Old-fashioned chicken pie. Fresh corn casserole. Banana pudding. For more than four decades, Mama Dip’s has served soul food to generations of North Carolinians and has long been a destination for lovers of authentic Southern cooking. The Rosemary Street restaurant became so popular that, in 1999, its owner Mildred “Mama Dip” Council compiled 250 of her recipes into a cookbook called “Mama Dip’s Kitchen,” published by the University of North Carolina Press.

It was no surprise when the book quickly became a hit around the Hill. But much bigger things were in store.

Council was invited to appear for a 15-minute segment on the home shopping channel QVC to pitch her book. She left the air after just 7 or 8 minutes when the entire supply of 6,000 copies had sold out. She would go on again, and again, appearing on QVC more than a dozen times.

In the end, “Mama Dipʼs Kitchen” sold around 250,000 copies. Kate Douglas Torrey, director of UNC Press at the time, credits it with giving the publishing house an education in how to conduct trade cookbook distribution and marketing on a truly nationwide scale.

Information technology manager Joseph Carroll salvages a computer from the aftermath of the Brooks Hall fire in 1990. (North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

It was a stunning rebound for the Press, which a few years earlier had suffered a grueling trial: An electrical fire burned down its home in Brooks Hall in 1990, just a decade after the buildingʼs dedication. Records and items dating back to the organizationʼs founding in 1922 went up in smoke.

Fortunately, of the works that the staff were preparing for publication at the time, only one manuscript was lost and had to be re-edited. They were able to meet all other deadlines. And materials for the annual scholarly conventions where publishers greet potential authors had been shipped out just the week before.

“We could stand in front of the displays, and it looked like nothing had happened,” Torrey, then editor-in-chief, recalls. “That was a really lucky break. We could assure authors that, yes, the Press was still in business.”

The rebuilding of Brooks Hall took three years. Torrey credits sales from the monumental “Encyclopedia of Southern Culture” edited by Charles Reagan Wilson and William Ferris and published in 1989, for helping to sustain operations through that difficult time.

During its 98-year existence, the Press has struck a balance between publishing books like these, focused on some aspect of Southern life and accessible to a broad audience, and academic works targeting a more specialized scholarly market.

Such regionalism is unusual in the world of university presses. But the Press has devoted decades to publishing works about and for Southerners — in particular, North Carolinians. In doing so, it has often served as a positive force for social change.

Pushing books

The publishing house known as the University of North Carolina Press was not the first unit on campus to bear its name. UNC librarian Louis Round Wilson had encountered an earlier incarnation — a small, student-run print shop that had been set up to serve the campus in 1894 — as a graduate student.

That press only put ink on paper; it offered no assistance to authors in preparing their manuscripts or in distributing their finished works. Getting his doctoral dissertation printed meant proofreading the final copy himself. He had to do it four times, because each time he sent it back, the student employees would botch the job.

Louis Round Wilson (North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

To address the dearth of publishing services on campus, Wilson founded the UNC Press we know today on June 12, 1922, with nine other members of the faculty and three members of the Board of Trustees. More than a printer, this would be a true university press unifying editorial, production, marketing, and other business functions under the umbrella of a single organization.

The idea was, in many ways, preposterous. The first university press in the nation had been founded at Cornell just a half-century earlier, and since then the scene had been dominated by a handful of private schools. Only three public universities in the nation had presses of their own, and none of these were in the South.

“North Carolina bought more books per capita in 1855 than in 1920,” Wilson wrote in an article for the September 13, 1922 issue of The University of North Carolina News Letter. “This statement … tells the same story which North Carolina authors hear when they seek a publisher for manuscripts which have only a local, state appeal; namely, that North Carolina is one of the poorest book markets in the 48 states.”

In 1940 — the first year that the census began asking the question — only one in four adults in the United States had completed high school. That number would have been much lower two decades earlier in the South, which has historically seen lower educational attainment rates than the rest of the nation.

If there was no demand for books in North Carolina, Wilson was determined to create some. The library and the press would be his tools.

The librarian and the lightning rod

The Pressʼs board of governors named Wilson director in 1922. For the next several years, the entire staff consisted of him and his secretary, Edna Lane. Funding was hard to come by, and things were off to a slow start.

