Research gives UNC-Chapel Hill undergrads access to unexpected places: the stage of Moeser Auditorium, the shores of Jordan Lake, and a lab bench in Marsico Hall.

This May, thousands of Carolina undergraduates will get their degrees. Their participation in research has shaped their college careers and prepared them to help solve some of the world’s most significant challenges.

“Research is so valuable,” explains Malak Dridi, a senior who has participated in several social science research projects while at Carolina. “Even if you don’t want to go to grad school or get a PhD, it teaches you writing skills, communication skills, and how to empathize with certain topics and communities.”

Malak Dridi | public policy, media, and journalism

photo by Megan Mendenhall

photo by Megan Mendenhall Malak Dridi learned two invaluable things from her first research experience as a sophomore. One, she was not interested in biometric technology, and two, she loved the research process.

The Carolina journalism and public policy major was first introduced to research during an internship at the UNC Office of Ethics and Policy, where she helped research biometric technology — like facial recognition and fingerprint software — and the university’s policies surrounding it.

During her time here, she participated in projects on a range of topics — hate crimes against Muslims in the South, democratic disenchantment after the 2011 revolution in Tunisia, and the differences in outcomes between graduates of historically Black colleges and predominately white law schools.

“I think research has truly shaped my trajectory as both an academic and an individual at UNC,” Dridi explains. “I’ve realized that research has been an avenue for me to feed my curiosity. It’s asking big questions. It’s looking at communities to try to better understand what’s happening so we can create solutions that are actually impactful.”

Over the Spring 2024 semester, she worked with public policy professor Malissa Alinor on a project studying the emotional reactions to employment discrimination and discrepancies between Asian-American and African-American populations in the United States. The project aims to understand how discrimination occurs within these communities and provide interventions to help mitigate this issue.

“We’re able to see what populations in these communities are more likely to quit their jobs or which communities are more likely to speak out and try to advocate for themselves,” she says.

One unexpected challenge Dridi faced during her research was the emotional connection she had with the community she was studying.

“I myself am a Muslim, so when researching hate crimes against Muslims in the South, I’d find myself empathizing with the stories I was hearing, finding a sense of familiarity in the trauma that these victims have experienced,” she says. “It’s important to recognize that your position as part of the community you’re researching is actually a skill and an asset to the research team because you can see things that others may not be able to.”

After graduation, Dridi will work as a legal administrative assistant with the Council on American-Islamic Relations in Washington D.C. She plans to attend law school in the next few years and eventually work as a civil rights public interest lawyer.

David Go | geological sciences

photo by Megan Mendenhall

photo by Megan Mendenhall When David Go arrived at Carolina, he wasn’t particularly interested in research, but he needed a job. So, when the geology major saw a listing for a work-study position as a lab tech in a marine geology lab, he decided that it seemed interesting enough and applied.

Little did he know, this would be the start of his research journey.

Go began in the Eidam Lab assisting graduate student Ted Langhorst with building open-source turbidity sensors that measure the amount of sediment or dirt suspended in water. The measurements help researchers determine how much sediment is settling along the riverbed and being deposited into the ocean, which has implications for water quality and land use.

Typically, these types of sensors cost between $1,000 and $5,000 to produce, but the project’s goal was to figure out how to build this technology in-house and cost-effectively.

“My job was building these sensors and then iterating on the design to make them last longer and be a little a bit tougher to hold up in harsher environments,” Go explains.

The summer before his junior year, he worked in the Rodriguez Lab at the Morehead City Field Site, helping build and install these sensors for a project tracking sediment transport across salt marshes in eastern North Carolina.

In Spring 2022, Go joined the Martens Lab to continue his work on sensor systems through a unique outreach project focused on assessing the impact of future mining operations in the South Pacific. The goal was to create sensors that could be used by students on the islands where these activities occur to help them become more engaged with science.

For his honors research project, Go continued to iterate and refine this system and create a building guide so that students in these communities and beyond can access low-cost scientific technology.

“And, if by using my tech they decide that they want to be scientists, that’s great,” he adds.

