A 6-year-old girl in Campinas, Brazil is addicted to crack. A destitute mother in Kabul, Afghanistan feeds her children opium.

Welcome to the side of drug addiction we don’t hear about, and almost never see. This is where UNC psychologist Hendreé Jones works every day.

—

In a small village in Afghanistan, a man forces his wife to weave carpets for 18 hours a day. Her hands become rigid and unbearably sore from the repetitive motion and constant overuse. Her husband gives her opium—it relieves her pain, but it also keeps her under his control. She slips into a relaxed, semi-lucid state. To calm her rambunctious young children, she gives them opium as well.

“She was forced to weave carpets, and be a drug user, and take care of her children, and take care of the entire home in terms of food, water—everything,” Jones, a UNC psychologist and drug addiction expert, explains.

For women in Afghanistan, these circumstances are not unique. When each day presents harsh challenges, using opiates can make the burden seem a little less heavy.

How do you help an entire family addicted to opium?

That’s the question the U.S. Department of State posed to Jones in 2009. Then they asked, “would you be willing to go to Afghanistan?”

“Yes,” she said. “I’d love to go.”

“Drugs go against God”

Since the early ‘90s, Afghanistan has been the world’s leading producer of opium, with the country’s poppy – the main ingredient in heroin – fueling 90 percent of the world’s heroin supply. While this has been the case for the better part of three decades, addiction among Afghan people has skyrocketed during the past 15 years of war. Reports show that people of all ages struggle with opium addiction. Some children are born addicted to it from prenatal exposure.

“Afghanistan has the reputation of being the hardest place in the world to be a child,” Jones says. “I wanted to see that, and see what we could do.”