Then in 1925, he was ordered by his doctor to take a medical leave of absence. He drafted one of the young men working at the library, William Terry Couch, to run the press while he was gone. Couch, who became assistant director upon Wilsonʼs return and director when he left the university in 1932, proved to be a natural at the job.

William Terry Couch (North Carolina Collection Photographic Archives, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

The story of how the Press was born, survived, and began to thrive can be traced back to the efforts of these two men. In many ways, they shared a vision of what a university press could be. But their personalities couldnʼt have been more different.

Wilson was a master at getting things done efficiently and with as little fuss as possible — though he could raise one when he needed to. UNC Chancellor Robert Burton House described him as “one of the most constructive persons of his generation in the entire university world.”

He was not only instrumental in founding the Press, but also founded the School of Library and Information Science, serving as its first dean; and the Carolina Alumni Review, serving as its first editor. He increased the collection of the UNC library from 32,000 volumes to 235,000 and spurred the university to build the library building that would one day bear his name.

“[The student assistants in the library] wondered what Mr. Wilson did with his time. So far as we could see he did nothing,” Couch wrote in “Twenty Years of Southern Publishing,” his essay reflecting on his days at Carolina.

That was Bill Couch — blind to subtlety and blunt as a meat-ax. Where Wilson was skilled at operating behind the scenes, Couch was more likely to tear the curtain down. During his years as director, he courted controversy in order to establish clear precedents for what the Press would be allowed to do and to shake his fellow Southerners out of what he saw as a toxic intellectual complacency.

But he was a constructive person, too. When he started as assistant, the Press was nothing but a filing cabinet in Wilsonʼs office. When he left the university 20 years later, it was a regional powerhouse, praised for its high-quality output and bold publishing choices.

As they worked together, and Couch started ruffling feathers — dressing down the university business office, defying the Pressʼs board of governors, and butting heads with Howard Odum — Wilson no doubt faced many calls to reign in his hot-headed assistant. But he kept right on doing “nothing.” He had known of Couchʼs propensity for envelope-pushing when he brought him on board.

“I was not to realize more than vaguely until many years later that, underneath his placid exterior, Mr. Wilson harbored some ideas not utterly unlike my own, that he had the ability to do quietly things which I could manage, if at all, only with noise,” Couch wrote.

A press for the Southern reader

UNC had taken an early lead in establishing a state university press, and there were very few precedents for how it ought to operate.

“The University of North Carolina Press had to determine for itself whether its sponsorship by the state involved an obligation to print books for the state,” wrote Lambert Davis, director from 1948 to 1970, in his essay “The Regional Approach.”

Wilsonʼs original intent had been to create an outlet for material by UNC researchers, whatever their subject matter and wherever their audience might be. But much of the work being done by North Carolina scholars was already regional in nature.

In particular, Howard Odumʼs presence on the Pressʼs board, and its early financial dependence on the Institute for Research in Social Science (known as The Odum Institute today), resulted in the printing of a large volume of material examining life in the South.

That relationship began in May 1924 when Beardsley Ruml, director of the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial, came to Chapel Hill to visit Odum and discuss providing funds for the institute. Odum encouraged him to drop in on his friend Louis Wilson before leaving town.

Ruml was skeptical of Wilsonʼs vision of the Press as a vehicle for the universityʼs research. Couldnʼt the institute just as easily publish its studies through one of the more established out-of-town presses?

Then Wilson mentioned a 1910 study that the Rockefellers had hoped to use as a lynchpin for one of their most famous public health reform projects. The paper, which found that 30 percent of all rural Southerners suffered from hookworm disease, had employed sound methodology. But it was almost universally rejected by state departments of public health throughout the region, which described its findings as “damned Yankee misrepresentation!”

Wilson, who knew that the planned instituteʼs studies would shine a harsh light on many of the Southʼs social and cultural shortcomings, argued that such work would be much harder to dismiss if it came with the imprint of the University of North Carolina. Ruml agreed. The Rockefeller Memorial would provide the press with $6,000 a year as part of the grant for Odumʼs institute. It was a small sum that was nonetheless crucial for sustaining early operations.

