North Carolina is one of the top ten agricultural-producing states in the country. But our state also ranks in the top ten for food insecurity, meaning that thousands of North Carolinians cannot afford to eat fresh, nutritious meals every day.

“It’s amazing to me that we have so many resources for local produce, but people with lower incomes are not able to access it,” says Lindsey Haynes-Maslow, a 2014 graduate of the UNC Gillings School of Global Public Health. Haynes-Maslow devoted her research to finding out why there is such a large gap between North Carolina’s produce and its people.

According to Haynes-Maslow, an individual or family can have the means to get food, but still be food insecure because the food they consume contains little to no nutritional value. “I look at food-security issues for people who lack access to affordable, healthy food,” she says. “It’s especially important with children. Healthy foods, such as fruits and vegetables, aid in child development and help children get the nutrients their bodies need.”

Growth spurts and physical development are only the beginning. According to Haynes-Maslow, studies show that nutritious eating greatly affects children’s behavior in school. “When they have a good diet, they have higher rates of attentiveness in school, they have less sick days, they’re more active, and they do better in school overall,” she says.

To get to the root of the nutrition problem in North Carolina, Haynes-Maslow conducted focus groups in six counties across the state, including Orange, Durham, Guilford, New Hanover, Onslow, and Buncombe. She spoke with over 100 people, primarily African American mothers receiving government assistance. Each focus group included six to ten people and all of the discussions revolved around access to fresh fruits and vegetables.

“The issue people talked about the most was cost,” Haynes-Maslow says. “The majority of the women said they simply could not afford fresh fruits and vegetables—especially when canned and frozen vegetables are cheaper and last longer.” With the reductions made in 2013 to Supplemental Nutrition Program benefits (formerly known as food stamps), Haynes-Maslow says most of the people she talked to have extremely limited food budgets that often can’t last through the month.

The second biggest problem the groups had was the low quality and availability of fresh produce. “Many women said they go to the produce section in their neighborhood grocery store only to find that the fruits and vegetables there are rotting, or they are poor quality,” Haynes-Maslow says. “A woman in Durham told me she had to go to a grocery store in an upper-class white neighborhood to get fruits and vegetables that look good enough to eat.”

As a researcher, Haynes-Maslow says this made her wonder about supply and demand. “There appears to be a demand from these lower-income groups. They say that they would love to buy fresh produce, but they’re not going to because their local grocery stores only sell low-quality fruits and vegetables,” she says. “Unfortunately, the message these grocery stores receive is that lower-income people do not want to buy fresh produce. They’re not going to stock it well because it doesn’t sell. It’s this circular, negative loop.”

Transportation was also a major issue for many of the women. “When we visited Asheville, we were in one of the city’s largest public housing communities, and the city had just changed the bus routes,” Haynes-Maslow says. “Before, folks from this public housing community could hop on the bus and go directly to the grocery store, but with the route change, they now have to wait almost an hour, so that greatly hinders their ability to go buy fruits and vegetables.”

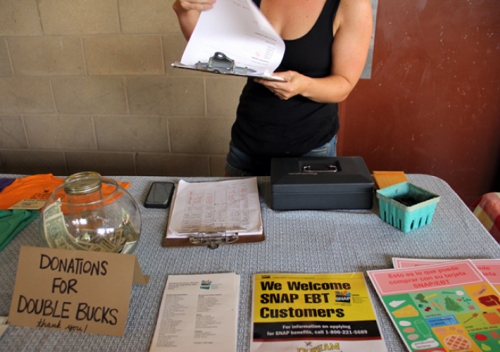

At the end of each focus group, Haynes-Maslow asked about different ideas people had for how to address these barriers. In 2012, the United States Department of Agriculture gave funding to the N.C. Division of Public Health to start mobile farmers’ markets, a concept similar to food trucks. Mobile farmers’ markets could bring fresh produce directly to low-income neighborhoods, work sites, or schools. But some participants in the focus groups had reservations about the idea.

“Safety was a concern, predominantly in Durham,” Haynes-Maslow says. “Some people were worried about the security of a mobile market because they usually do a lot of transactions in cash, and they didn’t want people to know there was a lot of cash on hand.”

The idea of community gardens was also discussed because it could eliminate three barriers at once: transportation, quality, and perishability. If a large garden were planted in a low-income neighborhood, residents could walk there, ensure the fruits and vegetables were good quality and well-maintained, and pick them fresh. But there were concerns about carrying out the idea.

“Who is going to sponsor it? Who is going to pay for all the supplies to get it started? One of the younger participants in the focus groups said she had no idea how to grow a tomato,” Haynes-Maslow says. “So education is a big issue.” And again, there were concerns about crime. “Some people who had participated in community gardens in the past said the gardens were occasionally vandalized or people would break in to them and take the food,” she says. “But in general, people like the idea of having direct access to fresh fruits and vegetables.”

While mobile food trucks and community gardens are both viable possibilities, Haynes-Maslow says some people expressed concern about not knowing how to cook with fresh produce. “With any of these initiatives, we have to include information on nutrition and preparation,” she says. “Cooking demonstrations, recipe cards, and nutrition information would be helpful.”

Her research shows that one program or initiative cannot provide a singular solution to these complex issues. Haynes-Maslow says we need several different programs working together to address all the barriers and create a food system that works for everyone. “We don’t currently have a healthy-food system that is accessible to everyone,” she says. “We have to do more work at the community level to help people make informed choices and to give them options.”