When Karen Bluth taught middle school students, she saw a lot of teenage angst. She recalls one student, in particular, who exclaimed: “What’s wrong with this school? When you come here in sixth grade, you’re happy, and then when you leave in eighth grade, you’re miserable and depressed!”

Voicing a common thought children have while surviving the trials of adolescence, this student was one of many Bluth watched struggle.

“Of course, what she was experiencing was developmental changes that happen at that time,” Bluth says. “Self-compassion could have helped her deal with her depression.”

Self-compassion is treating ourselves with the same kindness as we treat others when they’re struggling. We aren’t taught how to be nice to ourselves, Bluth says. It involves three practices: Being aware of what you’re experiencing in the moment, recognizing that negative emotions are a part of the human experience, and practicing self-kindness, giving yourself the space and time to relax and recover in the face of challenges.

Bluth has practiced mindfulness since she was a teenager and believes mindful practices can ease the way to adulthood. Mindfulness is being aware of one’s thoughts and feelings — both emotional and physical — in the moment. Watching the struggles of middle schoolers inspired her to become an adolescent researcher so she could help ease the transition to adulthood.

“When I started reading about self-compassion as a grad student, it struck a chord for me,” says Bluth.

Self-compassion is being kind and forgiving to oneself in instances of suffering, failure, or perceived inadequacy. But there’s often a misconception that self-compassion means being lazy or self-indulgent, Bluth says.

“The opposite is true,” she says. “People who are more self-compassionate have more reserves, so they’re able to give more to others. They don’t burn out as much.”

People who give themselves grace when they fail are more likely to take chances and leave their comfort zone. Bluth believes fear of failure makes people reluctant to try new things, but when people stop punishing themselves for failing, that fear shrinks.

