Imagine having to tell a patient there is nothing you can do to help them. For years, the only option for doctors treating pancreatic cancer was to prescribe chemotherapy, leaving most patients without a cure and limited improvements to their quality of life.

Jen Jen Yeh uses her skills as both a physician surgeon and researcher to develop tools and tests to close those gaps in endocrine, melanoma, and pancreatic cancer patients’ care through the UNC Department of Surgery and Pharmacology. While it can be challenging to maintain a thorough understanding of both fields, she believes the two careers are complementary and – with the right balance and time management – synergistic.

“Physicians go into surgery in particular, because there’s a lot of short-term gratification in helping patients,” she says. “But we develop long-term relationships with the patients too as we try to understand their disease process.”

For Yeh, it’s not just about the operation, but about making sure that a patient has the best quality of life and outcome after surgery. Mark Byerley, a 62-year-old patient from Greenville, South Carolina, had a neuroendocrine pancreatic tumor, one that grows far slower than most pancreatic cancers Yeh works with. After seven years of monitoring the tumor with imaging, Yeh and UNC endocrinologist Elizabeth Harris determined it was time for surgery. While he knew this day would come, Byerley felt reluctant and worried about the risk of getting diabetes.

“It was through [Yeh’s] patience, listening to my concerns, and explaining to me why surgery was necessary right then, that I began to understand,” he says. “It was a tough decision. I wanted to preserve as much of the pancreas as possible so I wouldn’t become diabetic.”

While imaging alone did not give Yeh a clear enough understanding of the tumor to make any promises about being able to keep his pancreas, Byerley said he trusted her to respect his wishes and do all that she could in surgery because of her honesty and communication.

“I wanted to add life to my years, not years to my life,” Byerley says. “Dr. Yeh under-promised and overdelivered.”

Byerley believes Yeh has added more than a decade to his life, giving him opportunities to take hiking trips to Maine and live a healthier existence. Receiving milestone updates and “thank you” cards on Thanksgiving from patients like Byerley years after they’ve been discharged are moving reminders to Yeh that she’s made a difference in their lives.

“I don’t think I’m going to cure cancer,” she says. “But what are the baby steps that I can take to overcome hurdles in the clinic and actually help patients?”

Navigating two worlds

In 1991, shortly after completing her undergraduate degree, Yeh worked as a research technician at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston. There, she was surrounded by doctors and researchers focused on treating cancer and finding new ways to help their patients. Working in this environment was inspiring, Yeh says — so much so that she came back to Dana-Farber in 1998 as a research fellow during her general surgical residency at Boston Medical Center.

“They were tremendous role models for me in terms of being rigorous, translational scientists who really thought about scientific integrity and clinical impact at the same time,” Yeh says.

One of those role models and mentors was William Kaelin, the 2019 Nobel Prize recipient in medicine or physiology. Yeh describes Kaelin as simultaneously intimidating, brilliant, inspiring, and demanding.

“He had very high expectations and a single-minded dedication to medicine and science,” Yeh says. “That challenged me to be the very best that I could be.”

Yeh continues to reflect on these experiences in the clinic and lab today.

Translating from lab to clinic

Not long after Yeh joined UNC in 2005, a colleague introduced her to entrepreneur and chemical engineer Joe DeSimone. Along with UNC medical student James Byrne, DeSimone had developed a new drug-delivery device, and they wanted Yeh’s help to put it to clinical use.

While the device can be used anywhere and with virtually any drug, Yeh’s first thought was to use it on patients with inoperable pancreatic tumors. Often times with pancreatic cancer, the tumors wrap themselves around blood vessels, making it impossible to remove the tumor without also killing the patient. This leaves them with no real cure —only chemotherapy treatments that subject their whole body to the draining effects of the drugs. Yeh realized the new precision-delivery device — which uses an electric field to drive drugs directly into a tumor — could help overcome those issues.

“It really hit me that if we could just shrink the tumor away from the vessels enough, then we can go in and take out it out,” Yeh says. “Chemo is nondescript: It kills the tumor, but it kills other things, too. The device just kills the tumor and leaves the rest of your body alone.”