This fall, Go will start a PhD program in geology at Virginia Tech, where he will use satellite data and aerial imagery to analyze the distribution and seasonality of headwater streams, which are bodies of water a few meters in width that come together to feed larger river networks.

“It actually has nothing to do with my sensors,” Go shares. “It’s going to be all on the computer, and it’s a little sad that I don’t get to do field work, but it’s still really cool research. I’m super excited.”

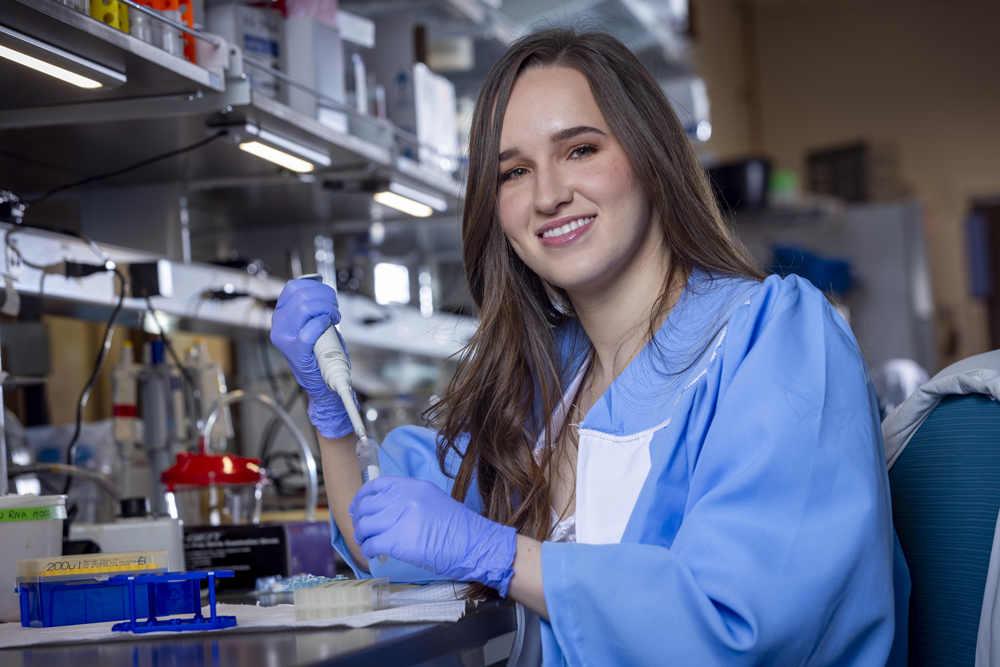

Sarah Broyhill | biology

photo by Megan Mendenhall

photo by Megan Mendenhall In 2008, Sarah Broyhill’s mom thought she was being dramatic when the then-middle-schooler repeatedly asked to stay home because of menstrual cramps.

“I was in so much pain every month,” explains Broyhill, now a senior at UNC-Chapel Hill. “The only way to get rid of the pain was to take a ton of Advil and sleep, and even then, I’d wake up and be in pain again.”

When she described her pain to doctors, she was told “it’s normal.”

When she was 20 years old, she began to feel a stabbing pain in her lower right side in addition to the ongoing cramps, which were now becoming more intense and happening in between periods.

Desperate for answers, Broyhill began to investigate her symptoms. That’s when she first learned about endometriosis, a painful condition where tissue similar to the lining of the uterus grows outside the uterus, typically in the abdomen and pelvic areas. It can cause heavy periods, chronic pelvic pain, and fertility issues.

When Broyhill asked her doctor if she might have endometriosis, her concerns were dismissed, and she was denied an ultrasound. Instead, she was offered birth control pills to manage the pain but was hesitant to take them in case they aggravated her current symptoms.

Broyhill fought for an ultrasound. When she did eventually receive one, it showed she had cyst about the size of a baseball on her ovary — and confirmed she has endometriosis. She had surgery to remove the cyst when she was 21.

“Endometriosis has a huge impact on women emotionally,” she says. “It’s one of the leading causes of infertility, but if you go to any doctor, it can take up to 10 years to get diagnosed. They don’t know where it comes from or the best way to treat it. There’s just a lot of unknowns — and it’s insane that one in 10 women suffer from it, yet so little is known about it.”

