“He loved the South — lived it, breathed it, and wanted it to be all it could be. He was fascinated with human beings, and I think that’s what drew him to the social sciences.”

–Kathy Hill, granddaughter of social science innovator Howard Odum

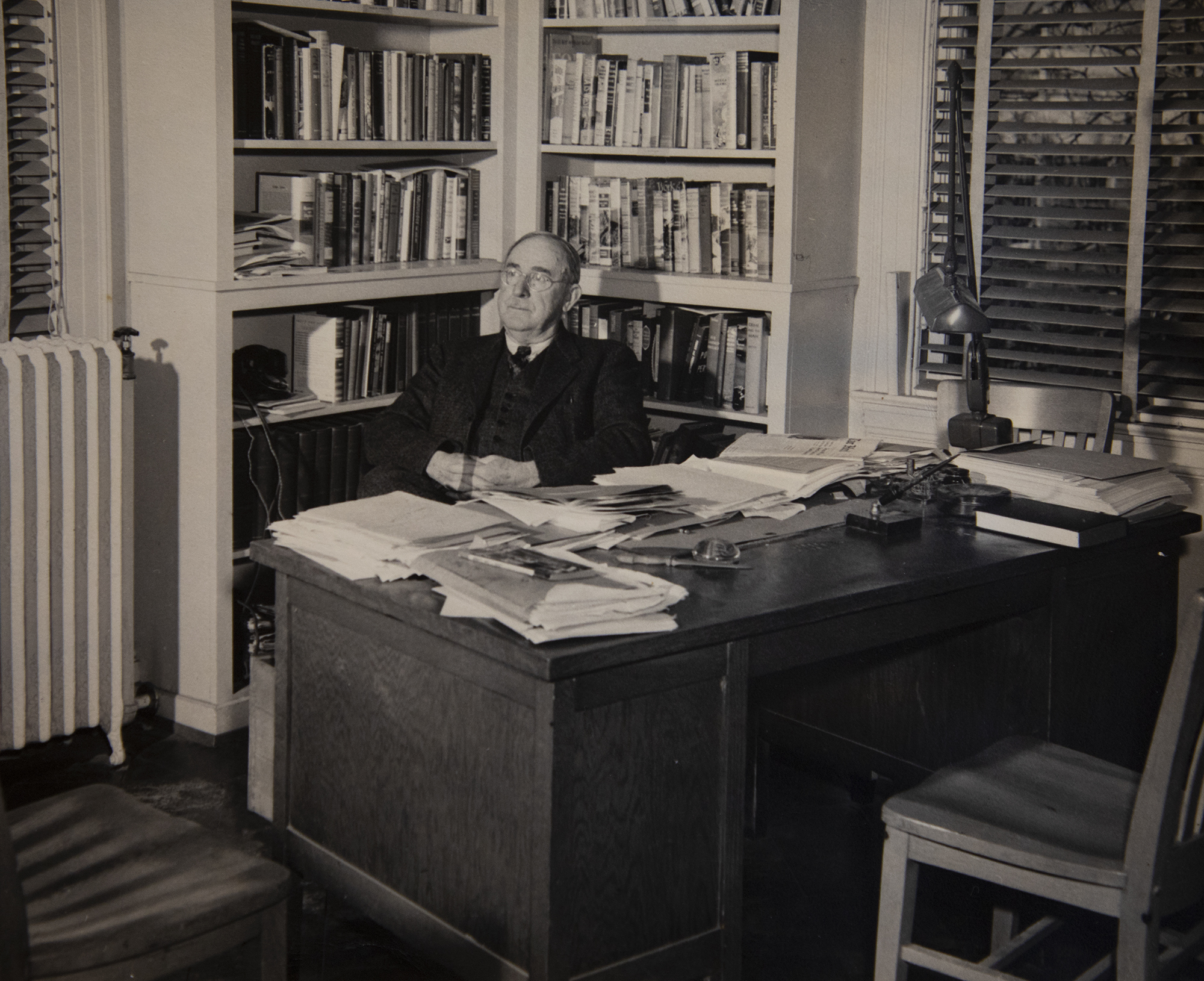

Restless, indefatigable, a spirit of challenge. These are how people describe Howard Odum. At six-foot-two, he was big in stature but more so in character. He worked 18 to 20 hours a day and at home could often be found sitting amidst piles of books and papers in his office, deep in thought or writing.