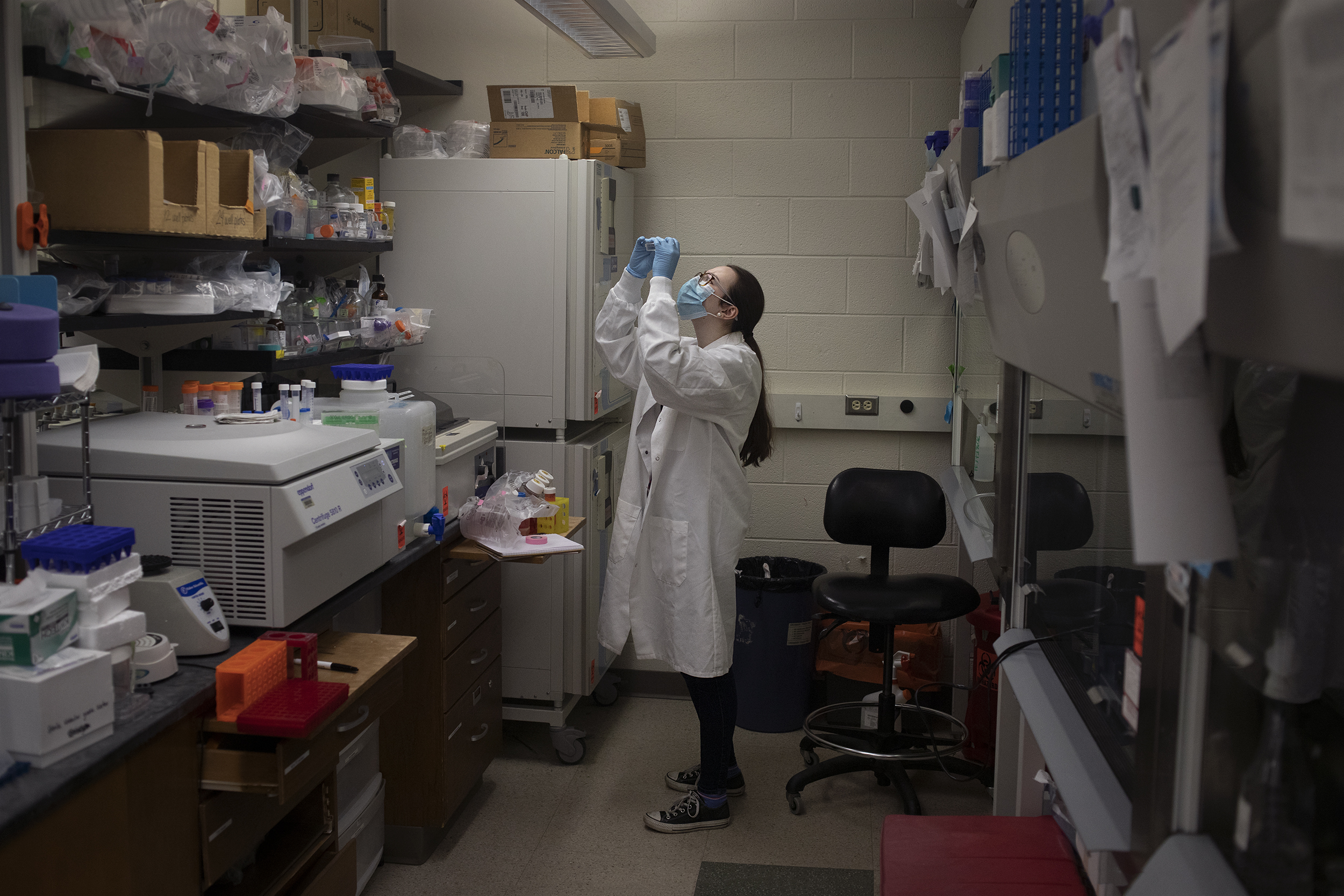

Mariaelena Nabors, a PhD student, checks the status of cell growth in patient-derived pancreatic cancer cells in Yeh’s lab at the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center. (photo by Megan May)

By implanting the device on a tumor, chemotherapy drugs can be administered directly into the cancerous growth, rather than subjecting the entire body to the drugs with intravenous treatments administered through the bloodstream. In fact, rigorous testing of the device on resilient, tough-to-shrink tumors in pre-clinical studies showed that the drug did not enter the bloodstream at all.

