In the 1994 NFC championship game, an incredible hit was taken by then-quarterback Troy Aikman on the third snap of the second half. After throwing the ball, 49ers defensive Dennis Brown kneed Aikman in the head, sending him to the hospital. The Cowboys still managed a 38-21 victory, guaranteeing a spot at the Super Bowl.

But Aikman can barely recall any of it thanks to the nasty concussion he received that day.

Concussions occur when the head or body receives an impact that jostles the brain inside the skull. While the most common symptoms are headaches and dizziness, people may also experience nausea, light-headedness, balance problems, light sensitivity, ringing in the ears, disorientation, blurred vision, amnesia, and loss of brain function. Multiple concussions over an athlete’s career can lead to neurodegenerative disease and depression.

For decades, doctors and coaches would respond to a hit in a game by holding up two fingers and asking, “Are you okay?” A nod of the player’s head and they returned to play.

“They would send a player back in with a suspected concussion but hold somebody out with a knee or ankle injury for two weeks,” says UNC Chancellor Kevin Guskiewicz. “There was limited science to guide clinical decision-making at that time.”

While most people know Guskiewicz as Carolina’s current leader, many may not realize he is also a renowned concussion researcher, specifically in the field of sports-related injury, and has been on the faculty since 1995.

When Aikman was hit in 1994, then NFL Commissioner Paul Tagliabue created the Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Committee. At that time, Tagliabue was quoted as saying that “steroids and drinking [are] a far greater problem” and that concussions are a “pack journalism issue.” It would be some time before concussions were taken more seriously by the NFL.

Guskiewicz, on the other hand, was already rigorously engaged in his research program at UNC, trying to uncover ways to both protect and treat athletes suffering from head injuries.

As for Aikman, he received two concussions in a three-month period toward the end of 2000 that led to his retirement in April 2001. He was only 34 years old — and had experienced a total of 10 documented concussions in his 12-year NFL career.

For those too young or unfamiliar with football to remember Aikman’s story, you’ve probably heard of Junior Seau, a former linebacker for the San Diego Chargers. In 2012, at age 43, Seau took his own life — a decision doctors believed he made because he suffered from a degenerative brain disease called chronic traumatic encephalopathy.

These are just a few of countless stories from athletes who put their brains and bodies on the line. While we still have a long way to go when it comes to preventing and treating concussions, today no one in the NFL goes back to play the same day as an injury. In 2011, a board of independent and NFL-affiliated physicians and scientists developed the NFL Game Day Concussion Diagnosis and Management Protocol, which sends concussed players through a five-phase process before returning to practice or gameplay.

Guskiewicz has not only contributed to these protocols but those of the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) and the Return to Play laws now in effect for younger athletes in all 50 states. He is the winner of a MacArthur Fellowship — often called the “genius award” — has spent decades partnering with the NFL, was one of the first researchers to put accelerometers in helmets to measure concussions in real time, and has helped change the world of contact sports as we know it today. Time magazine even recognized him for this work, calling him a “game-changer.”

But Guskiewicz would never tell you any of that.

“He is incredibly modest,” says Michael McCrea, a long-time friend and colleague from the Medical College of Wisconsin. “You could sit next to him on an airplane for three hours, and he’s probably not going to say much about his own achievements.”

He is also a visionary — a word used by multiple friends and collaborators to describe him, and a quality that set him on the path to the chancellorship.

Guskiewicz became the 12th chancellor of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill on December 19, 2019. “When you’re thinking about big and new ideas, you want him in the room,” says Johna Register-Mihalik, one of Guskiewicz’s former graduate students and current colleague in the Department of Exercise and Sport Science. “I can’t say enough about his ability to see the bigger picture and think about bold ways to address problems.” (photo by Kevin Seifert)

Steel Country to Carolina

Guskiewicz grew up in Latrobe, Pennsylvania, just 40 miles west of Pittsburgh — which hosted the first professional football game in 1895. The Steelers formed in 1933 and spent 40 years sweating yards to finally become a playoff contender in the early 1970s, a time when the team grew in popularity and a pre-teen Guskiewicz was cheering them on.

