Last March, life was good for Cynthia Smudde. Financially independent, the 19-year-old was a supervisor at Starbucks, working her way into their education program to help fund her college tuition. Her dream was to obtain a degree in computer science and work as a software developer for the U.S. Department of Defense.

Then COVID-19 spread throughout the United States.

Although young and healthy, Smudde was still worried about contracting the disease — not much was known about the virus, and her job involved interacting with the public.

“The media kept blasting us with all this scary news but I had to work and I had to lead people,” she says. “So I was trying to keep morale up and suppress any fears I had about it.”

At the time, there were no statewide stay-at-home orders or mask mandates where Smudde lives in Virginia. The first week of March, she fell ill. She experienced a fever and chills. She couldn’t keep her eyes open for more than 45 minutes at a time.

“I remember thinking, If this is COVID, no wonder it kills grandparents because this is the most sick I’ve ever felt in my life,” she says. “I literally felt it in my whole body. It took everything in me to fight it. I was so tired.”

Smudde contacted her doctor, but she was told it wasn’t COVID-19 because she didn’t have a cough. That also disqualified her from getting a SARS-CoV-2 test.

Within a week, her symptoms subsided and she returned to work. About two weeks later though, Smudde noticed her memory was shoddy and she was always tired. At the time, she didn’t think much of it, but soon her symptoms snowballed.

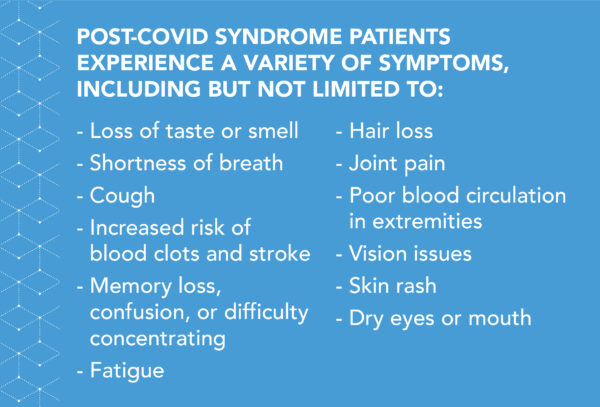

She continues to experience extreme fatigue, confusion, and memory loss — sometimes so bad she forgets where she is or learns something new and has no memory of it the next day. Her lungs sometimes feel like they are on fire or full of shards of broken glass. Initially, Smudde attributed this to mold in her apartment, so she moved. But breathing problems persisted, on and off. She was losing so much hair she needed to unclog her shower drain every few weeks. She’ll suddenly feel dizzy, as though she’s about to pass out. She’s lost her taste and smell for bouts of time. She’s experienced dry eyes and poor vision, body trembling, arthritis-like pain in her joints, skin rash, and waves of chills, heat, and nausea.

Smudde has symptoms of post-acute sequelae of SARS-CoV-2 infection, commonly called post-COVID syndrome or long COVID, in which patients endure continued effects of their infection. Like SARS-CoV-2, long COVID is also novel, and experts are still working to define it. Some consider patients to have the the syndrome if they continue to have symptoms four to six weeks after their initial infection resolves; others say 12 weeks. While most common in those who have been hospitalized with an acute illness, long COVID can occur even in people who have a mild case of the disease.

“The majority of COVID patients, I believe, have a full recovery without lasting effects,” says John M. Baratta, UNC assistant professor of physical medicine and rehabilitation. “But, there is a surprisingly large percentage of survivors who deal with ongoing issues.”

That’s why Baratta has helped start the UNC COVID Recovery Clinic — where patients can get help for their ongoing symptoms and doctors can gather valuable data.

“We don’t have a lot of specific, scientific answers because it’s just all so new,” Baratta says. “Through research, that’s what we and others have to figure out.”

Exploring the syndrome

A study recently published in “The Lancet” followed over 1,700 COVID-19 patients discharged from the Jin Yin-tan Hospital in Wuhan, China in 2020. Six months after their infection, 63 percent experienced fatigue or muscle weakness, 26 percent had sleep difficulties, and 23 percent reported anxiety or depression.

Surveys in France, the Faroe Islands, and Switzerland revealed that 35 to 54 percent of patients with mild acute COVID-19 had persistent symptoms two to four months after infection. And 50 to 76 percent reported either new symptoms not present during their COVID-19 infection, or ones that resolved and then reappeared.

In the U.S., where thus far over 28 million people have been diagnosed with COVID-19, 10 to 30 percent — up to 8.4 million people — experience continued health issues.

While researchers are still exploring the cause of long COVID, one theory says symptoms are due to the damage caused by the infection and subsequent inflammatory response.

