On a warm summer day in Salona, Croatia, Michelle Freeman walks under an eroding archway and pauses, in awe of her surroundings. She is greeted by a menagerie of sarcophagi, some so large they cast a shadow over her, others so crumbled they’re nearly unidentifiable. If she’d visited this ancient Christian basilica in the fourth century, the area she’s currently standing in would actually be underground. As she heads further into the necropolis, she comes upon a tomb with a small, closed-off cavity underneath it.

“It’s clear this was something special,” shares Freeman, adding that historians believe this to be the tomb of Saint Domnio — a bishop martyred under the emperor Diocletian in the early fourth century.

“Visiting Manastirine was kind of an ethereal experience — to see all the layers of the cemetery and the church built on top of it,” she says.

Manastirine’s layers date back to the Hellenistic period. That’s two centuries before Christ was born. The basilica was built over the graves much later.

The remains of Manastirine, a fourth-century cemetery basilica in Salona, Croatia. (photo by Michelle Freeman)

Freeman, a UNC-Chapel Hill PhD candidate in the Department of Religious Studies, spent two weeks this past summer traveling across Croatia, North Macedonia, and Greece to visit cemeteries like this one for her dissertation. She strives to improve understanding of how saints were venerated in the fourth century and studies this by analyzing the homilies that were preached on their feast days within these spaces.

“I’m motivated by the fact that we should try to understand each other religiously,” Freeman says. “Because we all interact with religion, spirituality, or ethics in some way, whether we recognize it or not.”

Drawn to ancient disputes

Freeman became interested in religious studies as a history major at The Ohio State University (OSU). During her second semester, she took a class on ancient Christianity, which opened her eyes to the diversity within the religion at that time.

“I had no idea there were so many varieties of Christian theology, ritual, and behaviors that were sometimes coexisting and sometimes competing for supremacy,” she shares. “The ‘winners’ might call [their competitors] ‘heretics’ or think that they were unimportant because they died out, but in reality, these were large and significant groups of Christians whose stories we can try to tell based on the texts and remains they have left behind.”

After that class, Freeman hit the ground running. Alongside her fascination with religious studies, she realized she wanted to pursue a career in research and began working with David Brakke and Bert Harrill, historians of Christianity at OSU. In her sophomore year, she began taking courses in Greek and Latin to learn how to translate texts and, by the following summer, received a Libraries Research Fellowship for a project on Christian attacks against heresy.

Freeman’s husband stands next to one of the giant sarcophagi from Manastirine for scale. (photo by Michelle Freeman)

“In the first three centuries, Christians are all fighting with each other: You’re wrong. You’re wrong. No, you’re wrong. And some of it actually had to do with debates over whether or not they should be venerating saints. That’s how I became interested in the topic.”

Revering saints was seen as problematic because some people thought it looked a lot like paganism — a term used in the fourth century to denote non-Christians who believed in multiple gods.

To study these practices across the Mediterranean and Near East, Freeman has since added German, French, Syriac — the language of ancient Syria — and Coptic, the last language spoken by the ancient Egyptians, to her repertoire. Grasping these languages makes her research easier to conduct and opens the door to studying Eastern Christianity, which is more neglected among scholars, according to Freeman.

“I’m trying to understand how we can step back from our particularly Western assumptions about other groups of people and to try to engage them,” Freeman says. “Our country is becoming more globally diverse, and it’s not going to go well if we can’t grasp ideas that are so fundamental to other cultures. And saint piety is fundamental to well over half of the Christians in this world, and Western scholarship, I think, fails to understand it.”

A dispute of her own

For the religions that recognize them, saints were once people considered to have exceptional holiness, likeness, or closeness to God. In Catholicism, people become saints through canonization — a public ceremony led by the pope that involves the sacrament of communion and entering the person’s name into the formal list of saints, called the “canon.” The Eastern Orthodox Church calls this process glorification.

Freeman studies how Christians from the Mediterranean and Near East revered saints in late antiquity, the fourth to sixth centuries. This topic intrigues her for a few reasons. First, many religious studies scholars have historically focused on Western Europe, rather than the eastern part of the world.

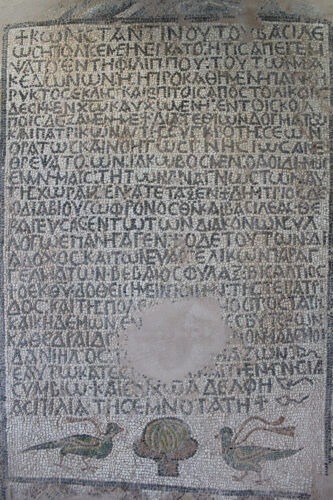

A mosaic floor epitaph from a cemetery in Philippi, Greece, for a priest named Daniel, who was born in Constantinople. (photo by Michelle Freeman)

“Saint veneration is something I feel is extremely misunderstood in popular culture and scholarship,” Freeman says. “So much of it is western-centric, focused on Latin sources, which are the basis for later western Catholic and Protestant traditions. It’s only recently that materials in Greek, Coptic, and Syriac — the foundational languages of the Eastern and Oriental orthodox churches — are being translated and discussed.”

The fourth century was an interesting time in religious history, according to Freeman. Clergy began centralizing worship in churches, but congregants continued to visit local shrines and cemeteries for prayer. Current religious studies scholars argue that bishops strived to control the veneration of saints by bringing their remains into churches, creating tension with members of their congregation, who preferred to practice piety in more traditional and familiar spaces. Freeman doesn’t buy into this theory.

Oftentimes, while standing in the ancient cemeteries she visited this summer — which contained the tombs or remains of saints — Freeman could see the churches inside the city walls sitting just a few hundred meters away. Members of the clergy and the public were put to rest in these cemeteries and both parties also contributed to their construction, according to inscriptions at the sites.

“It screams cooperation to me,” Freeman says. “Not tension and not control.

“Funerary cult is one of the most prominent types of ritual activity we have evidence for in antiquity,” Freeman adds. “People ate meals by graves. People went there yearly to visit deceased relatives. People were in these places all the time. And it seems far-fetched to me, based on proximity of the churches and the evidence that clergy and laity shared these spaces, that there was some sort of tense relationship around these cemeteries that I think everyone visited.”

Back in Chapel Hill, Freeman continues to tackle this topic by delving into underexplored yet incredibly valuable resources: homilies preached by bishops to congregations in churches and at shrines on the feast days of saints. Many of these texts have only been translated in recent decades, so few scholars have studied them. For Freeman, these homilies suggest bishops actually encouraged their listeners to keep with tradition by visiting shrines and celebrating on feast days.

Freeman believes that the more we understand these ancient cultural practices, especially the understudied traditions of Eastern Christianity, the more we’ll understand how those cultures have evolved today. Personal values, celebrations, and war all often stem back to religion.

“I’m simply trying to understand people’s behavior from sociological and anthropological perspectives,” Freeman says. “It all goes back to being able to responsibly engage the diverse perspectives of the world we live in.”