It’s no surprise that Guskiewicz began playing the game at a young age and through high school. He sustained three concussions during that time. But his love for the game persisted — so much that he earned a bachelor’s degree in athletic training and a master’s in exercise physiology. In the early 1990s, he landed a job as an assistant athletic trainer for the Steelers and spent two years working with players.

“At that time, the Steelers had arguably the best concussion program in the NFL — and yet it still wasn’t good enough. There was still too much guesswork involved,” recalls Guskiewicz, adding that ankle and knee injuries were often taken more seriously than head trauma.

That’s why Guskiewicz went on to study concussions as a PhD student at the University of Virginia (UVA). He wanted to treat and help players return to the game safely.

While there, Guskiewicz studied under neuropsychologist Jeff Barth and kinesiologist Dave Perrin. Their work helped develop a balance test specific to concussive injury called the Balance Error Scoring System (BESS). He used the system for his dissertation, testing UVA football and soccer players before their seasons began. Then, he waited.

In 18 months, 19 of those athletes received concussions. Guskiewicz put them all through the test — and many failed.

Shortly after graduating from UVA in 1995, Guskiewicz was offered a job at Carolina, where he worked with two graduate students to perfect and validate BESS. While a modified version of the system is now used by multiple universities and clinicians across the globe, research programs addressing concussions were few and far between in the 1990s.

“We’re talking about a handful of people who were doing this work,” McCrea says. “And now it’s literally hundreds, if not thousands, of people studying sport concussion worldwide.”

McCrea, a neuropsychologist, began working with Guskiewicz in 1997 after they both submitted nearly identical proposals to the NCAA for studying concussions: They both wanted to know how long it takes an athlete to recover from concussion and when it’s safe for them to return to play.

“At this point, Kevin and I had never met,” McCrea remembers. “We were both extremely early in our careers and the pitch from the NCAA was, We’d like you two to combine your proposals and, if you’re willing to do that, we’ll give you all the funding. We talked on the phone an hour later, and it was on. I often call it an arranged marriage — one that has worked out wonderfully for 25 years.”

A game-changer

In 1998, Guskiewicz and McCrea hosted a one-hour symposium on sport concussion at the American Academy of Neurology’s annual conference to share some early results: that concussion symptoms resolved, on average, about seven days after the initial injury. While thousands of neurologists attended the conference, only six people showed up to their event.

They left motivated, the need for their research more evident than ever.

In 2001, Guskiewicz founded the Center for the Study of Retired Athletes at Carolina, where he and McCrea enrolled more than 900 athletes from 25 NCAA member institutions to investigate the early, acute effects of concussion — making it the largest study of its kind in the nation at that time. They collected each player’s health history and, immediately after injury, assessed their symptoms, cognitive functioning, and balance.

From this project, they produced two landmark studies that were published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) in 2003. One found that three or more concussions sustained in a player’s career was associated with an increased risk of mild cognitive impairment, and the other made an association between three or more concussions and an increased risk of depression.

“It really brought a lot of awareness to sport concussion,” says McCrea. “Fast-forward to today, and we’re conducting large-scale studies where we’re collecting brain MRI on these participants, and we’re analyzing proteins in the blood, and we’re analyzing the effect of genetics on risk of injury and trajectory of recovery.”

Two decades later, hundreds of people now attend multiple-day conferences entirely dedicated to the field. The Center for the Study of Retired Athletes has brought over 600 former players to campus to participate in research studies and enrolled another 400 into the Brain and Body Program, which provides in-depth evaluations of a player’s overall health.

Former athletes often come into the center expecting that Guskiewicz and his team will be researching their brain, but they end up focusing on other problems. Sometimes it’s recommending surgery for a knee, hip, or shoulder — a solution that can help them start exercising again and become independent of some of the medications that might be affecting other parts of their life.