He didn’t care for small talk or parties and, in general, found social life trivial. He would kick off a meeting only to sneak out to go write in his office, returning about an hour later to wrap things up. But what he lacked in interest in routine matters he made up for in enthusiasm. He was always moving, his thoughts pouring from his lips like a late-afternoon deluge — so much so that students had trouble keeping up with his lectures. He even signed his letters, “Hurriedly yours.”

“His eyes were on fire,” Kathy Hill, his granddaughter, remembers of him. “He was this burning fuel who had his wing of the house and everyone gave him berth.”

Like moths, his flame drew the attention of his colleagues as well. “He was like a human dynamo,” Guy and Guion Johnson, the husband-and-wife team that became Odum’s first research assistants, once wrote. “Always active, constantly generating new ideas.”

Odum arrived at UNC in 1920 with “a head full of dreams.” By the time he was 36, he had already earned PhDs in psychology and sociology, and published his first book. In his first two years at UNC, he founded the School of Social Work (then called the School of Public Welfare), organized the Department of Sociology, and started the Journal of Social Forces — all the while raising pedigreed Jersey cattle.

Odum arrived at UNC in 1920 with “a head full of dreams.” By the time he was 36, he had already earned PhDs in psychology and sociology, and published his first book. In his first two years at UNC, he founded the School of Social Work (then called the School of Public Welfare), organized the Department of Sociology, and started the Journal of Social Forces — all the while raising pedigreed Jersey cattle.

Perhaps most importantly, he founded the Institute for Research in Social Science (IRSS) in 1924. Today, it’s better known as the Odum Institute for Research in Social Science, the oldest university-based interdisciplinary social science research institute in the world.

What began as home base for UNC researchers focused on the social and economic problems of the South has evolved into a center that fosters interdisciplinary research and offers training, consulting, and other support services to faculty across campus.

But how did it become this? The answer, for both Odum the man and the institute, is people.

Ahead of his time

Guy Johnson knew Odum on paper before meeting him in person, their relationship a product of handwritten letters and Johnson’s first submission to the Journal of Social Forces — a piece on the Ku Klux Klan. Johnson, a sociologist, agreed to come to UNC in 1924, but only if his wife Guion could get a position, too. At the time, she was heading the journalism department at the Baylor College of Women. Odum offered them both $1,500 and a research assistantship.

Guion was the first female research assistant ever hired at the university. Within a year of her arrival, Odum also brought in Harriet Herring, who spent the next 40 years researching the social ills connected with the industrialization of the South. He also hired Katharine Jocher, who began as the institute’s executive secretary, but was ultimately named assistant director in 1927 and stayed in that role for 30 years.

“[Odum] was a pioneer in bringing women into what was pretty much an all-male institution when he got here in the ’20s,” says John Shelton Reed, director of the institute from 1988 to 2000. “Those three women were among the first, if not the first, to be taken seriously at UNC. […] Some people were not happy about it, but Odum didn’t care. He plowed ahead on that front.”

Studies of the South

In the early days of the institute, researchers invested most of their time into the social and economic problems of the South. The studies remained broad and included surveys of race, folk culture, government, agriculture, public welfare, and industry.

