Suzanne Lye walks along a raised path and watches archaeologists below painstakingly uncover wall paintings that are thousands of years old. One of the most important prehistoric settlements in the Eastern Mediterranean, the ancient Minoan city of Akrotiri is rife with pock-marked stone walls and beat-up window frames — a stark contrast to the white, smooth, blue-roofed clay homes that cover the island community of Santorini, Greece.

“It was just incredible to be in that space,” she recalls. “To think about who lived there and created this beautiful art, what it was for. I just found that I wanted to spend more of my time thinking about that.”

Suzanne Lye, an assistant professor in the Department of Classics, decided to pursue a career studying ancient texts and artifacts after a trip to Greece in 2002. (photo by Katie Gibbs)

When Lye took a trip to Greece in 2002, she decided on a whim to stop by the local tourist destination. At the time, she was working in the California tech industry as a project manager and product developer and was thinking about applying to graduate programs to study organic chemistry. Shortly after visiting Greece, though, Lye dove back into academia — and traded in her industry job and laboratory equipment for ancient texts and artifacts.

This career shift was not wholly spontaneous. It was built upon Lye’s lifelong interest in the ancient world. Like many of her current students, she first encountered this realm in elementary school through Greek mythology and later through Homer’s epics, “The Iliad” and “Odyssey.” Today, Lye is an assistant professor in the UNC Department of Classics, presenting her first-year seminar students with unique perspectives of the ancient world.

In a recent class, Lye discussed love magic and the age-old equivalent of relationship advice columns. She pointed out that people in the ancient world had the same relationship squabbles people have today, but rather than buy ice cream for a broken heart, a person in Ancient Greece or Rome might head to the marketplace to buy a love potion or spell book. The latter offered ancient peoples solutions to longstanding questions faced by men and women alike: How do you keep a lover interested? What happens if a man can’t perform? How do you get someone to notice you instead of someone else?

In her seminar course, “Ancient Magic and Religion,” Lye’s students study how ancient Greek and Roman societies used these magical objects and texts to influence their lives and the lives of others. Sources used in the class include curse tablets, love charms, and material artifacts like amulets, talismans, dolls, and papyri.

Lye is a philologist, so she studies ancient Greek and Roman language and literature for her research. But in her newest project, as in her class, her scope has expanded beyond literature and linguistics to include comparing ancient stories with real archaeological artifacts.

Both her research and course center around the fantastic — magic, spells, curses, the underworld — but Lye stresses that rather than estrange us from the ancient world, studying these practices, beliefs, and stories can help connect us to these long-dead people.

Classical world, classic problems

Lye knows what it is like for her students to enter the ancient world without a lot of established knowledge. As an undergraduate at Harvard University, she pursued a degree in organic chemistry and the history of science.

Lye didn’t have the opportunity to learn Greek until after college but had taken Latin for a few years in high school. As a latecomer to the humanities, she feels armed with a diversity of real-world experiences — and uniquely equipped to challenge students’ assumptions about the ancient world and its relevance to modern life.

“My family are immigrants. I’m an immigrant. I am not from a wealthy background, and I haven’t always read or had exposure to the canonic texts of high literature,” she explains. “But I learned a lot about storytelling from my grandmother, who spoke a different dialect of English.”