“When we see them a year later, they’re a different person,” Guskiewicz says. “I always tell my students that you can’t go in with blinders on. You have to go in holistically, thinking about all the potential issues the individual may be dealing with that might be contributing to his depression or memory impairment.”

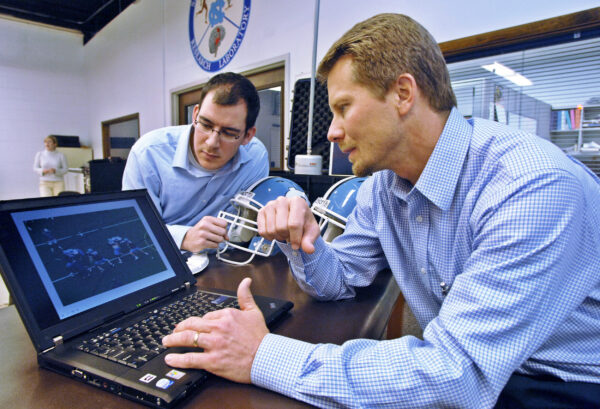

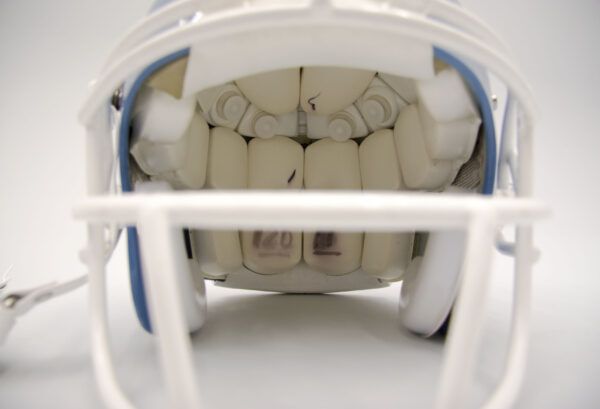

Guskiewicz and his research team wedged white accelerometers between the cushions in football helmets of UNC players to measure concussion impacts as they sustained them. (photo by Jason Smith)

Rehab and return to play

In 2004, Guskiewicz and PhD student Jason Mihalik began the first research project in the nation to use state-of-the-art technology to study head trauma during live practices and games. By placing accelerometers in between the cushions of football helmets, he monitored the head accelerations, or g-forces, experienced by 60 Carolina football players during play. At the time, researchers hired by the NFL had estimated that any hit above 85g would lead to concussion.

After analyzing 13 concussions over five seasons, Guskiewicz and Mihalik discovered that seven came from hits ranging from 100g to 169g. But the other six occurred below 85g — and sometimes as low as 60g. A player who receives one of these blows may appear only slightly dazed, so minimally that a coach or athletic trainer doesn’t notice, and the player never gets a break from play.

This is when Guskiewicz realized that concussions aren’t just about force but where and how a player is hit. During this five-year project, researchers recorded more than 104,000 helmet impacts. Multiple hits above 98g didn’t cause concussion. But one of the study participants with the worst symptoms was a Carolina running back who was concussed at 60g. Guskiewicz guessed that the brunt of the impact must have occurred on the top of his helmet. Upon further research, he found that’s where one-fifth of the impacts recorded took place.

Guskiewicz’s research projects and his involvement on the NFL’s head, neck, and spine committee led to a variety of safety measures to reduce concussions during gameplay. One was a 2011 NFL rule-change to move kickoffs from the 30- to 35-yard line to reduce the number of kickoff returns — when one team kicks the ball to the opposition, which catches it and carries it up the field. These are considered one of the most dangerous plays of the game, leading to a series of head-on collisions. The change decreased concussions by 50 percent. The NCAA also made and has seen similar changes.

