When most people think of research, they often imagine scientists running around a lab filled with high-tech equipment, their white lab coats flapping behind them. But most scholarship happens behind a computer, as researchers analyze data, compose journal articles, connect with colleagues, apply for funding — and occasionally work on a book project.

Researchers are detectives, digging through archives to explore the past, interviewing people about their experiences, and asking the big questions that their readers want answered.

But what goes into a project of this magnitude?

Five faculty authors from across campus discuss their recent book projects, sharing their inspiration, approach, and advice for aspiring authors.

Balancing the scales for Black student loan borrowers

photo by Megan Mendenhall

photo by Megan Mendenhall Fenaba Addo is an associate professor in the Department of Public Policy within the UNC College of Arts and Sciences. Her book, “A Dream Defaulted: The Student Loan Crisis Among Black Borrowers,” released in November 2022.

Provide a short synopsis of your book.

The book explores how Black student loan borrowers progress through college — and how the hardships they experience and the types of colleges they attend leave them with no choice but to borrow and keep borrowing to stay in school.

We then discuss what happens once these students leave college and start repaying their loans. We consider the consequences of educational debt for economic, psychological, and social wellbeing; show how student loan debt has made the transition to adulthood more fragile and precarious for Black youth; and explore the consequences of rising student loan debt for intergenerational inequality.

What inspired you to write this book?

My co-author Jason Houle and I worked on this topic separately and together for many years. We realized that we had so much to say, and the journal article format — which is usually 35 to 45 pages — restricted our ability to expand on the topic. Often reviewers would comment that we were trying to cover too much and needed to streamline our papers. A lot of our cut passages ended up in the book.

To complement our quantitative analysis, our editor recommended speaking with borrowers. After speaking with them, we realized how important and necessary their stories were to the book.

What kind of research went into this project?

Using a combination of quantitative academic research and qualitative data from interviews with nearly 50 Black student loan borrowers, all of whom attended four-year colleges and universities, we examined the structural factors that contribute to Black young adults having some of the largest outstanding accumulated student debt and highest rates of default and delinquency.

We also investigated how long-standing racial inequalities in parents’ wealth, education, and income exacerbate Black students’ need to borrow for college and complicate their transition to college.

How has writing this book changed how you view or approach your research?

Writing a book was a massive, but fun, undertaking. I never let being a scholar who does not come from a book-focused field limit me. I considered all the audiences we might be able to reach beyond academia and was eager to delve deeper into a topic that had come to define my research agenda.

I am lucky to have an amazing coauthor with whom I work very well. We capitalized on our comparative advantages, and I believe that was what made the process flow.

Any advice for aspiring book authors?

Timing is everything. I think successfully completed this book because we were both at a stage in our careers where a book-length treatment of our research became the logical next step for us to contribute to the student debt conversation. I strongly believed in this project and was ready to advocate for it when internal and external roadblocks, indecision, and fear surfaced. I recommend assessing how and when you want to enter the conversation of your next big research idea and gauge whether a book will allow you to meet those goals.

Digging up the dirt in digital advertising

photo by Megan Mendenhall

photo by Megan Mendenhall Lee McGuigan is an assistant professor in the UNC Hussman School of Journalism and Media. His book, “Selling the American People: Advertising, Optimization, and the Origins of Adtech,” released in July 2023.

Provide a short synopsis of your book.

My book explains how the advertising industry learned to dream of optimization and speak in the idiom of management science. That process got going in the 1950s and 1960s when certain marketers became fascinated with the potential for computers and mathematical models to help them increase the efficiency and speed of their business.

Their efforts to predict and influence consumer behavior and package and sell audience attention helped channel and amplify currents in surveillance, information technology, and behavioral and management sciences. Those developments led to the emergence of what is now known as “adtech.”

Adtech is a circulatory system for money and data online. It’s a collection of databases and automated, algorithmic systems that make predictions and bets about the value of consumers and their moments of attention or behavior. It determines what ads people see and how revenue flows to websites, apps, and content creators. And it’s a central element of what some people call “surveillance capitalism,” which has become a major talking point in public debates about the social implications of digital services like Google and Meta.

