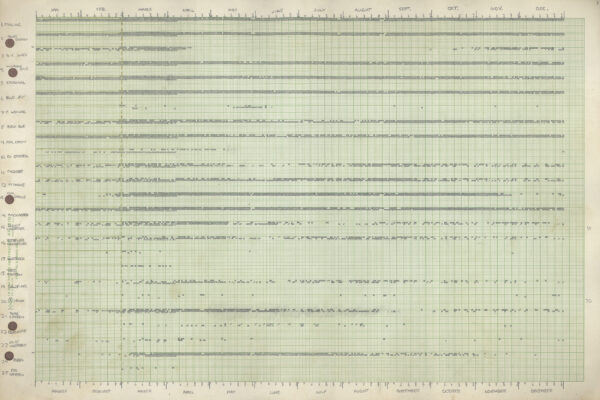

Each day for two years, between the ages of 12 and 14, Alan Weakley wrote down every single bird he saw. He recorded his observations on graph paper, including the species, date, and number of birds. He didn’t do this for a school project or a Boy Scout badge. He didn’t do it to appease his parents or a bird-loving grandfather. He did it because it fascinated him.

“Even when I was a kid, I was really into classifying information and making lists and things like that,” he says.

Weakley would often ask his older brother Doug to give him a topic he could research and create an informational chart for. He did this once for all the planets and moons, happily spending hours with his nose inside an encyclopedia.

Today, Weakley is an established conservation biologist at UNC and the North Carolina Botanical Garden — and he’s spent the past 30 years turning his observations into useful, organized information. More specifically, he developed the “Flora of the Southeastern United States,” an identification guide for plants spanning from Pennsylvania and Florida to the eastern part of Texas and Oklahoma. It includes extensive information about the taxonomy, habitats, geographic distribution, and rarity or invasiveness of each plant.

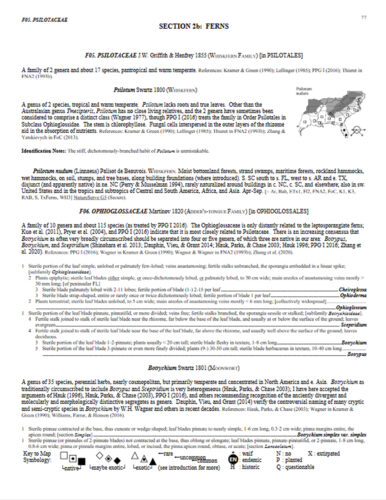

“A flora is not just an encyclopedia or a set of pictures,” Weakley stresses. “It is a set of keys that gives you an organized means of identifying the plant you have in your hand. It asks a series of questions: Are the flowers white or red? Are the leaves opposite or alternate? So you go through this list of dichotomies to come to an answer.”

Weakley’s work is vital for plant conservation, ecosystem monitoring, and educating the next generation of biologists. What’s special about this particular flora is that it’s not a physical thousand-page tome — which, as one can imagine, is difficult to bring into the field. It’s completely online, making it incredibly accessible to not only conservationists, biologists, and natural resource managers, but also citizen scientists, farmers, and middle- and high-school students.

“There’s an old saying about floras,” Weakley says, chuckling. “Floras are written by people who don’t need them for people who won’t be able to use them. I try to work against this idea.”

Since “Flora of the Southeastern United States” went online in October, it’s been downloaded nearly 4,000 times — a far greater number than the amount of physical textbooks that would otherwise be purchased, Weakley says. What’s more, Weakley receives daily emails from colleagues and the general public about the plants they find and potential updates to be included in the flora, which he lovingly refers to as a “creative compilation.” More than 500 collaborators from across the region have added to its pages.

“I am not a godly oracle who is giving you perfect information,” he says. “I am compiling and working through and developing and constantly trying to improve the information. And I can do that best with feedback from users.”

With 4,000 plants in North Carolina alone, how does one even begin to embark on a project so large? One page at a time.