Research like Guskiewicz’s has also improved the identification, diagnosis, and treatment of concussions. Between 2013 and 2018, the number of reported concussions increased by 40 percent. Most recently, Guskiewicz and his team have been focused on better rehabilitation techniques.

“We call this active rehab,” he says. “It allows us to intervene fairly early in the athlete’s recovery period to make them more resilient or better prepared to re-enter their sport or activity in a timely manner.”

The protocol used to be “rest is best,” says Guskiewicz, adding that they’d advise a concussed player to rest for a week or so in order to recover. But that’s not considered the right course of action anymore.

“To get the athlete moving sooner — if it’s safe to do so and not exacerbating their symptoms — actually helps them and gets the blood moving. It also helps them emotionally to think about how they can prepare to return to play.”

A team sport

Jason Mihalik came to UNC in 2004 to interview with Guskiewicz for the Human Movement Science PhD program. That same day, Guskiewicz was hosting a research team meeting for a CDC-funded project that was going to make Carolina one of two institutions in the world to study head-impact biomechanics in athletes.

“And here I was, this person who was interviewing to be a PhD student, who’s not even in the program, hasn’t been offered a position. And I was sitting in this meeting and staring at a 100-page grant and participating in a conversation on what the project might look like,” Mihalik says with a laugh.

Guskiewicz ultimately invited Mihalik into the program, tasking him to execute that project.

“He bestowed upon me a tremendous amount of trust and faith to pull that off, and it was quite a motivating factor for me,” Mihalik says.

The same year Mihalik visited Chapel Hill, Johna Register emailed Guskiewicz to ask if she could spend three weeks with him to complete an internship as part of her undergraduate program at the University of Alabama. An athletic training major, Register was interested in learning more on how to prevent and manage sports-related injury. Guskiewicz replied immediately, inviting her to campus.

“It was that experience and seeing the ways that research impacts clinical practice that really sparked a strong desire in me to move down that pathway for myself,” she says.

Register pursued both her master’s and PhD degrees at Carolina under Guskiewicz’s guidance. Mihalik’s focus on the mechanical aspects of head trauma, concussion assessment and management, and rehabilitation technologies paired well with her research on the negative consequences, prevention, education, and clinical management of sport- and recreation-related traumatic brain injury. Now married, the couple teamed up with Guskiewicz in 2010 to start the Matthew Gfeller Sport-Related Traumatic Brain Injury Research Center.

“It was the three of us,” Mihalik shares. “Johna wasn’t even on faculty yet, and I had just joined. And now we’re probably close to 25 people as far as faculty that are affiliated with the center, staff that we’ve hired, and students we’re training. To see that growth in 10 years is amazing.”

Today, Mihalik is the co-director of the center and Register — now Register-Mihalik — is an associate professor in the Department of Exercise and Sport Science and co-director of the STAR Heel Performance Laboratory. They are just two of 24 PhD and postdoctoral researchers, and hundreds of undergraduate and graduate students, mentored by Guskiewicz in the last few decades.

Guskiewicz attributes not only the success of the Matthew Gfeller Center and the Center for the Study of Retired Athletes but his entire research career to the supportive and collaborative environment that thrives at Carolina.

“It takes teamwork,” he says. “We often talk at Carolina about convergent science and that means not working in silos. The research team that I started back here in 1995 has grown in tremendous ways. That involves collaboration across different UNC departments and schools. Those collaborations expand well beyond the borders of Chapel Hill — and I’m proud of that.”

Teamwork is the reason Guskiewicz’s research program lives on. Even as chancellor, he continues to go into the Matthew Gfeller Center once each week and is one of the leading researchers for the NFL LONG Study, focused on improving the long-term neurological health of former and current NFL players.

“While I may be a chancellor, I’m carrying out that work as a researcher and always remaining curious,” he says. “I continue to ask this question: Why? I think that’s the most important word we should all be using on a daily basis, and if we use that we’ll always remain curious and identify the best ways to answer that curiosity.”