping beginners learn by doing while protecting them from the danger that results from their lack of experience.

The first stage of a GDL program is a learner license — a one-year program that allows a young or novice driver to drive with an adult licensed driver in the car. An experienced driver in the car discourages impulsiveness and helps the new driver avoid dangerous mistakes that cause crashes, according to researchers.

“But there are some things you just can’t learn with mom or dad in the car,” Foss says. “You can’t learn self-control. You can’t learn to control your passengers. You can’t learn to make all the decisions on your own because you’ve got the co-pilot there — so eventually you have to start driving on your own.”

During the second stage, a young driver can drive independently, but with restrictions — only one passenger in the car and not after 9 p.m. “The reasons for both of these restrictions is that research shows they are risky conditions,” Foss says.

The best hour at which to restrict teen driving is 9 p.m., but some states set the hour as late as midnight. “Most states have gotten GDL wrong by setting the night limit at midnight, thinking it’s a curfew,” Foss says. “It has nothing to do with curfew, though. It has to do with avoiding the riskiest driving conditions out there while you’re still a beginner driver.”

After completing a six-month intermediate license period (with no tickets and no crashes), a young driver can finally get a full license. It used to take one day to get a license. Now, it takes at least a-year-and-a-half.

“It’s worth the extra time and effort because it works,” Foss says. HSRC has collected data from multiple states, but its most extensive data comes from North Carolina. It shows a 38 percent decrease in crash rates among 16-year-olds following the state’s enactment of its GDL program.

Since GDL began in 1997, HSRC staff have continually evaluated and reevaluated the program. North Carolina and Michigan were the first states in the country to implement it. “Since then, we’ve probably worked with close to 20 other states to help them understand GDL and develop their own licensing systems,” Foss says.

Looking across the country and to the future

With the spread of both the “Click It or Ticket” and GDL programs, HSRC and UNC have helped change America’s driving behavior. “HSRC is well recognized as a leader across the nation,” Nail says. “They are always behind the scenes, but they play a huge role in making better policies for our state and the country.”

Despite HSRC’s success over the past 50 years, an enormous amount of work remains to be done. “You’ll notice that traffic deaths are not yet zero. Teen driver crashes are down, fatal crashes are down, but there are still a lot of people getting hurt and killed out on our roads,” Foss says. “We haven’t solved the problem — we’ve just made a big dent in it.

“The world changes,” he adds, and points to the most apparent hazard on the roads today. “Twenty years ago, no one was driving around with a phone pressed against their ear — or looking at a screen. New risks pop up and need to be understood.” That need to understand both human behavior and the risks it poses lie at the core of HSRC’s mission.