A 30-million-year-old crab claw sits on a shelf in a display case in Brian Coffey’s living room. Other ancient curiosities surround it: Pliocene whale vertebrae, a slab of polished alabaster from Egypt, a 100-pound amethyst geode from Brazil.

“I can’t help it. I like to look for stuff,” he says.

That’s an understatement.

As a kid, Coffey and his family would travel from Boone, North Carolina, to visit his aunt in Charleston, South Carolina, where they’d sift through piles of dirt dredged from the river at the local port. Bag upon bag they filled with colorful rocks and minerals, fossils, and shark teeth of varying sizes. Back in Boone, Coffey would quench his thirst for the search by exploring old quartz and mica mines, continually growing the family collection of treasures. Recently, his mother donated more than 1,000 pounds of their former finds to Appalachian State University for use as outreach materials for local schools.

Coffey’s love for the hunt continued as an undergraduate at UNC-Chapel Hill, where he majored in geology and worked in the archaeology research lab. For his senior honors thesis, he drove his red Subaru sedan all over Durham quarries and construction sites in search of paleosols — Triassic soils that developed before the Atlantic Ocean began to open 230 million years ago. As the earth’s tectonic plates began to pull apart, they created small rifts, one of which is in Durham. Studying these soils can reveal how the local climate changed over millions of years.

Years of digging through dirt can yield some interesting finds. Coffey has found large crystals, massive hunks of petrified wood, and fossils that are completely intact. One day at the North Carolina Botanical Garden, he discovered boxes of ammo that would lead police to a student who had shot and killed people on Rosemary Street in 1994.

And on September 11, 1994, his 21st birthday, he found an ankle bone of a Triassic predator never before discovered in North America.

Endeavors covered Coffey’s discovery in the Winter 2000 edition. While Coffey doesn’t work to uncover fossils anymore, he does create maps of what lies below the earth. And he’s looking for something that’s harder to find than you might think: energy.

But first dinosaurs

Raw-ih-soo-kee-un. That’s how you pronounce rauisuchian, the species of dinosaur whose ankle bone Coffey found nearly three decades ago. The Monday after he stumbled upon it, he brought it to the office of UNC geologist Joseph Carter, a paleontologist who has spent most of his career studying prehistoric mollusks like clams. Carter knew immediately it was a dinosaur bone and that he needed to get over to the active quarry where it was found to recover the rest of its body.

With help from numerous students, Carter spent the next decade piecing together the fossil and the three found around it. Inside the rauisuchian’s stomach was an armadillo-like reptile and a feline animal. Alongside it was what geologists believe to be its opponent: a rare, crocodile-like predator called a sphenosuchian.

UNC geologist Joe Carter spent nearly 20 years piecing together Alison the Rauisuchian, which he presented to the public at Memorial Hall in 2013. (photo by Donn Young)

Coffey, on the other hand, only had the opportunity to work on the rauisuchian — often described as a mix between a bear and a crocodile — during his last year at Carolina. At that time, he visited Carter’s lab often, cleaning up pieces and gluing them together.

“It was a one-off kind of project,” Coffey says. “And it was fun to track it throughout the years as I went to graduate school and studied other things.”

Coffey headed just a few hours north to Virginia Tech. He continued to study sediments deep in the earth from the early Cenozoic Era, about 35 million years ago, along the Carolina Coastal Plain. Just like he did with the bones of the rauisuchian, he’d collect pieces of data to stitch together a story of the subsurface — a process he still performs today.

The path to energy

Coffey continues to make maps of the planet’s innards as a senior staff geologist at Apache Corporation, an energy company headquartered in Houston. He began working in the oil and gas industry in the late 1990s after graduating with his PhD from Virginia Tech. His first job was at Exxon Mobil. While he enjoyed his time in academia, he saw the abundance of opportunities the energy sector offered: project diversity, collaboration, and travel — lots of it.

Coffey has visited more than a dozen countries for work, including Brazil, Saudi Arabia, Australia, and Egypt. He’s also traveled all over the United States and Canada.

“The best geologists are the ones who’ve seen the most rocks,” he says with a laugh. “We have this mental database in our heads.”

