Quiche Lorraine. French onion soup. Cheese souffle. Boeuf bourguignon. These are just a few classic French dishes found in “Mastering the Art of French Cooking,” Julia Child’s first-of-its-kind cookbook to bring French cuisine to America in 1961. This book, according to historian David Strauss, “did more than any other event in the last half-century to reshape the gourmet dining scene.”

While French cooking has long been applauded as the best of the best in the food world, the culture’s sustainable food practices are lacking. At least, that’s what UNC senior Savannah Faircloth found when traveling in Paris last summer as the 2019 Carolina Global Food Program’s Summer Scholar. Each summer, the program sends a student to a location of their choice to help them achieve a research goal related to food studies.

What surprised Faircloth was how American food practices have found a devoted audience in France. “The organic food movement in [urban] France is heavily influenced by the American organic food movement,” she says. “Social media plays a big role in this. French people can see what’s happening in the U.S. and apply it to their cities.”

Faircloth decided to pursue a project on Parisian food markets after taking French 286, a class exploring how food culture penetrates all aspects of French society. She wanted to know how these spaces act as microcosms of French culture and reflect changing food patterns, politics, and identity.

Just as Julia Child hoped to translate French cuisine in her cookbook, Faircloth strives to show the cultural phenomena she observed in Paris through hand-drawn portraits. She chose drawings as her medium to match the slow thoughtfulness of creating images on paper with the idea of “slow food.”

Savannah Faircloth was inspired to draw visitors in Parisian food markets after taking a French course. Photo by Matthew Westmoreland.

“In a world where we can take a billion photos on our phone, I think putting the time and thought into drawing one thing makes something more important,” Faircloth says. “In the same way, if you go to a dozen fast food places, you can get anything in minutes but that removes some of the labor and care that goes into making a more meaningful meal.”

Faircloth’s appreciation for slow food would only grow after she returned from Paris. In Fall 2019, she enrolled in Eats 101, a unique interdisciplinary research-based course that features regular field trips like visits to local farms and food producers. At the end of the course, students investigate research topics based on their own food interests.

The course has flown somewhat under the radar since it was first offered in 1997 — and food studies program heads James Ferguson and Samantha Buckner like it that way, says Faircloth, who learned about the class from to a friend.

As she finishes her drawings from Paris, Faircloth has discovered new inspiration from the experiences she had in Eats 101. She and her classmates had dinner at their professor’s house every Tuesday and, occasionally on Thursdays, they would go out to local restaurants.

“Food is a basic necessity for all of us, but it has the capacity to be so much more than just fulfilling that necessity,” Faircloth says. “It can be art. It can be meaningful when you share it with someone you care about. Food is an interesting focal point around which we can talk about other issues.”

France’s urban farms

France has gained worldwide fame for its farming history. While Gruyère, Camembert, Brie, and Roquefort are cheeses with household names today, each began life in small French communes and towns with proud agricultural heritages, one that includes a healthy tradition of activism. In November 2019, farmers rode 1,000 tractors into the heart of Paris to protest new regulations under French President Emmanuel Macron’s government that, they believe, stifle the industry.

Despite some friction with farmers and agricultural workers, though, France’s strict enforcement of environmental regulations earned the country a number-one spot on the 2018 Food Sustainability Index, a ranking system formed by the Economist Intelligence Unit and the Barilla Center for Food & Nutrition Foundation. The United States failed to break the top 20.

Paris visitors will likely encounter street markets with rows of fresh fruit and vegetables as they navigate the city — environments that American tourists often mistake for farmers’ markets, Faircloth says. “If there’s food in a stall, we tend to assume it’s from a local farmer because that’s how most Americans encounter fresh produce outside supermarket chains.”

That’s not often the case in Paris today, where much of the food sold in curbside markets comes from outside the city from major distributors like Rungis, the largest wholesale food market in the world and a vital network for the French food scene.

Because of its proximity to Rungis and the legendary creativity of chefs like Paul Bocuse, Jacques Pepin, and Alain Passard, Paris has become a mecca for foodies craving world-class culinary experiences. In its urban form today, Paris isn’t exactly synonymous with agriculture. Before the 20th century, though, the French capital was home to at least 500 urban farmhouses, which supplied milk and other produce to the city’s residents. Now, only one dilapidated farmhouse, Ferme Montsouris, remains as a monument to the city’s urban farms.

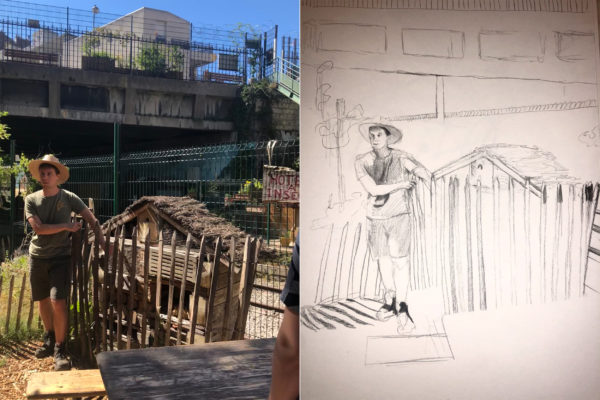

Faircloth hopes to convey this history in her project. To do this, she recorded interviews with people from the food industry in Paris, took their portraits on her phone, and then made sketches of the area where she met them so she would have a basic outline to work with when she returned to the U.S.

Savannah Faircloth took photos on her cell phone while in Paris, and then used those later as references for her drawings. Photo courtesy of Savannah Faircloth.

Susan Kutner, one of Faircloth’s subjects, is a former private chef for Marc Jacobs and now operates an association for the maintenance of peasant agriculture (AMAP). These are community-supported agriculture models that connect business clients, like restaurants, exclusively to small local farms to help provide them with a steady income.

The French, according to Kutner, seem less conscious of where their food comes from because Paris has lost its historic connection to neighborhood food markets like the farmhouses. She feared that Parisians would be less receptive to organizations like co-ops or her AMAP, but young adults appear to be taking up the farming mantle that was once a jewel in the city’s crown, even if it means growing gardens on rooftops.

With a growing network of urban farms in Paris, the city’s residents “can reduce the amount of energy it takes to distribute the food and have the food come from the center of the city,” Faircloth says.

Faircloth’s other subjects included a visitor at a rooftop garden pilot project designed to encourage similar projects elsewhere in the city, and an employee of La Recyclerie, an urban farm that brings produce to nearby restaurants to reduce transportation waste.

Food for thought

During Faircloth’s Eats 101 class, she also learned about the relationship between science and food, particularly when it comes to medicine, and had to distill her experiences into a research topic. As a senior who hopes to attend medical school, Faircloth saw this as an opportunity to discuss food as a public health issue.

Her research focused on doctors like Mona Hanna-Attisha in Flint, Michigan, who prescribes food as a remedy to combat lead toxicity in the water. “She worked with nutritionists to establish a food market next to her pediatric clinic,” Faircloth explains. “They can prescribe food and then have them go straight to the food market to get what they need.”

Hanna-Attisha, who helped expose the lead crisis in Flint, created the program in 2016 to combat childhood lead exposure by mandating a healthy diet. Her work, according to Faircloth, is grounded in recent research which suggests that prescribing food to patients will make people more likely to seek out those products and develop healthier eating habits.

Overall, Faircloth’s summer in Paris and the Eats 101 course helped her find new meaning in food. “It’s inspiring to see the way that [people] integrate food and sustainable practices into their lives.”