What inspired you to write this book?

I’ve always had an interest in advertising and marketing, media, technology, and consumer culture. Over the past 10 years, I’ve studied the contemporary cable television industry and its efforts to match the capabilities attributed to internet advertising. I kept a close eye on spaces where the industry assembled to talk about itself — like trade publications and professional gatherings — and noticed that people expressed various hopes and anxieties about new technology.

I’m also interested in the history and political economy of commercial media and began tracing these hopes and anxieties back in time to see how advertising and media industries coped with the promise and perils of new technologies in the past. I found that the discourses being used to promote adtech in the present had some profound resemblances to the dramas staged half a century ago to animate the power of computers and management sciences in advertising.

What kind of research went into this project?

I conducted archival research, read old trade publications, and interviewed people who worked in these industries during the moments I was studying. I also attended industry events to understand how digital advertising worked and followed trade publications closely to learn about new developments.

How has writing this book changed how you view or approach your research?

I have a more expansive research agenda now. Even though this book might seem to be about a niche topic, it’s really sprawling. It took me across new and old media industries, military technoscience, and mathematical optimization models. And, in the process, I was exposed to new ways of thinking critically and making sense of those things.

Any advice for aspiring book authors?

It’s important to have a solid idea of what your book is about, but it’s equally important to be open to following the trail of breadcrumbs wherever it takes you. I didn’t set out to write the book that this became. The core idea was there from the beginning, but I didn’t know what I was going to find, and I ended up learning about things I never would have expected.

Interpreting Iranian Armenian identities and experiences

photo by Megan Mendenhall

photo by Megan Mendenhall Claudia Yaghoobi is a professor in the Department of Asian and Middle Eastern Studies within the UNC College of Arts and Sciences. Her book, “Transnational Culture in the Iranian Armenian Diaspora,” released in May 2023.

Provide a short synopsis of your book.

My book centers on Iranian Armenian cultural productions produced during the past four decades in response to two pivotal historical events: the 1979 Islamic Revolution and the Iran-Iraq war of the 1980s. These events triggered a substantial migration of Armenians from Iran to the United States.

The book explores how Iranian Armenian authors and artists in the diaspora grapple with their identities as a minoritized population residing on the fringes of society. This transitional and marginal status has enabled them to cultivate resilience in the face of ambiguity. I illustrate how their adeptness at navigating ambivalence in their engagement with various cultures empowers them to transcend national boundaries, embracing a transnational perspective.

What inspired you to write this book?

As a scholar specializing in cultural, literary, gender, and sexuality studies, my research revolves around Middle Eastern literature, with an emphasis on Persian and Armenian literary traditions. My investigations have centered on individuals from marginalized groups — those who do not receive the attention they deserve in academia — encompassing aspects such as gender, sexuality, class, ethnicity, and religion.

The inception of “Transnational Culture” can be traced back to 2012, when I began working on Zoya Pirzad’s stories and novels, leading to the publication of two articles on her works. It was not until 2018, when I was invited to present on the contributions of Iranian Armenians to the Iran-Iraq war efforts at the Association of Iranian Studies conference, that I became acutely aware of the lack of recognition for the substantial cultural influence of the Iranian Armenian community on Iran. This revelation served as the catalyst for writing this book, a project that acknowledges both my Iranian and Armenian heritages.

What kind of research went into this project?

As an interdisciplinary scholar, my research draws upon various sources, including fiction, film, visual arts, ethnographic materials, historical documents, and feminist and literary theories. My primary research methodology involves examining original texts through close reading and textual analysis via extensive library-based and archival work.

How has writing this book changed how you view or approach your research?

My first two books centered on academic writing. But during the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, I recognized the pressing need for scholars like myself to translate our writings into a language that could resonate with a wider audience. I made a deliberate choice to include personal life vignettes and language that is accessible and engaging for a broader readership.

Any advice for aspiring book authors?

It gets much easier after the first book.

