In a crowded emergency room of the OB-GYN department at Johns Hopkins Hospital, medical resident Mary Kimmel sits down next to a pregnant woman who looks distressed. Kimmel asks her a set of questions to determine if she could be in labor and needs to be admitted for treatment. It’s an encounter that feels almost routine at this point — it was the third time during this patient’s pregnancy that they’d had this exchange.

“She got so comfortable talking to me that she opened up about her alcohol use and how she was trying to stop drinking,” says Kimmel, a psychiatry professor and researcher within the UNC Center for Women’s Mood Disorders. “After talking to her more and more, I realized that her mental health was contributing to her alcohol use and episodes of distress.”

Kimmel encouraged the patient to enroll in a comprehensive substance-use treatment program designed for moms and mothers-to-be. Several months later, she learned the patient had taken her advice and was doing well.

This encounter helped shape Kimmel’s understanding of just how interconnected mental health is to physical health and the importance of pursuing more information on that connection as it relates to the perinatal period — the time leading up to, during, and after pregnancy. But her path to get to this moment was not straightforward.

Changing course

Being a physician wasn’t Kimmel’s first career choice. She spent her first three years out of college working in strategic health care management consulting, suggesting which emerging health topics the company’s clients should be paying attention to. Even then, Kimmel homed in on how critical the perinatal period is and the lack of understanding and resources for it. She decided to do something about it.

Kimmel pursued her MD at Drexel University in Philadelphia. Going into medical school, she knew she wanted to help women, so she chose OB-GYN as her specialty. But through her years of study, psychiatry played a bigger role in how she perceived pregnancy and women’s health.

“During my psychiatry rotation, we were asked to detail the psychological aspects of medical conditions,” Kimmel says. “I chose preterm birth and preeclampsia. It really helped me understand the biological connection between the brain and the rest of the body.”

Researchers at the time were just starting to look at these connections, Kimmel says. She read papers in this emerging field about the correlation between high cortisol levels produced by stress and preterm birth and how anxiety or depression-induced inflammation in the immune system impacts pregnancy.

Wanting to further study the impact of stress, depression, and anxiety in women, Kimmel split her residency at Johns Hopkins between OB-GYN and psychiatry. During this time, she became a mother herself.

“After having a child and figuring out how to juggle so many components in my life, it gave me a clearer understanding of what patients go through,” Kimmel says. “Not only the biological and mental effects of pregnancy, but also the health system and societal effects that make it easier or harder for patients and families to find balance.”

As a new mother, Kimmel continued her training with a fellowship at the Johns Hopkins Women’s Mood Disorders Center and connected with a researcher at the UNC School of Medicine who would eventually present her with an opportunity she couldn’t refuse.

Dreaming big

During Kimmel’s fellowship, she narrowed her focus even further to perinatal mood and anxiety disorders — mental health conditions that occur around the time of pregnancy. Specifically, she was curious about the role of the pregnancy-related hormone oxytocin when it comes to postpartum depression (PPD).

That led her to UNC Chapel-Hill and Samantha Meltzer-Brody, a leading PPD researcher who created the first in-patient hospital unit in the U.S. to provide care for pregnant people, new mothers, and their babies. Kimmel had to learn more, so she visited the UNC Perinatal Psychiatry Inpatient Unit to see it for herself.

“The unit has women come from all over the country for treatment during pregnancy or postpartum because it’s so difficult to find this care,” Kimmel says. “And the associated research that’s conducted informs the care that’s provided to these women.”

Invigorated by what she saw happening at Carolina, Kimmel used the remainder of her fellowship to dive into PPD biomarkers — measurable signs of a condition or disease that appear in various bodily systems like heart rate, hormone levels, and inflammation.

It was at that point that she received an offer from Meltzer-Brody.

“Samantha called me and asked if I would be the medical director of the inpatient unit and I said, Wow, that’s my dream job, yes!”

Reading the signs

As Kimmel took on leadership of the program, she examined the care that was provided and which approaches seemed to be working. She also concentrated on patients with severe PPD, anxiety, or psychosis who weren’t responding to common treatments and turned to research to find better methods.

“If we can better identify the signals our bodies send when we are nearing or experiencing a depressive episode, we can do more to prevent and treat it,” Kimmel says. “But because of the complexity of mental health, those signals cross multiple systems and may look different for different people.”

Kimmel continued her study of biomarkers in search of identifiers that could help with diagnosis and management of certain mood disorders. She’s now looking to the autonomic nervous system — in charge of involuntary processes like breathing, blood pressure, heart rate, and digestion — as it relates to heart rate variability, or how the amount of time between heartbeats can fluctuate.

“If we gain a clear understanding of how mood disorders impact the autonomic nervous system, and how that impacts heart rate variability, we arrive at a biomarker that is easily tracked,” Kimmel says. “We can measure this in a health care setting through an electrocardiogram, and the data may eventually be available to patients by using a smart watch.”

If patients can monitor their own biomarkers, they can advocate for their own care and potentially even prevent the onset of a depressive episode by deciphering the signals their bodies are sending. With this kind of biofeedback, patients can calm their autonomic nervous system by training their thinking patterns, further enhancing the mind-body connection.

Changing the norm

While treating patients and searching for better ways to identify and treat women’s mood disorders, Kimmel had her second child.