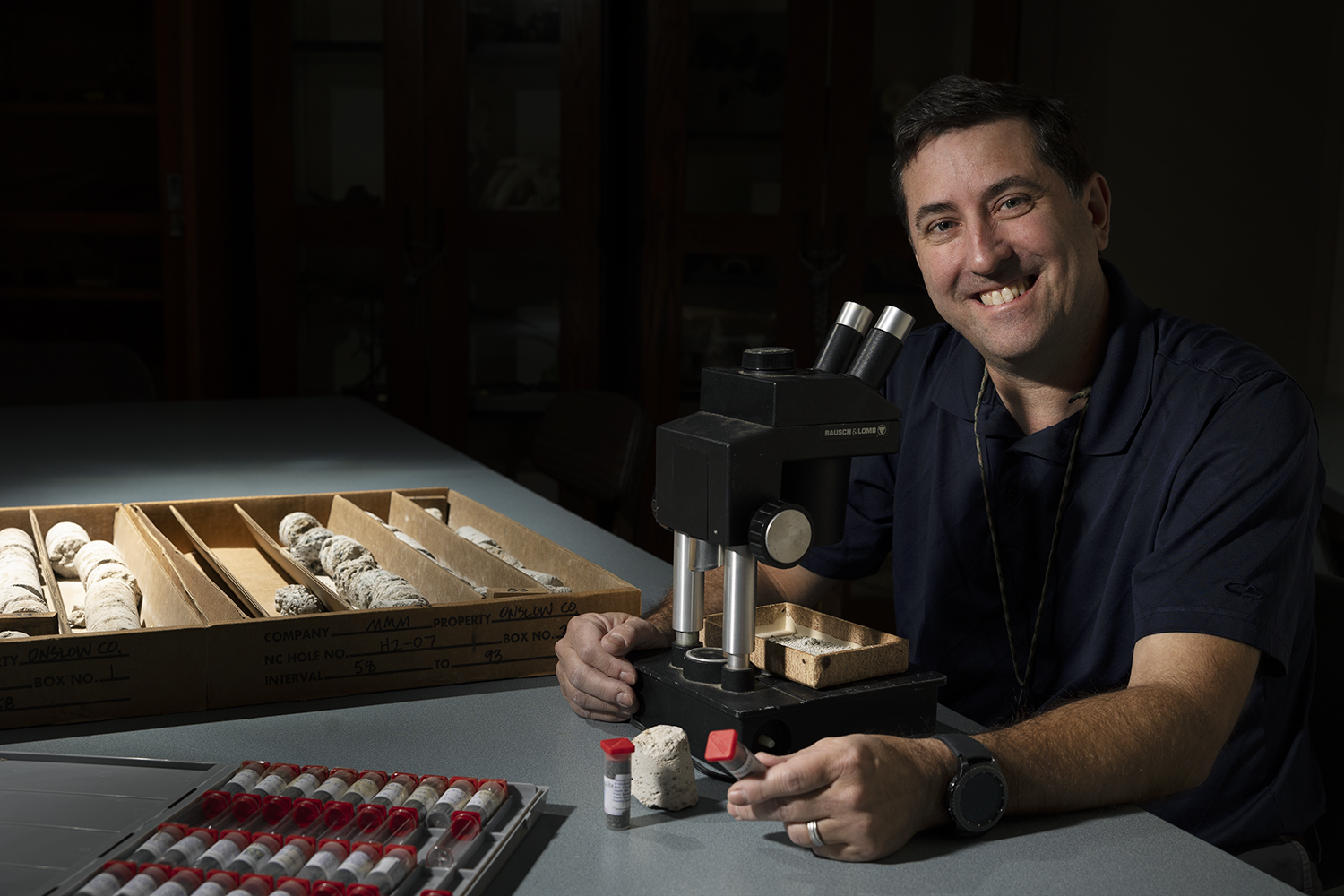

Geologists like Coffey analyze cores of earth taken from potential extraction sites to determine the type and amount of resources that exist there, the process needed for extraction, and safety measures that should be taken. When physical samples can’t be acquired — which is often the case — they send signals into the ground and record the pulses that bounce back with microphones. The information this unveils is called seismic data.

Coffey explores a potential extraction site in the Guadalupe Mountains of West Texas. (photo courtesy of Brian Coffey)

“Most of the time, you’re collecting remotely measured data,” he says. “You drill a hole, drop a tool down it on a cable, and measure the physical properties as you pull it back up. It’s called a wireline log, and it’s fascinating what they can do. We need rocks to calibrate these geophysical responses — that’s where I come in.”

This work is not only used to identify new drill sites but to optimize existing ones. Doing the latter means less drilling elsewhere, Coffey says. When he views physical samples under a microscope, he looks at grain type, size, shape, and composition. Grains with holes mean hydrocarbons are likely stored in them. The presence of cements or clays suggest that extraction might be difficult. Fossils inform sediment age and environment.

“Sedimentary geologists often think of the world as a deck of cards that are splayed out, each card having potential to be a different, discrete package of rocks that may or may not connect laterally with the next card,” Coffey says. “And my job is to reduce those uncertainties. Predicting what we must go through before we get to our target is part of the game. In this world, a little mistake can cost lives and millions of dollars. So there is great care in trying to mediate that.”

A return to Carolina

While Coffey has lived in numerous locations and traveled all over the world, Carolina has remained a central part of his life. It’s where he met his wife, a fellow geology graduate, and where he returned to in 2007 as an adjunct professor. While he works remotely for Apache Corporation today, he lives in Chapel Hill with his wife, who works in RTP, and his daughter, a first-year student at UNC. She’s considering a major in geoscience.

While the geology department has changed dramatically — it’s now located in the Department of Earth, Marine, and Environmental Science — his daughter’s consideration of the subject excites him and urges him to reflect on his own fond memories of the department.

“The geology department was a very special department,” Coffey remembers. “It was very embracing. It was like a family, one I’ve stayed in touch with.”

He recalls the professors who made an impact on him: John Dennison, Daniel Textoris, Geoff Feiss, Allen Glazner, and Kevin Stewart, who is still a professor on campus.

What Coffey has always appreciated about the field of geology is that it mixes disciplines, like physics, math, and biology — and it forces you to think critically.

“The professors I had at UNC really emphasized thinking,” he says. “There’s never just one answer. It’s not a formula. It’s a creative process. And for that I’m lucky. I’m in a role where I get to think.”