Reading between the research

In 1932, as the nation continued to descend into the Great Depression, the funding Wilson had secured from the Rockefellers ran out. That same year he left UNC to become dean of the Graduate Library School at the University of Chicago.

Couch, now director, paid a visit to university president Franklin Graham and offered to close up shop. Graham insisted that the Press continue, even if he could only offer moral support and some measure of editorial freedom. It would be two years before the university would provide any additional money, and two more years before Couch found outside funding that allowed the Press to arrest its downward spiral into debt.

In the meantime, they would rely on book sales to survive. This was a tough position to be in. A university press exists to publish worthy scholarship, especially that which could never be picked up by commercial presses because it had no chance of making a profit.

The Press decided to try something new. In the next few years, they published two textbooks about North Carolina for elementary school children: “Discovering North Carolina” by Nellie Rowe and “The Story of North Carolina” by Alex Arnett and Walter Clinton Jackson. Both books frequently referred readers to Samuel Huntington Hobbsʼ book, “North Carolina: Economic and Social,” for more in-depth information.

The result was a boost in sales for Hobbs’ scholarly work. Couch would repeat this model wherever he saw the opportunity.

There is a longstanding bias in the world of university presses against publishing applied research, or works of a more practical nature that might appeal to a popular audience. Couch did not share this bias. He hoped to emulate the Oxford University Press, which for over four centuries had been publishing high-quality trade books alongside its scholarly work. The profits that came from selling books to a general audience had allowed Oxford to absorb losses from specialized research that was important but of interest to only a few.

Throughout the 20th century, the UNC Press would have great success publishing not just scholarly books and textbooks about the South, but also cookbooks, travel guides, field guides for nature lovers, and occasional works of fiction focused on the area.

In 1997, when “Encyclopedia of Southern Culture” editor William Ferris became chair of the National Endowment of the Humanities, the Press doubled down on its commitment to regional trade publishing.

“We had the editorial muscle to do it. We had the production muscle to do it. We could figure out the complex national marketing, sales, and distribution muscle to make it successful,” says former Director Kate Douglas Torrey. “The Press considers these books an opportunity and a responsibility.”

In 2019, the Press announced a new imprint, Ferris & Ferris, under which it would print books about the South by high-profile authors. It is named for Ferris and his wife Marcie Cohen Ferris, both former UNC-Chapel Hill professors who specialize in Southern studies.

Two to three new books will be released under the imprint every year. The first was “Cool Town: How Athens, Georgia, Launched Alternative Music and Changed American Culture,” by Grace Elizabeth Hale, released in March 2020.

“Itʼs set in Athens, Georgia, but it talks about the Southʼs position and influence on the country and on the world. And thatʼs a perfect example of what we want these books to be,” says John Sherer, the Pressʼs current director.

A press for Black Americans

In 1927, when Couch was still Wilsonʼs assistant, he commissioned UNC playwright and activist Paul Green to write an introduction for “Congaree Sketches,” a collection of stories about African Americans.

Green had established a reputation as a “race radical.” In his introduction, which the bookʼs author Edward C.L. Adams would later disown, he included a powerful image of a Black laborer emerging from the ditch to stand side-by-side with his white supervisor.

“And in the light of such benefits to hand I see no sense in the talk of segregation,” Green wrote.

When the Pressʼs board of governors reviewed the book, they would not have it. Though some of them might have privately shared Greenʼs sentiments, they refused to commit to an endorsement of desegregation by the University of North Carolina. The board voted to move forward publishing the book with the offending introduction removed.

Couch, who had anticipated this resistance, told them they were too late. Copies of the book with Greenʼs introduction had already been shipped to reviewers and dealers around the country. There was no way to get them all back, and to try would have only resulted in drawing greater attention to the controversial passages. The board relented.

He would later describe the standoff as the most important single event in his two decades at the Press. “So far as I was concerned, the decision to have a press was a decision to exercise freedom of this kind; otherwise the whole affair was a fraud,” he wrote. “I was willing to take my chances on the notion that Southerners were not essentially different from people elsewhere, that they could stand as much freedom of opinion as anybody could.”

No repercussions came from this act of defiance, and he had established that the staff would enjoy a measure of freedom in publishing works that would challenge the Southʼs racial status quo. By 1950, the Press had published 100 books by and about Black Americans, including the first book of noted historian John Hope Franklin, “The Free Negro in North Carolina, 1790-1860.” But Couch was not always a progressive presence in this regard.