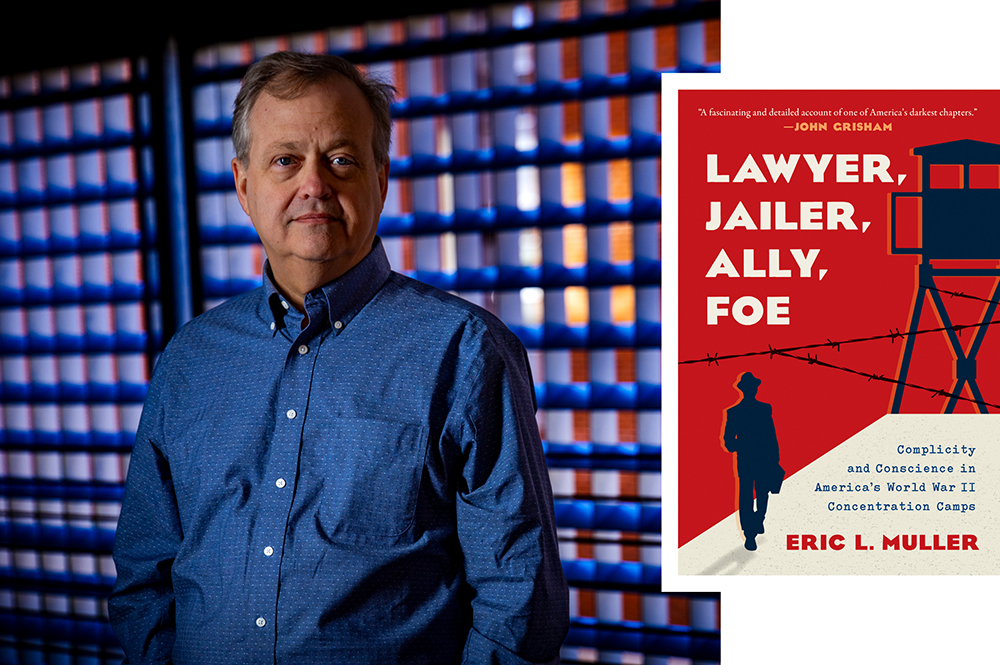

Illuminating the complicated past of WWII lawyers

photo by Megan Mendenhall

photo by Megan Mendenhall Eric Muller is the Dan K. Moore Distinguished Professor of Law in Jurisprudence and Ethics within the UNC School of Law. His book, “Lawyer, Jailer, Ally, Foe: Complicity and Conscience in America’s World War II Concentration Camps,” released in May 2023.

Provide a short synopsis of your book.

Prisoners in the World War II concentration camps for Japanese Americans could, on any given day, be both clients and victims of the government lawyers who helped run the camps. These lawyers had impossibly contradictory responsibilities: They helped oversee the day-to-day administration of the camps, they settled internal disputes between prisoners, they managed conflict between prisoners and their government captors, and they advocated for prisoners in their dealings with the hostile communities surrounding the camps and back on the West Coast.

In recreating the daily lives of these War Relocation Authority attorneys, the book captures its historical subjects as three-dimensional, flawed human beings. It adds color, nuance, and pathos to the historical record by creating narrative and dialogue, illustrating how the lawyers’ backgrounds, temperaments, circumstances, and personalities shaped their engagements with the unjust system they helped operate. It powerfully illuminates a shameful episode of American history through imaginative narrative grounded in archival evidence.

What inspired you to write this book?

As the son and son-in-law of Jewish refugees from Nazi Germany, I’ve spent most of my life trying to understand how ordinary people came to support and implement the persecution, and ultimately the murder, of the Jews of Europe, including some of my own relatives.

Having written several books focusing on the experiences of the Japanese Americans who were unjustly uprooted from their homes and imprisoned in the United States, it was natural for me to turn my attention from the jailed to the jailers. The evidence these government lawyers left behind makes unquestionably clear that they disapproved of the system they helped to operate. They seemed a perfect test case for exploring questions of complicity in the American, rather than European, context.

What kind of research went into this project?