“I still run into former patients who remember me being pregnant during their time in the perinatal unit, and they ask how my family is doing,” Kimmel says. “Seeing me as a mother in addition to a physician made an impact on them.”

It was around this time Kimmel discovered a new challenge — making the care and knowledge that her team provides accessible to all women.

Kimmel worked with the N.C. Department of Health and Human Services to obtain a grant from the Health Resources and Services Administration to expand access to this kind of care by educating frontline providers on how to screen and diagnose patients, prescribe medications, have conversations about mental health, and get their patients access to higher levels of care when necessary. The program, now five years old, is called N.C. Maternal Mental Health MATTERS.

MATTERS also runs a consultation line for providers staffed by a group of mental health specialists. Kimmel and her team routinely go out into the community to support providers and present at meetings throughout the state to provide education on perinatal mood and anxiety.

“We also try to teach people that this isn’t just a women’s issue,” Kimmel says. “We’re talking about a large number of people impacted by women’s mood disorders — family members, employers, even whole communities. When women aren’t able to show up, things start to break down.”

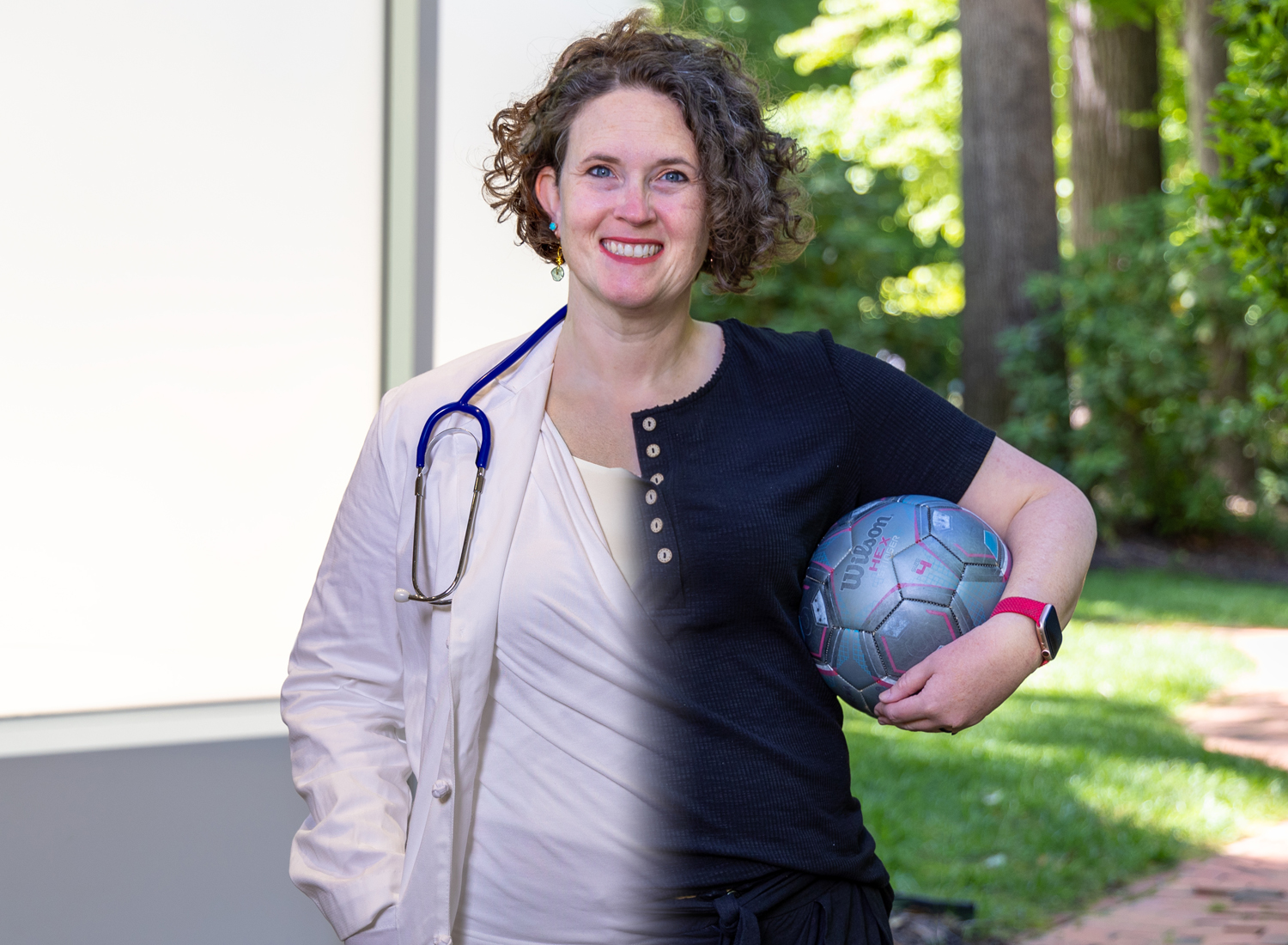

As MATTERS grew, Kimmel became director of the UNC Perinatal Psychiatry Program, which oversees the inpatient unit. She continues to balance her time as a physician, advocate, and researcher. And along with her efforts to find better biomarkers and create more accessible care, she finds time to take care of herself, so she can be there for her own family.

“A healthy mom means a healthy child, and a mom deserves to be healthy.”