“I do not want to give the impression that I regarded myself as a Moses destined to lead the children of the South out of darkness into light,” he later wrote. While he was willing to publish views from across the political spectrum, his personal belief was that segregation ought to remain in place, at least until what he viewed as the more fundamental problem of poverty in the South could be ameliorated and economic parity between the races could be achieved.

This conflict came to a head with the publication of the 1944 book “What the Negro Wants.” The collection of essays was edited by Rayford W. Logan, a Black community leader and scholar who earned a doctorate from Harvard and helped organize the Pan-African Congress. It included pieces by W.E.B. Dubois, Langston Hughes, and Logan himself.

Couch had initially promised Logan full editorial control over the project. But as essays with titles like “The Negro Wants Full Equality” and “The Caucasian Problem” began to appear, he started to have doubts.

He began to waver further after corresponding with other prominent white liberals in North Carolina, including Oscar Coffin, then dean of the School of Journalism, and Nathan C. Newbold, director of North Carolinaʼs Division of Negro Education. Both men expressed shock at how far the book was willing to go and skepticism that the views were representative of the Black community.

Couch encouraged Logan to seek out essays from Black conservatives, such as Mary McLeod Bethune, a college president who had advised Franklin D. Roosevelt and cofounded the United Negro College Fund. His hope was that these more moderate voices would provide a counterbalance. He was frustrated when the conservative essayists echoed the calls for equality and refused to print the book until Logan threatened to sue.

“What the Negro Wants” was published with an introduction that Couch himself wrote. He emphasized his disagreement with its arguments but conceded that they seemed to be an accurate representation of Black views. That introduction is often remembered as a testament to the racial shortsightedness of white liberal reformers in the Jim Crow era.

But the book itself represented a milestone for Black activists. Couch left the following year to lead the University of Chicago Press, and the UNC Press would continue over the next several decades to evolve and serve as a leading light in African American studies in the South.

In 2020, as racial inequality has moved to the foreground of the national conversation, the Press is working to meet the demand for accessible scholarly works on Black issues.

“I think now more than ever thereʼs much closer alignment to the vision that we have as a publisher, to make sure these voices are being amplified, and that weʼre on the cutting edge of things,” Director John Sherer says.

A press for all people

Editor-in-chief Alice T. Paine (center, seated) is shown surrounded by members of the editorial department in this 1947 staff photo. (Louis Round Wilson Special Collections Library, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill)

The Press has also boosted other historically underrepresented voices, hiring women to fill key editorial positions from its early days. Alice T. Paine started work in 1929 and served as chief editor for several decades. Manager Porter Cowles joined around the same time and worked as the Pressʼs acting director from 1947 to 1948.

The earliest work published by the Press that focused on women was historian Julia Cherry Spruillʼs “Womenʼs Life and Work in the Southern Colonies” in 1938. In the 1960s and ’70s, womenʼs studies began to be recognized as a distinct academic discipline. The Press took an early lead in publishing works in this area, including “The Emancipation of Angelina Grimké,” by Katherine DuPre Lumpkin, and “Sylvia Plath: The Poetry of Initiation” by Jon Rosenblatt.

Momentum continued to build through the 1980s under editor-in-chief Iris Tillman Hill. During that decade, the Press launched the Gender and American Culture series, which continues to this day. Books such as “Reading the Romance” by Janice Radway and “The Land Before Her” by Annette Kolodny influenced an entire generation of scholars.

Since then, the Press has added programs in Indigenous studies, LGBT studies, Islamic studies, Latino studies, and more, reflecting academiaʼs growing interest in representing the full spectrum of voices that make up contemporary culture — and the variety of social science and humanities work being done by UNC departments and centers.