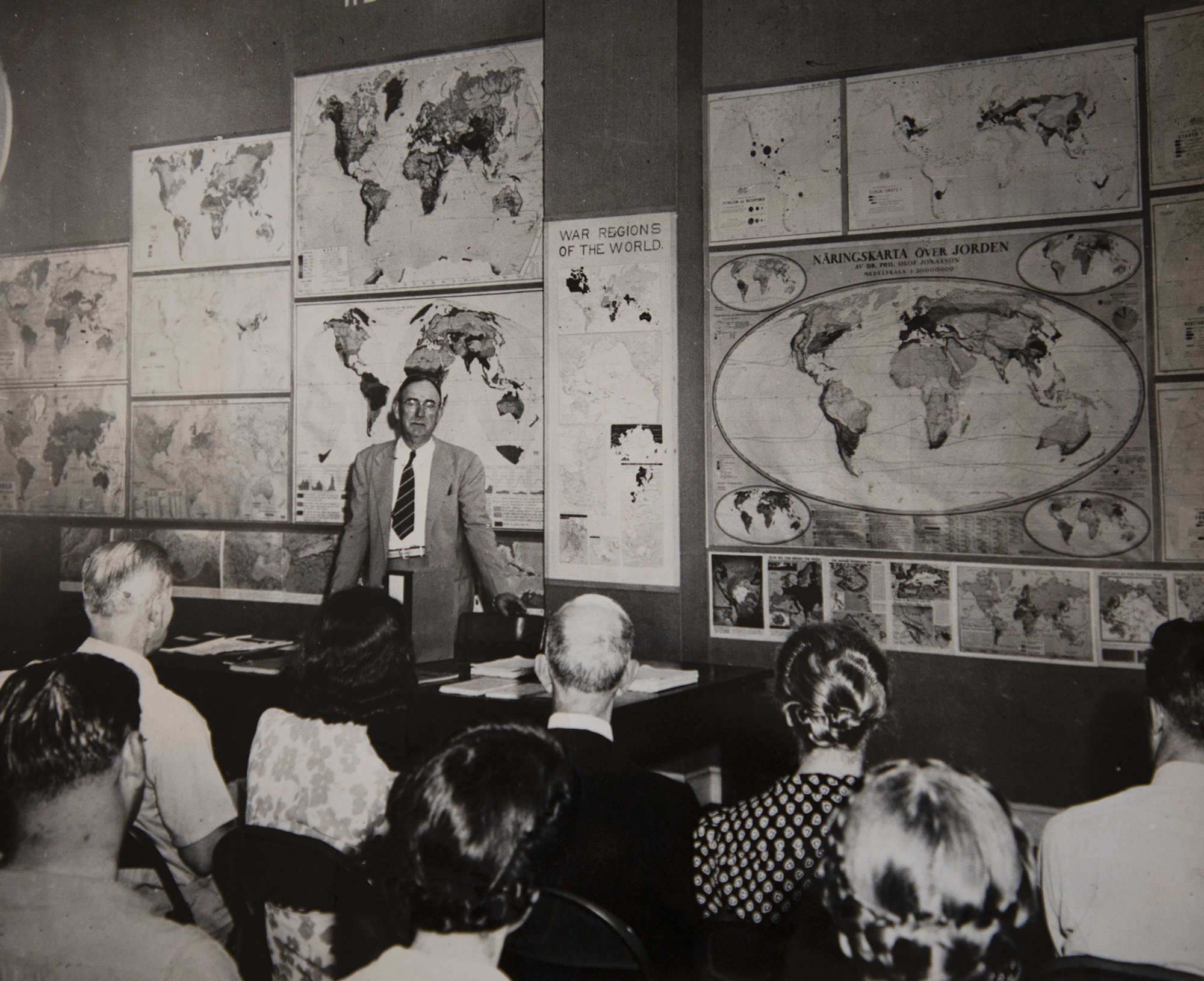

“This was a famous scene,” writes Katharine Jocher on the back of this photo. Odum leads his Regionalism Lab on the top floor of the Alumni Building in the 1930s.

“Odum had an intense devotion to the South and an abiding faith in its people,” wrote the Johnsons in “Research in Service to Society,” their book on the institute’s first 50 years. “What the South needed, he thought, was not harsh criticism but understanding, wise leadership, and self-development.” Odum wanted to show the nation why the South was different from other parts of the country, and why it was “at the bottom of the economic ladder.”

An impressive breadth of subjects permeated Odum’s own projects, from a fictional trilogy on the life of an African American man in the Jim Crow south to a two-volume national study of social trends. Race relations were particularly important to him.

“He was interested in race relations, but he was very cautious about it,” explains Reed, who points to the difficulties of being a progressive southerner during the Jim Crow era. “He knew perfectly well he could endanger everything he had built by taking too advanced a stand on race relations.” So he empowered researchers who could be more bold — people like Raper, who studied lynching and how to prevent it, and Johnson, who co-founded the Commission on Interracial Cooperation.