“I was shocked and very circumspect in my optimism because we hadn’t seen these kinds of responses in pancreatic cancer tumors to date,” Yeh says.

With this more precise approach, not only did the team find unprecedented levels of pancreatic tumor shrinkage, they also realized the device would open doors to the use of drugs previously deemed too toxic because they would impact the patient’s entire body. The findings reassured Yeh that the device would be worth translating to clinical use in humans.

“This is the part they don’t teach you,” Yeh says. “It was a learning experience for me to start to recognize that you can have something in the lab that you think is totally promising and is going to work, but now how can you get it to the patients?”

Yeh felt compelled to become an entrepreneur and with the help of DeSimone, Advanced Chemotherapeutic Technologies, Inc. was founded. While COVID-19 has caused some delays, they are hoping to begin a small, first-in-human study at UNC in 2021 and then expand clinical trials to multiple institutions.

Genomic matchmaking

Yeh’s current research seeks to continue to close gaps in care by focusing on cancer biology and genomics, the study of all of a person’s genes. Her lab has discovered genomic markers for subtypes of pancreatic cancer that do not respond to the standard therapies given at UNC and across the country.

“Our hypothesis is that people who are in this specific group should look at alternative therapies,” Yeh says. “If we get to patients earlier before they start treatment, we can match them to the best therapies from the start.”

After Yeh and her team develop a hospital-based assay at UNC, researchers at Medical College of Wisconsin and Honor Health in Arizona will run a clinical trial to determine if her hypothesis is correct. If it is, oncologists will be able to better match patients with the most effective treatment and, hopefully, provide them with improved care and quality of life. The team plans to start the trial by the end of 2020.

RNA sits in a tub of ice (left) while being prepared for RNA sequencing, and Petri dishes (right) containing patient-derived pancreatic cancer cells sit in a laboratory hood in Yeh’s lab. (photo by Megan May)

Being at the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center provides Yeh with phenomenal opportunities to do research like this and work with other specialists to provide the best patient care possible, she says.

Yeh mentions with relish how easy it was in pre-COVID-19 times to simply walk over to a colleague’s office, knock on their door, and swap and share ideas concerning their work. While that collaborative environment is complicated by virtual platforms like Zoom, the persistent collegial culture that exists at UNC is one Yeh says was crucial for her development as a junior faculty member. From early on in her career at UNC, Yeh recounts the genuine interest, support, and openness she received from experienced senior physician scientists.

“The low-stone-wall culture at UNC is really helpful,” she says. “When Joe DeSimone reached out to me, I was young, and Joe was already pretty famous in his own right. To have somebody like that just reach out to you and want to talk to you is amazing. I think that’s part of the culture at Carolina.”

Collaboration and mentorship play important roles in the culture Yeh cultivates in her lab as well. Despite her busy schedule as a researcher, surgeon, and mother, Yeh still manages to have weekly one-on-one sessions with her students.

“That really shows just how committed she is to her mentorship,” Maddy Jenner, a second-year graduate student studying pharmacology, says. “The quality of research I’m doing now will definitely inform my research down the line, and Jen Jen is always feeding us opportunities to expand our knowledge base and skillset.”

Like Jenner, Jack Leary, a UNC statistics and analytics major who graduated in Spring 2020, says his time in Yeh’s lab has transformed his career path. After he began working in the lab his junior year, Yeh developed a special student research position for him to apply his skills in data analytics to cancer research.

“She’s an incredible person,” Leary says. “No one in my family is an academic, but Jen Jen encouraged and helped me navigate the process of applying to grad school.”

Thanks to the skills he learned in Yeh’s lab, Leary is now pursuing a master’s degree in biostatistics at the University of Florida, even though the prospect of attending graduate school was never something he had considered before.

“I’ve worked with more senior people than me and people who know a lot more than me, yet they were willing to not just help me but also work as a team,” Yeh says. “Now, as an established professor, I want to pay it forward.”