For example, fighting an acute case of COVID-19 can lead to increased levels of the protein cytokine in the bloodstream — called a cytokine storm — which tells the immune system, Get to work. While helpful in controlling the growth and activity of immune system and blood cells, it can also cause coagulation. Some think this blood thickening may also be the reason behind “brain fog.” It’s not that the brain is damaged during COVID-19, but rather there is an issue with blood flow due to the cytokine storm.

While the Wuhan study has shed some light on the pervasiveness of the condition, there is still a mountain of unknowns. Those unknowns may have contributed to Smudde’s struggle to get help from doctors. She has seen 19 specialists over the course of the past year, but says most are dismissive. Since she was never able to get a COVID test while sick, and her first antibody test wasn’t until November, many don’t attribute her poor health to post-COVID syndrome.

“Most of them don’t believe me. For four months, one doctor kept telling me that she thought it was just stress,” Smudde explains. “I just need help. Sometimes I feel like I want to scream. I need someone to help me because I can’t do this alone.”

Treating the whole patient

While health care workers have noticed an increasing number of “COVID-19 long haulers” over the past year, keeping track of these patients has been difficult.

“People with these symptoms were kind of getting scattered throughout the health system,” Baratta explains. “A lot of them were following up with their primary care doctors, but since there hadn’t been a coordinated effort to help manage these patients, there wasn’t a lot of knowledge about what could be done to get them the care they needed.”

It became apparent that this was more than an anomaly. This fall, talks began about developing a clinic specializing in helping people with long COVID, and thus, the UNC COVID Recovery Clinic was born.

While currently accepting internal referrals for initial visits, Baratta, now the co-medical director of the clinic, expects it will be fully operational this May. Using telemedicine and in-person appointments, patients will be assessed by a team of specialists from a variety of disciplines. Care will be coordinated through the UNC Medical Center and the patients’ primary care provider.

John M. Baratta and Louise King are co-medical directors of the UNC COVID Recovery Clinic (photo by Megan May).

“Since this affects so many different organ systems we wanted to include a number of different relevant departments within the school of medicine, so this really turned out to be a great collaborative effort,” he says.

That collaboration includes specialists from UNC rehabilitation medicine, cardiology, pulmonology, nephrology, neurology, psychiatry, neurophysiology, nutrition, and occupational, physical, and speech therapy.

Not only is it important to address physical symptoms, but also the mental-health effects from enduring COVID-19. “A lot of people are having mental-health issues and I think that’s an important overlap with this, too. People who have anxiety, depression, or PTSD related to the illness may be slower to recover,” Baratta says.

When a patient is admitted into the clinic, they will have a telehealth appointment to address their needs. After the initial evaluation, they will then be referred to different specialists for additional assessments depending on their medical issues.

“I think there is a lot of fear associated with a COVID diagnosis and post-COVID symptoms,” says Louise King, an assistant professor in the UNC Department of Medicine and co-medical director of the clinic. “If we can help reassure and treat people it would be a huge benefit to them.”

Not only will the clinic provide much-needed care to COVID-19 survivors, but it can also serve as an opportunity to learn more about the syndrome.

Informing further research

A challenge with long COVID is that it has been difficult for researchers to gather consistent data — once patients leave the hospital and return to their primary care doctors, they fall off the map, so to speak. The UNC COVID Recovery Clinic hopes to help resolve this problem.

“Any information, any clinical research that we can do will be valuable because there’s so much unknown,” King says.

Working with the North Carolina Translational and Clinical Sciences Institute — which specializes in helping researchers through the process of clinical trials, regulatory approval, and data gathering and analysis — the team is creating a database that will collect patient information. They are also enlisting the help of the UNC Department of Infectious Diseases, which has a wealth of knowledge following cohorts over long periods of time.

The data will focus on a patient’s experience with COVID-19, symptoms during and after infection, pre-existing medical conditions, and demographic information. While the release of this data is dependent on the patient’s consent, Baratta is confident many will be willing to help.

“A lot of people are invested in helping society overcome this issue, particularly the survivors,” he says.

For Smudde, post-COVID syndrome has been more than a nuisance — it’s affected every area of her life. In November, she took leave from her job and consequently might lose funding for school. Without work, unemployment, or disability assistance, she’s had a hard time paying her bills.

She has, though, made some progress in her fight. Long hauler groups on social media have been helpful, giving advice on how to be your own advocate in the doctor’s office, and supplements that can help ease symptoms. She’s completely changed her diet and practices Pilates and meditation. She’s supported and uplifted by her friends and church community. Unfortunately, though, she still has a long way to go and sees medical treatment as the main driver in her recovery.

“I think if I could get into a clinic I could get back to work and start working on my degree again. That would mean the world to me,” she says. “I believe in my ability to get better. I just refuse to give up. But if I could get help from doctors I feel like I wouldn’t be on my own. Like, finally, people who knew what they were doing and I’d be believed.”