The core of the research was an enormous cache of highly detailed and personal letters the government lawyers were required to write weekly about what they were doing and seeing in the camps. Thousands of pages of their correspondence rest in the National Archives, so my central task was to read and digest this correspondence and thereby get to know what made the different lawyers tick.

How has writing this book changed how you view or approach your research?

I’ve always wanted my writing to inform readers about the nitty-gritty of this system of mass racial injustice, as well as to touch their hearts. This book is the culmination of years in which the balance of focus in my work has slowly shifted from the former toward the latter.

Any advice for aspiring book authors?

I think everybody has some theme or story that only they can tell. And I think every aspiring writer should be looking within to find that story, to find that mood or emotion or message, whatever it is. And then over time, everything you write should be guided by that.

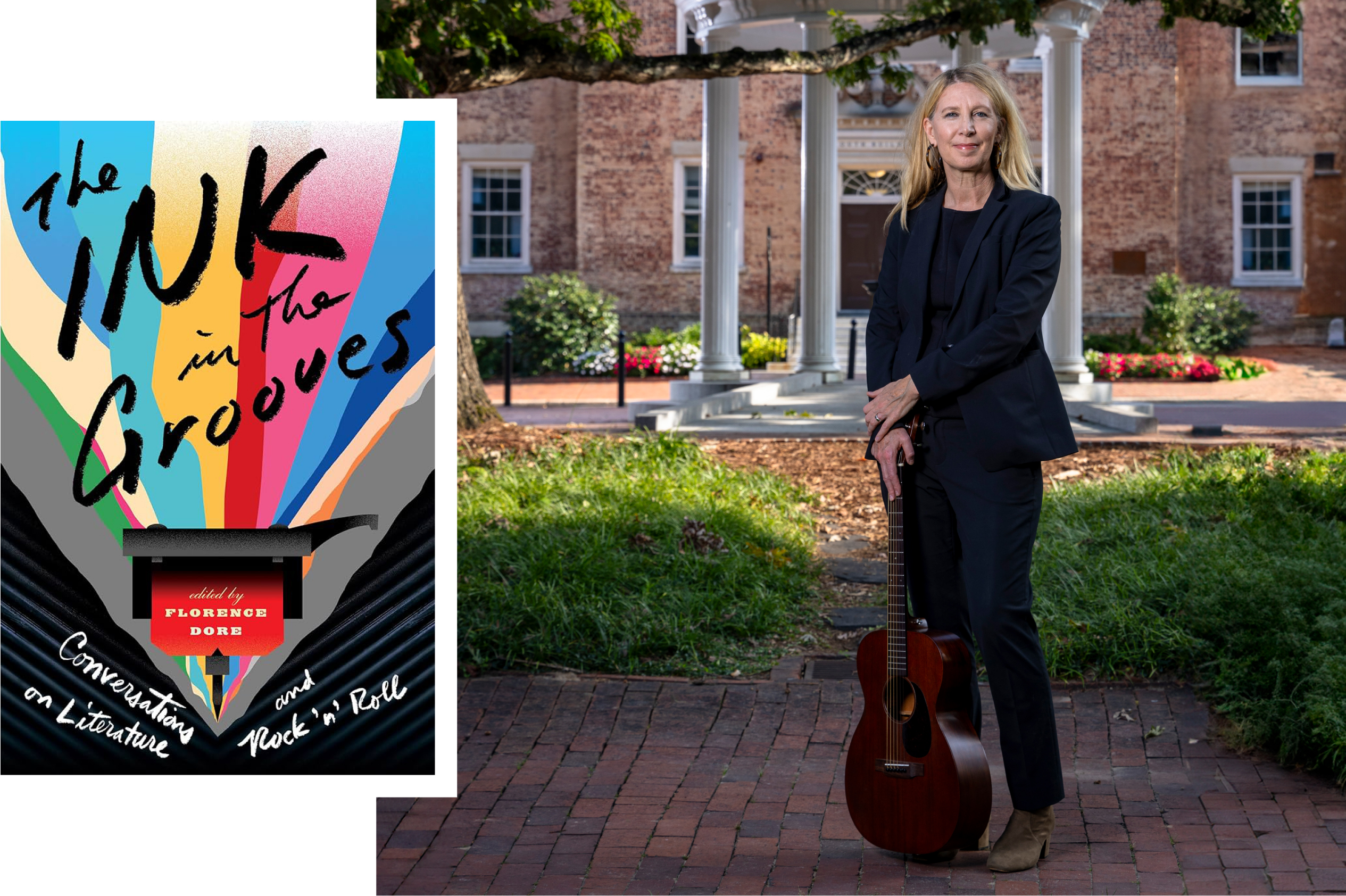

Strumming up conversations around literature and rock

photo by Megan Mendenhall

photo by Megan Mendenhall Florence Dore is a professor in the Department of English and Comparative Literature within the UNC College of Arts and Sciences. Her book, “Ink in the Groves: Conversations on Literature and Rock ‘n’ Roll,” released in October 2022.

Provide a short synopsis of your book.

“Ink in the Grooves” is a collection of interviews, essays, and fiction by renown novelists, musicians, and music writers that I curated to show the vibrant relationship between literature and rock ‘n’ roll music in our culture. Since Dylan went electric, listening to rock ‘n’ roll has often been a surprisingly literary experience, and contemporary literature is curiously attuned to the history and beat of popular music.

My book explores the provocatively creative relationship between musical and literary inspiration: the vitality that writers draw from a three-minute blast of guitars and the poetic insights that musicians find in literary works from Shakespeare to Southern Gothic.

What inspired you to write this book?

I was inspired by research for my last book, “Novel Sounds: Fiction in the Age of Rock and Roll,” and by conversations with musicians I have had in my work as a singer and songwriter. I have become increasingly interested in breaking down barriers between academia and the world beyond the so-called “ivory tower,” and “Ink in the Grooves” accomplishes that by translating my research into a more accessible form.

