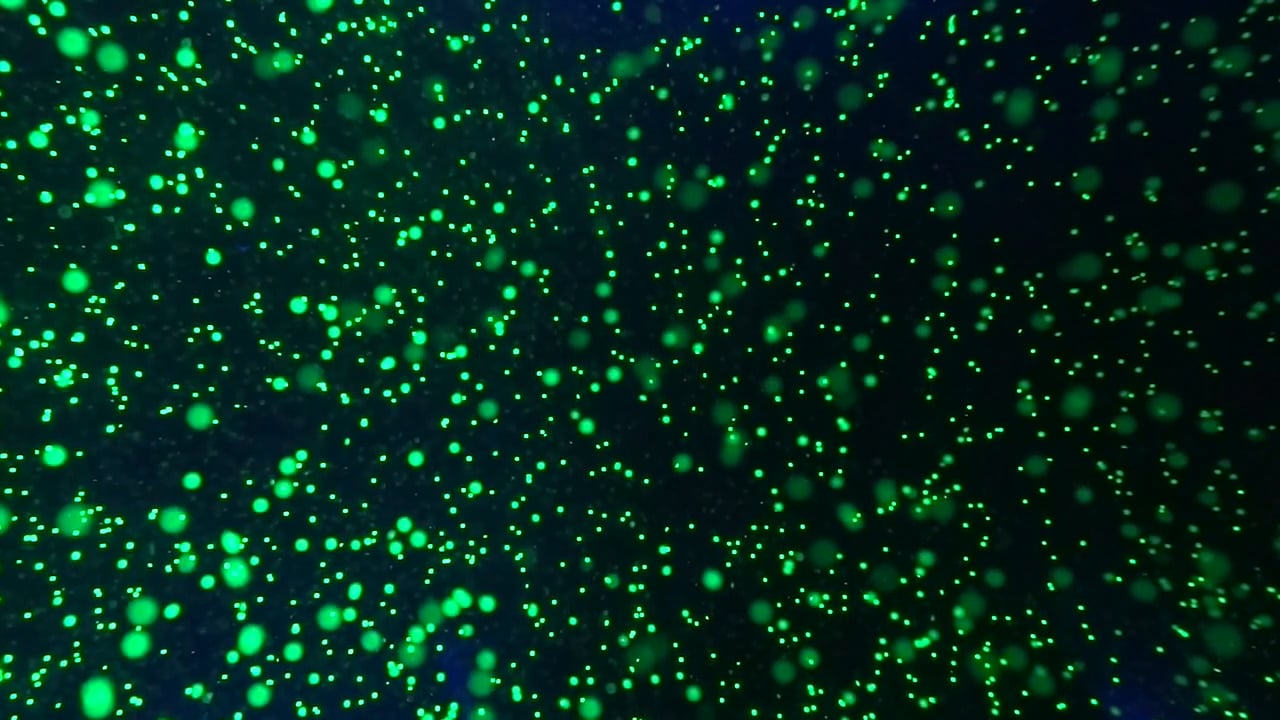

A four-foot tall glass tank filled with water and illuminated by a soft, emerald light sits in the back of a dark room at Morehead Planetarium. Thousands of tiny beads float in the water and glow with the same green light. A gentle wind-chime-like sound emanates from the tank. Suddenly, the beads begin to move, and the sound grows louder and faster. Then, slowly, they settle, the din now ambient and calm.

This is what you can expect from a viewing of “Granular Wall,” a sound installation created by Lee Weisert and Jonathan Kirk. A sound installation moves beyond pure sound — it’s 3-dimensional, visual, and musical, explains Weisert, a UNC-Chapel Hill music professor. The music comes from a generative process, rather than a composed score. In “Granular Wall,” that process is called fluid dynamics.

“The goal was to translate the ideas, complexities, and phenomena of fluid dynamics into music,” Weisert says. Although music composition using some scientific or mathematical law has been done before, “Granular Wall” makes the music as it happens, in real time.

Four propulsion jets inside the tank control the neutrally-buoyant “microspheres,” as Weisert calls them. Alternate timing of the jets creates fluid patterns for them to follow, and a motion-tracking program translates that movement into music. For example, as the spheres move higher in the water, the synthesizer plays higher pitches; and as they settle or speed up, the length of the notes gets longer or shorter.

“The compositional process was really about the sequence of the jets,” Weisert says. The different patterns the jets created are equivalent to the different movements within an orchestral piece — each pattern is a different movement.

The motion-tracking program presented one of the biggest challenges. Because the number of microspheres in the tank was so large, the program had issues processing the enormous amount of data. Plus, neither Weisert nor Kirk had any prior experience with motion-tracking technology. “We consulted a specialist on it. He basically said, ‘Good luck,’” Weisert says with a laugh.

Undeterred, Weisert and Kirk solved this issue by filtering out the dimmer pixels in the image, and then adding an image delay to the pixels as they moved. This left a trail of where they had been a few moments before. “The goal was not to 100-percent, perfectly represent the data, because that would create very uninteresting and very unintelligible music,” Weisert says. “The goal was to create a situation where, just by listening, you could discern what’s happening in the tank.”

Searching for sound

Weisert’s music has taken a number of forms, from pieces made exclusively from the sounds of shattering glass to more familiar combinations of electronic elements with orchestral instruments. Because of this variety, Weisert stands out from a more traditional composer who aims to perfect a unique sound. Instead, he constantly searches for new sounds and original ways to compose.

For example, “Shirt of Noise” keeps the listener curious to where the piece is going, but still retains a structure. “On the bad side, you could say that it’s not focused. On the good side, you have more unpredictability and a sense of discovery,” Weisert says.

That sense of discovery has led Weisert to take on a number of unique projects, including one titled “Cryoacoustic Orb,” in which the audience listens to the inside of a sphere of ice as it melts. Another piece, called “The Argus Project,” uses the changes in the environment around a pond to generate music.

“We’re trying to expose musical behaviors in environments that are outside our intuitive creative minds in direct and aesthetically interesting ways,” Weisert says. “The technology itself hopefully has a background role in the process.”

A new listening experience

The use of technology presents Weisert with a number of challenges to actually performing his pieces live. One of his newer works is a duo with saxophonist and fellow professor Matthew McClure that is entirely improvised. McClure plays saxophone while Weisert processes the music live, adding effects and modifying the sound as McClure plays. This high level of improvisation means that a traditional score will not work. Instead, they use shorthand notes on what type of sounds they want to convey in what order and improvise how they do that every time.

“That’s even becoming unnecessary,” Weisert says. “We’re becoming more familiar with what we can do and what each other’s contributions are.”

Weisert also hopes to have an effect on the audience, but in a different way from how music usually accomplishes this. His works don’t have a particular interpretation as a song may, but are instead focused on that sense of discovery. While he recognizes that people may derive meaning from his music, he wants to stay out of that and let the audience experience the music as he does.

“We’re trying to create in the listener the same aesthetic experience that we have as artists: discovering and searching for new music that didn’t exist before.”