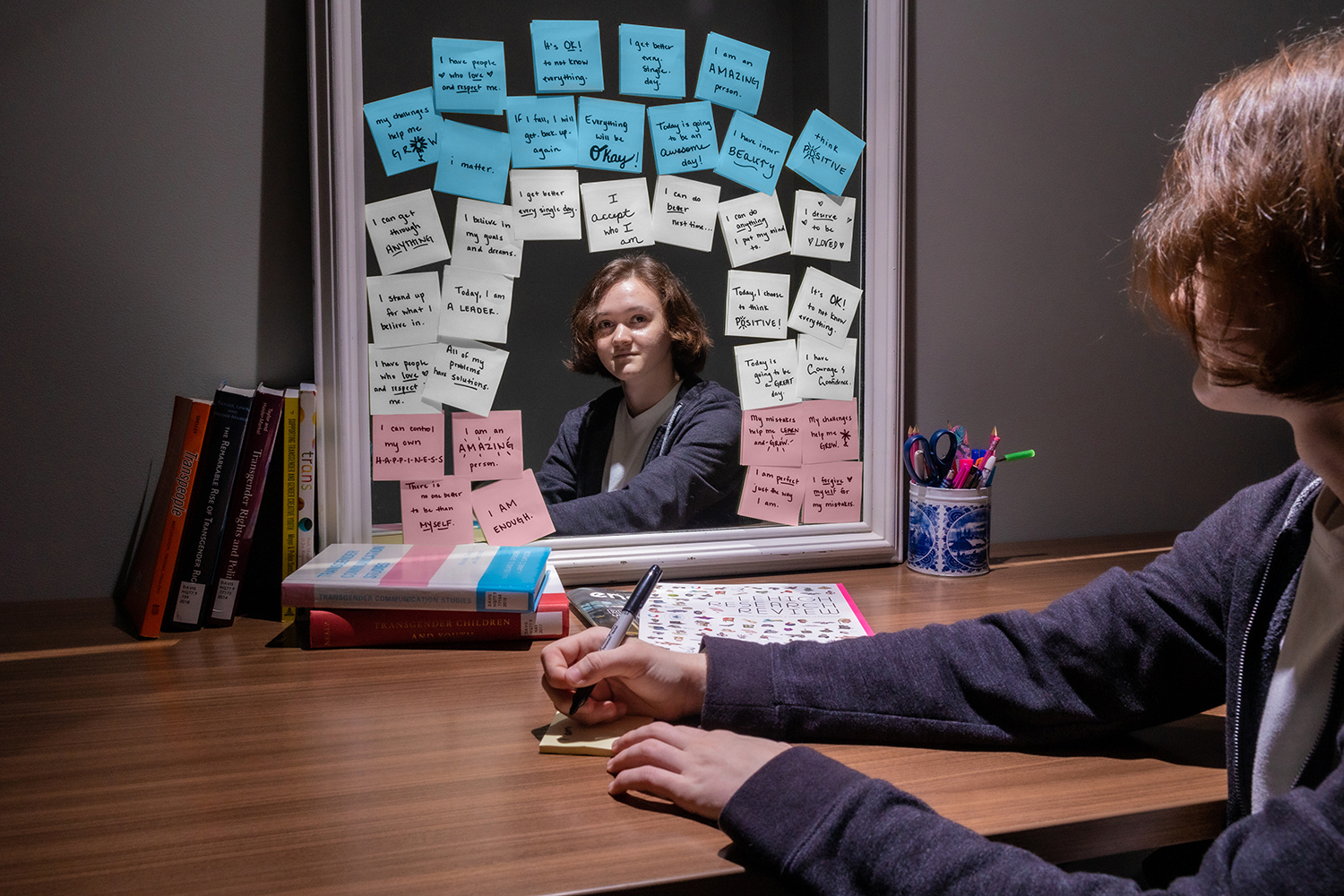

Now a professor in the psychiatry department, Bluth came to UNC-Chapel Hill in 2012 as a postdoctoral researcher. In 2014, she adapted an adult self-compassion class for teenagers, adding a segment on the adolescent brain and another on the difference between self-esteem and self-compassion. Since then, she has completed several studies to determine the effectiveness of these programs with general teen groups and specific demographics of young people like cancer survivors. Now, she’s researching how self-compassion can improve the mental health of transgender teens.

Creating a safe space

In one of Bluth’s previous teen self-compassion courses, a participant who was questioning their gender used the term “self-loathing” when referring to their own feelings. This didn’t sit well with Bluth. After looking into the data, she found statistics reporting transgender teens have higher rates of suicide attempts, anxiety, and depression than their cisgender counterparts.

“And with cisgender teens it’s pretty high, too, but for trans teens it’s just so painful to see,” Bluth says.

Without any funding, Bluth and her small team volunteered their time to assist with the program, which they offered online, partially because of the pandemic and partially because of access. They found a little money to compensate the participants.

“Some trans teens might live in remote areas, where there’s nobody they can talk to, so they’re missing the community, the sense of common humanity,” Bluth says.

Participants liked having options about speaking or showing their face to avoid feelings of dysmorphia. Cameras were kept on for safety, but they could turn off the self-view feature. Chat wasn’t allowed during sessions to reduce distractions, and there were designated socializing periods before and after the sessions where they could opt to use chat instead of speaking.

Participants liked having options about speaking or showing their face to avoid feelings of dysmorphia. Cameras were kept on for safety, but they could turn off the self-view feature. Chat wasn’t allowed during sessions to reduce distractions, and there were designated socializing periods before and after the sessions where they could opt to use chat instead of speaking.

Program facilitators helped participants realize how much nicer they are to others than they are to themselves. In one exercise, they were instructed to think of a time when a friend was struggling and what they said to that friend. Then, they were asked to imagine that they’re going through the same struggle and what they would say to themselves.

“Then we just teach them how to get out of the habit of beating themselves up and into the habit of being kind to themselves,” Bluth says.

In December, Bluth published a study that demonstrated the eight-session program retained three cohorts of participants. In a three-month follow-up survey, the teens reported that they were still practicing self-compassion and mindfulness, were less depressed and anxious, and had fewer suicidal thoughts.

“Trans people aren’t often told to be kind to our bodies. A lot of medical transition is focused on what we want to change about ourselves, or what we dislike about our bodies,” one teen said. “Being told to be kind to my body, to touch it in a way that was not malicious or self-deprecating was really meaningful to me.”

Building a community

While Bluth is pleased with the study’s results, she and her team lacked a personal understanding of the trans teen experience. Originally, she wanted a transgender person to teach the program, but teacher training for self-compassion programs is expensive and thorough. Finding a trained trans person was impossible. In the first study, she and her co-facilitators, one of whom is a parent of a trans teen, acknowledged their differences from the participating teens.

“Just naming the fact that we’re cis women, and we don’t know what it’s like to be trans, and we don’t know their experience was really important,” Bluth says. “We found that the teens responded really well to that because it’s true, for one. And if you don’t name it, they’re going to assume you think you know what it’s like. Several of them said it was empowering to them. They got to be teachers, and they got to tell us what it was like.”

“Just naming the fact that we’re cis women, and we don’t know what it’s like to be trans, and we don’t know their experience was really important,” Bluth says. “We found that the teens responded really well to that because it’s true, for one. And if you don’t name it, they’re going to assume you think you know what it’s like. Several of them said it was empowering to them. They got to be teachers, and they got to tell us what it was like.”

Now, with a grant from the American Foundation for Suicide Prevention, Bluth is working on a second study that includes an advisory board of transgender teens and adults, the parents of transgender teens, and leaders in the transgender community. This group will help guide researchers as they navigate body and voice dysmorphia and try to avoid common triggers among the trans population.

The upcoming study will also consider how a similar program that includes a workshop for parents impacts mental health, like anxiety.

“We know from research that when parents are supportive with teens, when trans teens know that they have family support, they do much better,” Bluth says.

These studies serve Bluth’s ultimate goal to teach all teens how to be kind to themselves, even if they resent their physical body or are struggling in some aspect of life.

“It’s a privilege to be able to make a difference and change lives,” Bluth says.