Another way to break down this barrier is to bring my research into community-based projects. During the pandemic, for example, I worked with students and members of the local community on Cover Charge: NC Artists Go Under Cover to Benefit Cat’s Cradle, a benefit compilation record that raised funds for the iconic Chapel Hill rock venue, Cat’s Cradle. The record came in number-one on Billboard magazine’s compilation charts.

I have also organized several public conferences on rock and literature: in 2016 and 2017 at the National Humanities Center with Carolina Performing Arts, and in 2010 at the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland. Over the last academic year, with generous support from various units at UNC-Chapel Hill, I also launched “Ink in the Grooves Live,” a traveling public humanities program that found me traversing the U.S. and Ireland, performing in classrooms and teaching in rock venues.

“Ink in the Grooves” is just one expression of my belief that knowledge should be available to everyone in a democratic society.

What kind of research went into creating the book?

I was interested in claims about American rock music as a disruptive force within literary studies and began thinking about how we might understand rock’s concurrence with the institutional establishment of southern literature as a viable field of study within the academy.

In 2010 I wrote what I thought would be an isolated “one-off” article on the contemporary “rock novel” — only subsequently to make the startling discovery that Huddy Leadbetter, also known as Lead Belly, appeared as a musical guest on a panel called “Popular Literature” at the 1934 Modern Language Association.

From this kernel emerged my research into the long history of anthologizing oral ballads from medieval times to the present day. Noting the crucial inclusion of key ballads — the 20th-century American, “Frankie,” and an 18th-century Scottish sea shanty, “Sir Patrick Spens” — in both literature and rock ‘n’ roll during the postwar years, I argue more broadly that the division between “high” and “low” art forms has always been spurious.

How has writing this book changed how you view or approach your research?

My investigations into the history of the ballad form have led to broader theoretical investigations into the ways oral forms fit into the claim that the novel genre is responsible for the democratic idea of the individual.

Any advice for aspiring book authors?

The author Percival Everett recently tweeted the best advice he ever got: “Write what you love, because the chances you’ll make any money writing a book are slim.” Great advice.