A flora is more than just a book of plants. It is an encyclopedia that includes extensive information about the taxonomy, habitats, geographic distribution, and rarity or invasiveness of each plant featured. This page from Weakley’s flora is the introductory page for ferns. (screenshot from “Flora of the Southeastern United States”)

Discoveries and digitization

Before coming to UNC, Weakley worked as a botanist for the North Carolina Natural Heritage Program, cataloguing rare plants across the state. It was the mid-1980s, and the most up-to-date flora at the time, “Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas,” was already two decades old. And a lot of new discoveries were being made.

“Heritage Program biologists were finding new plants that weren’t known to be in the Carolinas before,” Weakley says.

To fill in the blanks, Weakley began writing supplementary keys to the 1968 flora. By the time he came to UNC in 2002, he had begun compiling a working draft of a flora for the Carolinas, Virginia, and Georgia — a project that would eventually evolve into “Flora of the Southeastern United States.”

When Weakley joined UNC, he began working as a curator for the herbarium. Today, the UNC Herbarium houses the nation’s largest collection of southeastern plants.

“Herbaria are kind of amazing things,” Weakley says. “They’ve been accumulating for hundreds of years all of these specimens that document the plant life of the world (and museums, the animal life). It all seems very dry and dusty and 19th century to a lot of people.”

But herbaria have moved into the modern world, Weakley points out. Advances in DNA sequencing in the early 2000s, for example, have helped botanists uncover an array of new information about plants from evolution to food production. One of Weakley’s goals since becoming director in 2006 has been to digitize all of UNC’s specimens. He and his team have spent the last decade photographing each one and uploading them into an online repository.

In 2015, Weakley released an app he developed with database expert Michael Lee and app developer Rudy Nash called FloraQuest. It is a digital version of his earlier work, “Flora of the Southern & Mid-Atlantic States,” and is intended to make plant identification simpler for both scientific and general audiences.

Community contributions

Weakley has acquired funding to make his most recent flora available in apps that will include pictures of each species. Engaging a broad audience is a high priority for him. Fellow researchers and citizen scientists are essential for growing the flora over time — and for helping conserve a region’s plants.

“Our smartphones have an amazing ability to sort information that make identifying plants easier than it used to be,” he says. “There are a lot of people out there who are just interested in documenting their plants in their backyard or the county park down the road, so they need resources to ID plants, too. I want to keep people interested in the natural world.”

Literally hundreds of people continue to send Weakley emails with observations that he incorporates into the flora. Some come from local hikers or green thumbs who’ve discovered a particular plant they’d never seen before. Others are from people in the scientific community, such as fellow researchers, conservationists, and park rangers.

“Any flora, in essence, is a collection of other people’s work combined together and summarized by an author or multiple authors,” says National Park Service botanist Forbes Boyle, who uses the flora to monitor vegetation and verify species within specific locations. Unlike other floras, he says, Weakley’s “feels different — like the spirit of both contemporary and historical botanists are alive and present throughout, like Alan is giving them a stage to mingle together and communicate to the reader.”

Mac Alford, a professor and herbarium curator for the University of Southern Mississippi, makes the flora a required resource for his students and appreciates that it’s a free supplement they can utilize alongside their textbooks. He has sent Weakley feedback about ways to improve this “vital resource.”

“The thing I like about Alan’s flora is that he is constantly updating it and making it freely available,” he says. “He has also been generous with sharing data, despite getting little back in return.”

Lesley Starke, manager of the North Carolina Plant Conservation Program, uses the flora to identify and protect at-risk species. She appreciates that she can load it onto a tablet for use in the field.

“Anyone can have a physical book with them — and many do — but the ability to receive frequent updates, plus new features, makes botanical field work easier and more efficient,” she says. “Alan has no shortage of experience in the field, so for him to not assume what the users want and need and to actively seek their input and suggestions is great.”

There is a constant flow of new information about plants that can be difficult to stay on top of without feedback from others, Weakley says. That’s why he will spend the rest of his life working on “Flora of the Southeastern United States.”

“I think there’s a lot of urgency to the information that’s in floras,” he shares. “From knowing that one plant is edible and another is poisonous, that a specific plant is going to cause economic damage, or understanding the diversity in a park or natural area that you’re trying to maintain. It’s making all of the accumulated information from museums and scientific papers and so forth useful in a practical way.”