When you were a child, what was your response to this question: “What do you want to be when you grow up?”

Describe your research in five words.

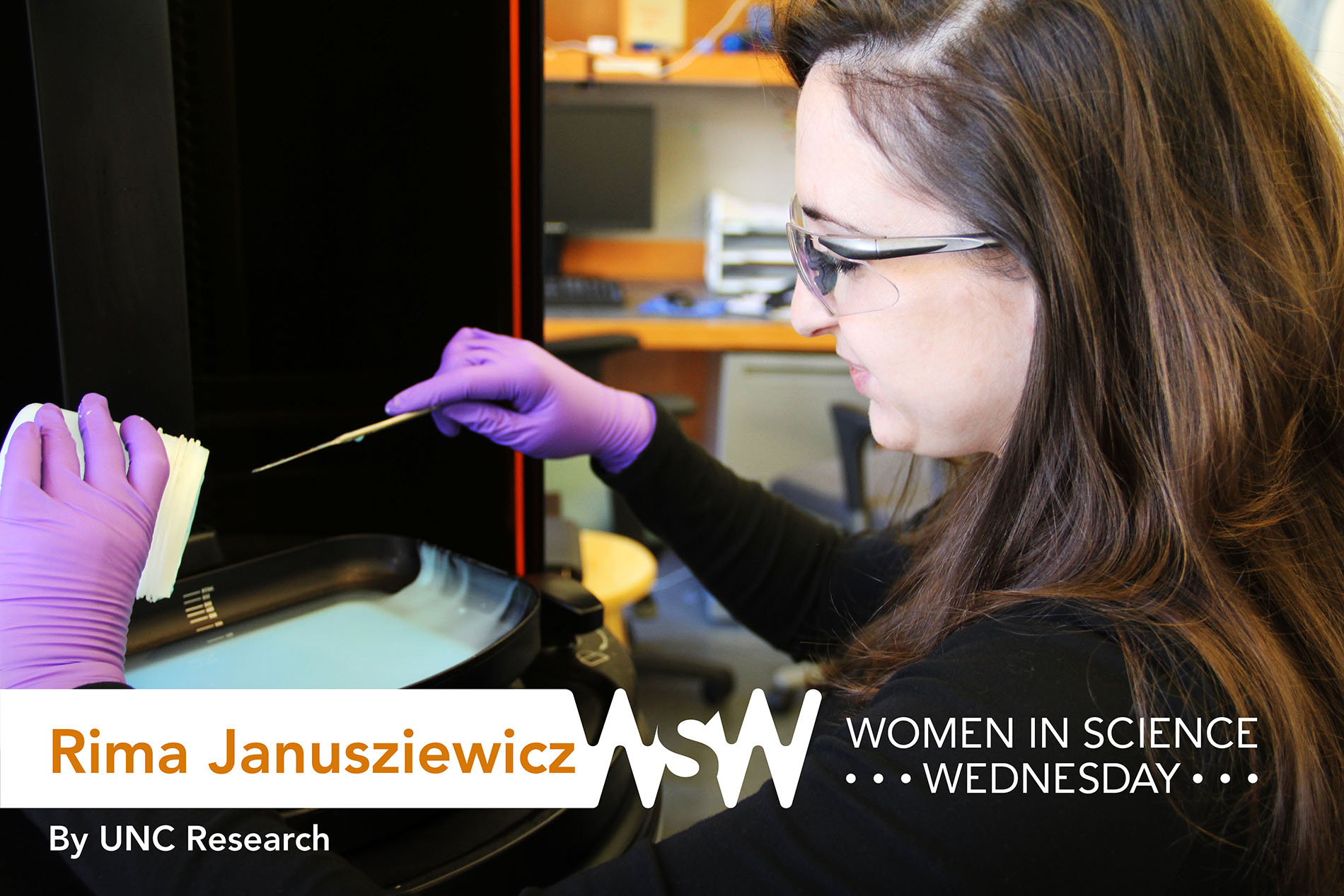

“3-D printing medical devices fast.”

Every week it was something new, from a Supreme Court justice to a comedian. If you’d asked me in high school, I think the most consistent answer would have been composer. I played viola and piano growing up — and still play to this day.

Share the pivotal moment in your life that helped you choose your field of study.

After my sophomore year, I was ready to quit chemistry. The coursework, while challenging, wasn’t impossible, but it seemed like the same thing over and over again. I just didn’t understand where this was all going — when did we get to do science? I decided to try undergraduate research as a last ditch attempt to stick with chemistry and if I didn’t like it, then I would switch to music performance and composition. When I first started, there was so much ground to cover, so much technical information to learn — then I realized I could uncover something new. That was completely different from classes. I loved it. Research is the creative outlet I was searching for. I saw my coursework in a completely new light after that summer. The classes were like learning scales, and I needed to master that before I could play music.

Janusziewicz (left) with her dad, sister, mom, and 180-pound Newfoundland, Thiggy, this past holiday season.

Tell us about a time you encountered a tricky problem. How did you handle it and what did you learn from it?

My research centers on a novel 3D-printing platform called continuous liquid interface production (CLIP), which creates continuous fabrication versus the layer-by-layer process typically used by 3-D printers. I wanted to fundamentally understand how this mechanism works and what the dynamic nature means for part resolution. I began with conventional methods, but had to get creative and go outside what was established in the field — so I settled on a laser imaging system often used in the microchip industry.

Ultimately, I was able to develop new methods to uncover the answers to my questions. This was step one of my research and really set the tone for the rest of my graduate experience. I learned that just because a method or process works in one specific situation does not mean it won’t translate to another question completely outside the field. But the transition only works if you fully understand the process, otherwise you might find yourself going down a never-ending rabbit hole.

What are your passions outside of science?

They say graduate school is a marathon and it’s all about balancing your interests and goals to keep your sanity. My sanity saver has been to learn about things and ideas completely unrelated to my research. While music is an obvious passion for me, I also really enjoy learning about history, particularly people and military strategy. I’m starting to get into calligraphy and blockchain technology. Random — but you never know when two ideas will line up!