Into the future

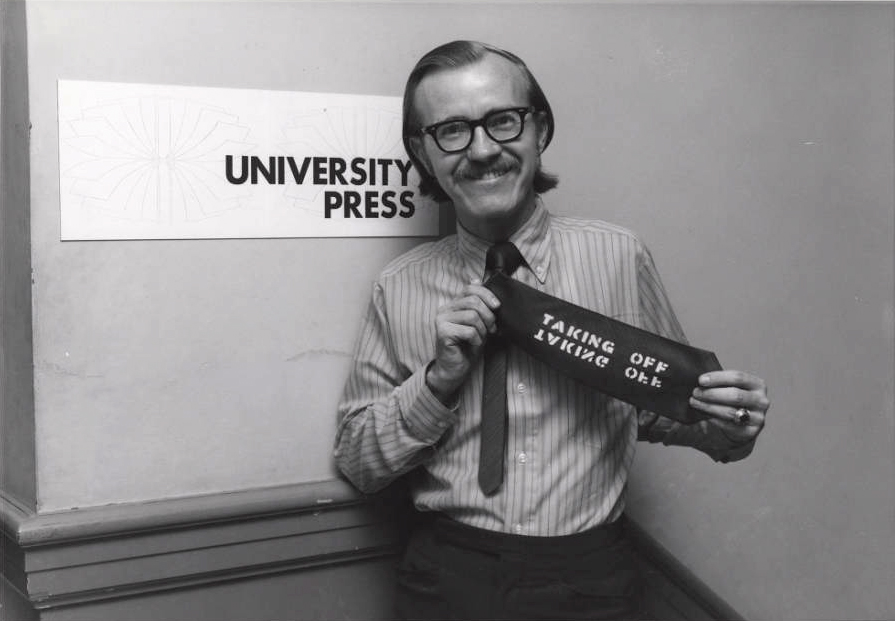

In 1970, the Press found itself in debt after a contraction in the market for academic monographs — the single-topic books by academic researchers that form the foundation of a university pressʼs publication list. That was the year Matthew Hodgson began his 22-year tenure as director. An article in The New York Times quipped that “he was greeted by the faculty his first week on the job, and by bill collectors the second.”

Hodgson worked to diversify revenue streams. He sought funds from private sources, built up the Pressʼs endowment, and incorporated technological and business reforms to improve efficiency.

“Within a short time, Chapel Hill became a center for disseminating information about technical advances in book publishing,” he wrote in his essay “New Challenges, New Opportunities.”

These were boom times. When Hodgson left the Press in 1992, it was debt-free, had an endowment of $7 million, and was selling 15 times as many books annually as it had been in 1975. And it had developed expertise about how to run a press leanly without sacrificing editorial quality — expertise which it was willing to share with others.

The digital age has created additional challenges. In the 2000s, as internet bookseller Amazon grew in size and reach, it began to impose increasingly stringent requirements on publishers. The long-established logistics of book printing, distribution, and marketing were upended.

“It was becoming increasingly clear that either UNC Press books were going to be distributed by someone else, or that we needed to take on the distribution of books for other publishers,” Torrey says. “It was no longer a situation where every publisher could afford to have its own order fulfillment department and warehouse.”

In 2005 the press entered into an agreement with UNC to turn over the land where its book warehouse was located to the university. The Press contracted with an outside vendor for storage of its books and received about $1 million from the university for the deal.

This money was used to start a new independent subsidiary, a not-for-profit affiliate organization called Longleaf Services, which would provide a suite of publishing services to other university presses. Its clients — which now number 19 — pool resources and use their collective buying power to negotiate better rates on storage, distribution, and other costs.

Despite being founded by and located at Carolina, the Press is an independent organization and an affiliate of the UNC System as a whole. In 2015, it established the Office of Scholarly Publishing Services (OSPS) to better serve the needs of academic researchers throughout the university system.

At that time, Sherer felt the press was not adequately prepared to publish in areas other than its traditional strengths.

“And that felt like a real weakness,” he said. “What we realized is we needed to be prepared for publishing that looks nontraditional for a university press.”

The OSPS has tackled a broad array of initiatives, including revivals of out-of-print books, library-based publishing programs, conference proceedings, and manuscript reproductions. It has published an e-book with the Eshelman School of Pharmacy and partnered with the School of Government on its publications program.

“I want us to get much more deeply engaged with the UNC-Chapel Hill campus,” Sherer says. “Come talk to us, challenge us. If people think publishing is broken, and they want new ways of doing it, I want them to think, Hey, weʼve got a potential partner there who can help us change the system.”