In 1931, Johnson invited Langston Hughes, a notable African American poet and social activist, to give a presentation at Memorial Hall. “[Johnson] wrote extensively on race relations and was constantly in and out of hot water in a way that Odum didn’t want to be,” Reed says. But Odum “understood that segregation was holding the South back,” Reed adds, and that it needed to be addressed sooner rather than later.

In 1931, Johnson invited Langston Hughes, a notable African American poet and social activist, to give a presentation at Memorial Hall. “[Johnson] wrote extensively on race relations and was constantly in and out of hot water in a way that Odum didn’t want to be,” Reed says. But Odum “understood that segregation was holding the South back,” Reed adds, and that it needed to be addressed sooner rather than later.

The institute produced numerous studies on African American life that intersected with religion, socioeconomics, and tenant farming. Odum felt that agricultural problems in particular plagued this part of the U.S. In 1926, he added graduate student Rupert Vance to his team. For his doctoral dissertation, Vance analyzed the struggles of the cotton industry — research that eventually became a book.

Raper’s research also extended into agriculture. To better understand tenant farming, he not only interviewed 300 tenant families, but moved in next door. He would dine with them, hunt and fish with them, and attend church with them. Over the next two decades, the institute would produce nine books, 25 articles and chapters, and 21 manuscripts on Southern agricultural problems.

Herring, on the other hand, investigated industrialization. Before coming to UNC in 1925, she worked as a personnel director for Pomona Mills in Greensboro, instituting the first comprehensive employee welfare system for cotton mill workers in the South. At the institute, she studied the facets of life in mill villages such as schooling, church services, recreation, public health, and housing — the information from which she compiled in a book called, “Welfare Work in Mill Villages: The Story of Extra-Mill Activities in North Carolina.”

These are just a few of the many accomplishments of the institute. By the time Odum stepped down as director in 1944, IRSS researchers had published more than 80 books and 300 articles across more than 40 fields.

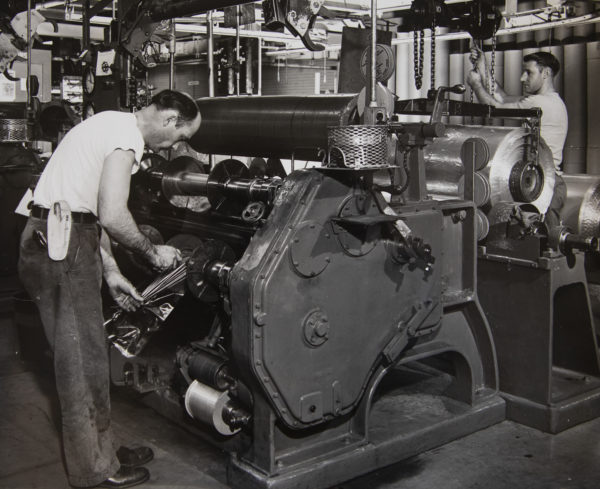

Workers in a DuPont Company plant thread a slitting machine, which cuts the wide cellophane sheet (seen on the right) into narrower strips for wrapping bread and other articles. I photo courtesy of University Archives

New roles, new goals

For the next 14 years, sociologist Gordon Blackwell would continue Odum’s legacy and help the institute grow and change with the field of social science. He proposed a program to train personnel on how to interpret research results for a general audience to help shape policy — a move that would encourage IRSS to evolve into the training resource it’s become today.

Blackwell also created a multidisciplinary team to could conduct research on human behavior. In the 1950s, he invited public health researcher Cecil Sheps and social psychologist John Thibaut to join his staff. Many psychologists who joined the UNC faculty after Thibaut, an expert in the psychology of small groups, would become affiliated with the institute.

Instead of having one specialist per research area, as was Odum’s practice, Blackwell believed in having a series of interdisciplinary projects within an overarching focal area. Those themes included political behavior, urban studies, organization, and the social science of health and health professions. By the 1960s, most of these spun off into independent programs.