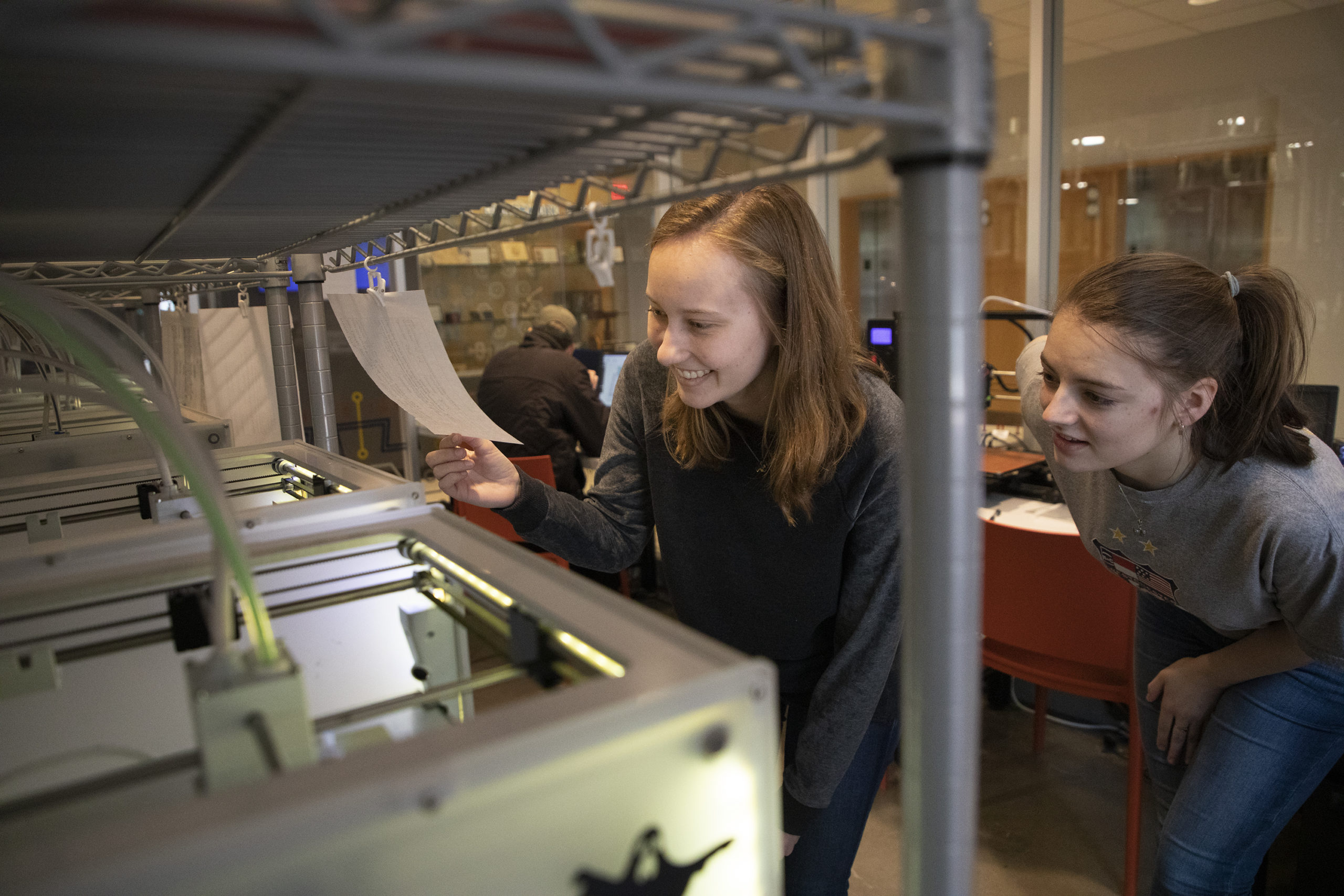

Lauren Behringer and Isabella Behrend watch as Behringer’s 3D replica of an ancient amulet prints at the BeAM Makerspace. (photo by Megan May)

Students in “Ancient Magic and Religion” are taught to view ancient people as deeply human, complex individuals, rather than two-dimensional men etched into pottery. They had relatable issues that they addressed with their own traditions. They got sick, but rather than cough drops, they bought a votive offering to treat sore throats. They had rivalries, but instead of blocking people on social media, they purchased a curse tablet.

Her students come to see how their lives mirror those of these long-gone people. This theme is a point of emphasis in the classics department, where classes are focused on investigating the fundamental issues confronting people then and now and understanding our place in the world through the worlds of others.

Humans have always entrusted hopes and fears, in some way or another, into sacred objects or special words. A protective amulet sounds crazy, but what about a lucky penny? The ancient curse tablets and spells that Lye encounters in her research and presents to her students in class come alive through her multidisciplinary approach to the course.

“When you just read the text in a modern book, you don’t really get a sense for its visual impact or social impact,” she says. On any given day, her class can be found in the BeAM Makerspace, the Ackland Art Museum, the Greenlaw Gameroom, and various libraries. Lye uses as many campus resources as possible for two main reasons: to make these ancient stories, peoples, and magic less foreign to students and to introduce them to Carolina’s hidden gems.

Craft as the Romans craft

In the BeAM Makerspace, Lye’s students design and create replicas of ancient magical objects like protective metal amulets, 3D printed votive offerings, scrolls of papyri with spells, or wooden funerary vases painted with traditional images. The information they inscribe onto these objects — such as talismans with binding spells or engraved curse tablets — range from personal designs to copies of ancient figures and texts studied in the class.

Students are given creative freedom in Lye’s “Ancient Magic and Religion” class, creating artifacts like inscribed boxes, talismans, texts, or even videos. (photo by Megan May)

Lye strives to challenge her student’s assumptions about the ancient world. When they recreate objects from class, she says, they reflect on how people interacted with these objects thousands of years ago. If a replicated tablet is heavy, they may start to wonder how people carried them around. When an engraving process in the BeAM Makerspace proves challenging, they consider the craftsmanship of the real artifacts as well as the materials and technologies available to ancient people.

Lye still has some of her favorite products from previous classes. One surprising standout, she says, is a battered-looking brick. It was inscribed by a group of students with a spell designed to bind Lye to giving them an A in her class. Today, she uses it as a paperweight. Besides being incredibly entertaining, Lye found their project represented the effort, mistakes, former lives, and alternate uses that often characterize the objects the class studies.

“This was very true to how people in the ancient world would reuse material,” Lye says. “If somebody found a piece of pottery or other things that people might throw away, they could use that and write a spell on there. It’s ancient recycling.”

New eyes to ancient ideas

Recently, there have been a lot of new publications on magic and the ancient world. But, Lye points out, many of them are only translations. Her own skills lie in reading between the lines, asking new questions, and challenging assumptions.

In both her nearly completed book on the ancient Greek underworld and her upcoming project on ancient women and anger, Lye analyzes texts in ancient Greek and Latin with special attention to details she feels previous academics may have regarded as “throwaway lines” or unimportant descriptors.

“This line meant something to somebody,” she points out. “What did it mean? What is it telling us about their life and relationships?”

The women that Lye focuses on now can often be found in epic poetry and ancient plays — tragedies and comedies – typically written by male authors. These stories feature powerful, angry women who cast spells or seek divine retribution against their husbands.

Lye has always liked to direct her focus toward the often-overlooked people on the margins of ancient narratives, like these women or people in lower social classes. Her past research has explored relationships between ancient men and women, epics and everyday life, conceptions of life and death, and representations of gender and ethnicity.

“You can tell things about the society in which a hero or major character lived by seeing how other people around him interacted and operated,” she says. “Showing my students these subtle interplays between characters and their environments is a highlight of my job as a classics professor.”