This lack of understanding about endometriosis and her desire to make an impact in health care inspired her to go back to school in 2020.

After a year at UNC-Greensboro, she transferred to Carolina in Spring 2021.

“As soon as I landed at UNC, I hit the ground running looking for a lab,” Broyhill recalls. “I quite literally Googled ‘endometriosis research UNC’ and found an NIH grant for a UNC research center for endometriosis. I saw who that grant was given to and emailed him.”

After meeting with Steven L. Young, who had recently received funding for an endometriosis research center, Broyhill joined his lab to investigate why infertility is a major complication of endometriosis.

Previous research shows that a higher expression of a protein called SIRT1 in women with endometriosis might be linked. The hypothesis is that the abnormally high levels of this protein affect the uterus’s preparation for implantation.

Because the field lacks a model organism for studying this problem, Young’s lab uses a 3D model of uterine tissue to understand SIRT1’s effects on the cell wall.

“I feel like this research makes an impact on women like me,” Broyhill says. “Down the road, if I or other women with the condition want to have kids, it will likely change our lives, which is huge.”

Broyhill plans on taking two gap years before applying to an MD-PhD program, where she’d like to get a PhD in cell biology and continue endometriosis research. Ultimately, she wants to specialize in reproductive endocrinology and infertility.

Carrina Macaluso | music

photo by Megan Mendenhall

photo by Megan Mendenhall Carrina Macaluso wasn’t looking for a research project. Instead, it found her via her Spotify playlist and lead her on a musical scavenger hunt.

While listening to music one October afternoon, the UNC-Chapel Hill vocal performance student was captivated by an unfamiliar song.

“The singer’s voice was unlike any that I had heard before,” Macaluso says.

The mesmerizing voice belonged to Connie Converse, a little-known American composer, songwriter, musician, and writer who was active during the 1950s and then mysteriously disappeared in 1974.

Intrigued, Macaluso delved into Converse’s discography and discovered that, in addition to writing songs for voice and guitar, Converse was also a composer of classical art songs. She had even created a song cycle for voice and piano called “The Cassandra Cycle,” which tells the story of Cassandra from Greek mythology.

After hearing the cycle, Macaluso was eager to perform it, but she needed to find the sheet music first. Through her research, she learned of Howard Fishman, an author writing a biography on Converse. On a whim, she emailed him to ask if he knew where to find the score.

To her amazement, he responded with copies of Converse’s original, handwritten manuscripts. He also connected her with a producer in New York who was actively working on commissioning a digitized version of the songs.

Macaluso then enlisted the help of music professor Naomi André to work on the research project with her. André agreed, and Macaluso spent her winter break reading Fishman’s biography and learning Converse’s music in preparation for her performance.

“It was fun getting to work from the ground up and building my own interpretation from Converse’s manuscripts,” Macaluso says. “The handwritten manuscripts were helpful. You can see all of the little notes that Converse makes for how to perform the song, including tempo markings for how fast or slow you should sing.”

In March, Macaluso gave an hour-long lecture and recital on Converse’s work and performed “The Cassandra Cycle.”

“This cycle has really just struck a chord with me, and I would love to record these songs at some point in my career,” she says.

This fall, Macaluso will attend the University of Colorado Boulder to pursue a master’s degree in vocal performance and pedagogy.