The institute can be credited for creating the UNC Center for Urban and Regional Studies, while Odum, the man, helped develop the Department of City and Regional Planning. Sheps, who led multiple public health research projects at IRSS, became the founding director of the Health Services Research Center, known today as the Cecil G. Sheps Center for Health Services Research.

By the 1960s, institute goals began to shift in a new direction. Rather than be an initiator of research, it became a facilitator for projects across the university. By the following decade, then-Director James Prothro would improve the institute’s computer facilities to create a Social Science Statistical Laboratory and Data Center. In 1973, just four years after its inception, the IRSS data bank ranked among the best in American universities.

The Data Archive is now one of the largest repositories of machine-readable social science data in the U.S. Its data sets include the Carolina Poll and the Southern Focus Poll — two statewide public opinion surveys launched by the institute in the mid- to late-1980s. These studies ultimately led to the 1995 creation of the Center for the Study of the American South, a research hub focused on scholarship, conversations, and creative expressions surrounding the study of the South.

The Data Archive is now one of the largest repositories of machine-readable social science data in the U.S. Its data sets include the Carolina Poll and the Southern Focus Poll — two statewide public opinion surveys launched by the institute in the mid- to late-1980s. These studies ultimately led to the 1995 creation of the Center for the Study of the American South, a research hub focused on scholarship, conversations, and creative expressions surrounding the study of the South.

The archive is one of many resources developed by the institute in the 1990s. During that time, Director John Shelton Reed made it his mission to continue the work of his predecessors from the ’60s and ’70s and make the institute a resource for researchers from all disciplines on campus.

“We had consultants,” Reed explains. “You wanted advice on sampling or on data analysis, there were people you could talk to. You wanted a guide to census data or government documents, we had people who were familiar with them, what was out there, where to go, how to use them. You wanted help writing a grant proposal, [we] would help you out with that.”

To bolster this work, Reed and his team initiated a series of short courses on a range of topics in the social and behavioral sciences. Today, the institute offers over 100 of them, with more than 2,250 participants attending each year. “[Odum] needed to be a place where people didn’t say, ‘I don’t do that because it’s not in my job description.’ It needed to be a place that rose to whatever challenge came along,” Reed says.

Research resources

At the turn of the century, IRSS was renamed the Odum Institute for Research in Social Science and sociologist Kenneth Bollen became its new director. Bollen helped shape the framework that positioned Odum as a research support organization. He pushed for scientific rigor and focused on creating a program for survey research, improving access to spatial analysis software, and strengthening the data archive.

“[Odum has] one of the earliest social science archives at a university, where data are stored and preserved for future generations,” Bollen says. Today, the UNC Dataverse is a free resource for researchers needing to preserve, search and discover, archive, publish, or analyze data. Called data curation, this process makes data FAIR: findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable.

Taken in the 1950s, this is one of the last pictures taken of Howard Odum. He passed away in November 1954. I photo courtesy of UNC Archives

Tom Carsey, a political science professor and Bollen’s successor, spent the next seven years pushing for scientific rigor in the social sciences. He increased attendance at short courses and brought Odum’s services to the forefront. Now, each year, institute staff consult with more than 1,000 researchers who need help with independent projects and join research teams to provide critical resources like data management, cyberinfrastructure, and research reproducibility.

“Tom had a natural way of making everyone around him feel welcome and included,” wrote his colleagues in a Vox op-ed after his passing in 2018. “He began every conversation, class, seminar, or talk with the assumption that everyone in the room had the potential to contribute.” He cared about people — an attribute he shared with his long-gone predecessor, Howard Odum.

Carsey also spent a lot of time educating people about R — an obscure, high-level computer programming language for data management analysis. “It functions almost like an operating system where people have created all kinds of apps that extend its functionality to do stuff like Twitter scraping, which is crazy for statistics software,” says Todd BenDor, director of the institute today. “Tom was one of the key factors in pushing R as a framework for social science research and analysis at UNC.”

Overall, BenDor believes the institute’s most valuable asset is time. “Odum saves people time,” he says. “We give people efficient ways to push research forward, helping them with projects so they don’t have to do it by themselves. We’re focused on contributing meaningfully to research — and I think Odum would be very happy to see that something he started still has a really powerful legacy.”