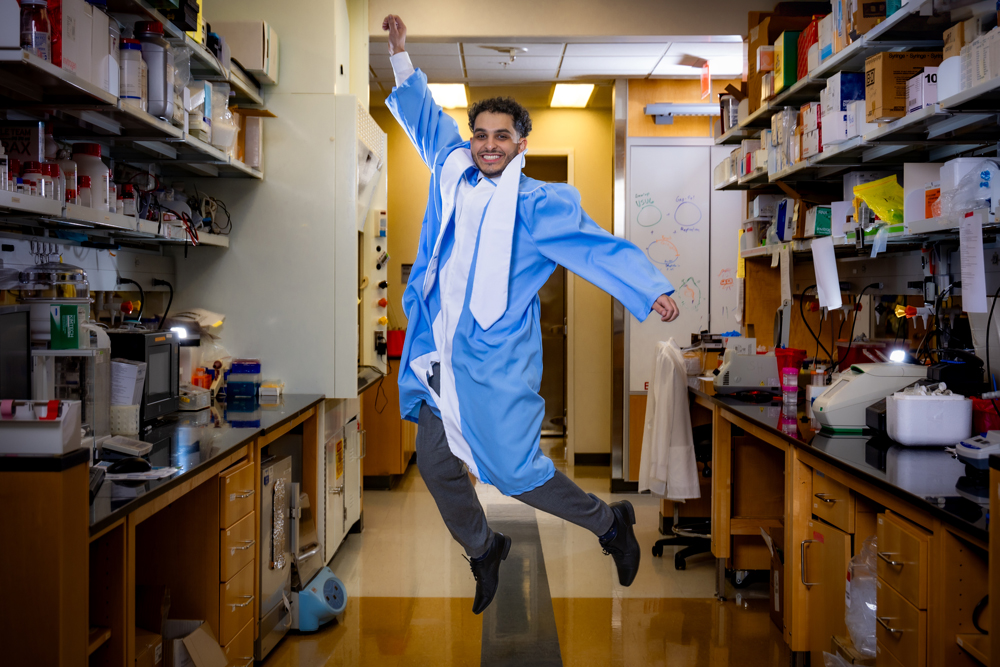

Rami Darawsheh | health policy and management

photo by Megan Mendenhall

photo by Megan Mendenhall Before coming to Carolina, Rami Darawsheh thought research was repetitive and closed off — an activity where people didn’t work together. But he soon realized this was not the case.

“I was surprised how collaborative research is. Everyone works together and is willing to help you,” he says.

As a first-year student, Darawsheh knew he was interested in studying medicine, but he wanted to use his time at college to reaffirm this interest and explore adjacent fields.

In 2022, he joined the Hingtgen Lab, which focused on developing more effective drugs to treat brain cancer. This includes using a brain-slice model and developing a scoring system based on how effective the drugs are at killing the tumors and how harmful they might be to the brain.

The typical standard of care for brain cancer is to treat the tumor with a specific drug based on what type of genetic mutation the biopsy shows. But biopsies may not represent the entire tumor, making it difficult to determine which drug might be most effective in targeting and killing the cancer cells.

With the brain-slice model, researchers can use a cell line from a patient’s cancer to test a drug and then watch how it reacts.

“They had a library of 10-plus drugs. Some of them were still undergoing clinical trials and a lot of them were new-generation, targeted therapies — things that I have never even heard of before,” Darawsheh says. “It was an exciting opportunity.”

Darawsheh also worked with Colette Shen’s group in the UNC Department of Radiation Oncology, using electronic health records to uncover when patients received a certain treatment and documenting whether they had follow-up appointments.

This information helps clinicians optimize their standard of care by providing insights into how patient statuses change over time. It can also determine if treatments should be reevaluated or removed.

Through his work in the radiation oncology department, Darawsheh developed the idea for his honors thesis: a retrospective analysis of neurological outcomes for patients who have had whole-brain radiation. While this can be an effective treatment for getting rid of the cancer cells, it can also leave patients with negative, long-term neurological outcomes and poor quality of life.

Darawsheh hopes his project will provide insight into how these patients’ neurological statuses change over time and will help other researchers evaluate the effectiveness of this treatment.

“These kinds of projects are super interesting to me because I get to do a deep dive on the patient’s history and understand what happened to them throughout their treatment,” he says. “I feel like I’m able to make a difference.”

Before starting medical school at the University of California San Francisco this fall, Darawsheh plans to travel to Jordan on the Phillips Travel Scholarship. He’ll gain insight on how the health care system there is handling the refugee crisis and addressing health care disparities within its population.

“I feel like everything I’ve learned at Carolina translates to research,” he says. “It translates to what I want to do in medicine and adjacent to medicine, whether that’s working in policy, continuing to do research, or working with practice-based, public health initiatives.”