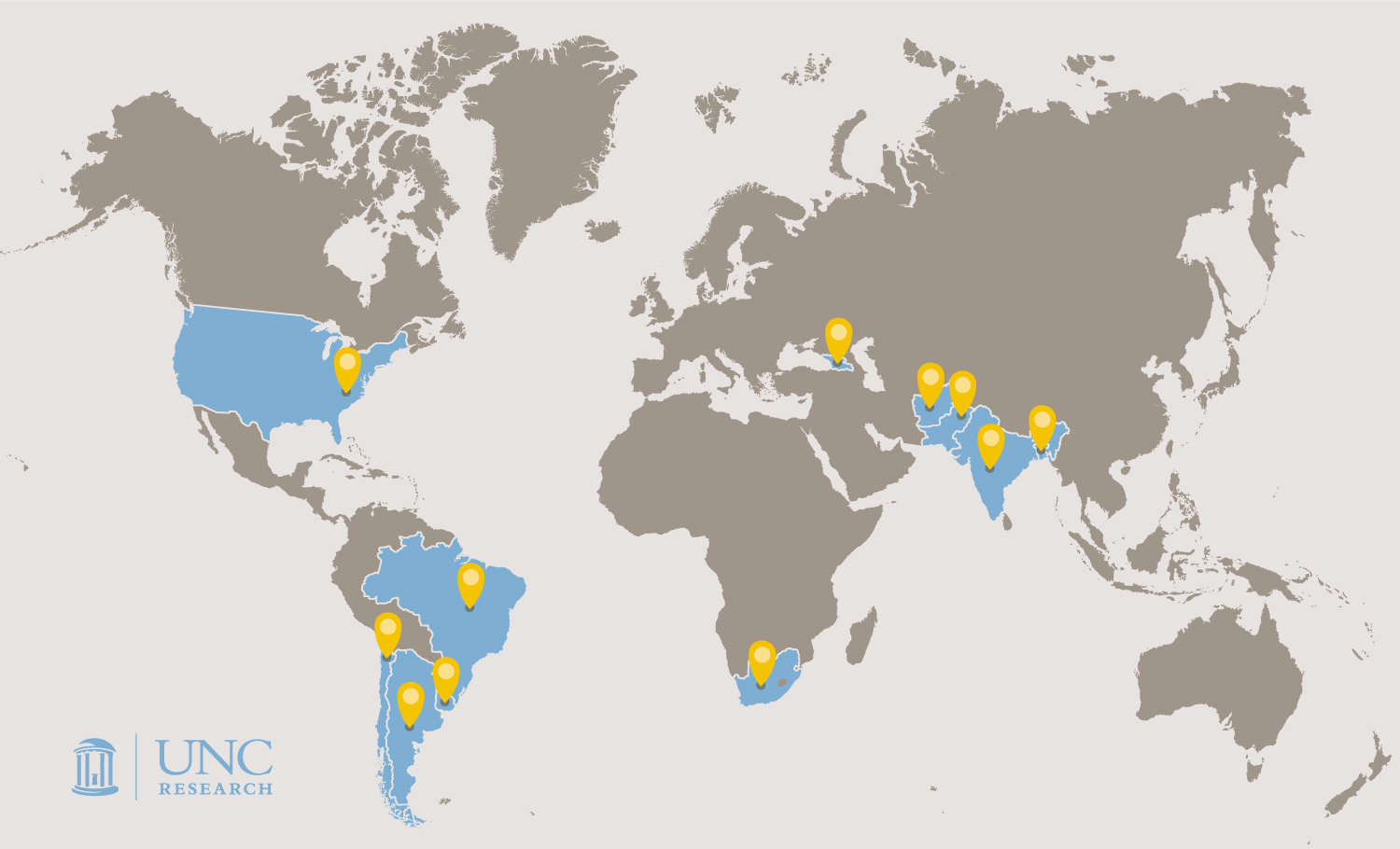

In the wake of an oppressive regime and fifteen years of continuous war, many people living in Afghanistan have turned to opium for relief from their suffering. In the continuing effort to stabilize the country, the state department started building centers to treat opioid addiction in the late 2000s. With her renown expertise in prenatal drug exposure, neonatal abstinence syndrome and maternal treatment research, officials from the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs (INL) reached out to Jones, and asked her to tour these centers (over 30 of them spread all across the country) and identify methods for making them more effective.

In this culture, drug addiction treatment often boils down to convincing the man of the household that he and his family should seek treatment. One of the biggest challenges is getting women into the treatment facility in the first place. “A male partner or relative has to agree and has to sign for them to come in,” Jones says. It sounds unlikely, but it does happen. Jones helped convince the husband of the woman who was forced to weave carpets for 18 hours a day.

The state department worked with the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime to ensure resources and capacity for whole families to go into treatment at the same time. Still, the new treatment centers weren’t producing the desired results.

The people working at these centers needed support and counseling tools, according to Jones. The standard counseling intervention advocated the idea that doing drugs is against God.

“That wasn’t particularly effective,” Jones says. “We wanted to give them more.”

Wait out the withdrawal

For a person on opioids everything slows down. “Your eyes won’t water, your nose will become stuffy, your digestive track becomes sluggish,” Jones explains. “Then, in the absence of that drug, the withdrawal produces the opposite effect—everything rushes out.”

People experiencing withdrawal from opioids suffer from flu-like symptoms—runny nose, sweating, fever, and diarrhea. In Afghanistan, medications like methadone are illegal. “The only thing a physician in Afghanistan can do to address withdrawal is to treat the symptoms,” Jones says. “A doctor can prescribe anti-diarrhea medicines or Benadryl to help with the anxiety and restlessness, but they can’t give the actual medication that would be most helpful.”

It typically takes eight days for a person to go through withdrawal. “We agreed in our protocol that we wouldn’t do much psychological or social work during that time because the patient is not going to remember it or absorb it,” Jones says. “We allow them to go through that withdrawal process before we start the intervention.”

Once their minds are clear, the education, therapy, and support can begin.

Empower through education

Many women and children in Afghanistan are addicted to drugs because their circumstances are so dire—they suffer immense physical, sexual, and emotional abuse. Oftentimes they aren’t allowed to leave the house. “They’re not allowed to work. They’re not allowed to go outside,” Jones says. Only 17 percent of women in Afghanistan can read. “If they don’t know how to read, they’re not going to transmit that knowledge to their children.”

In addition to addressing trauma and addiction, Jones wanted to make sure the women and children in these centers had access to learning other skills—like making art— that would not only give them a better chance at drug abstinence, but might also a give them a better chance at living a more fulfilling life.

“When women and children can’t read or write they need other ways of expressing themselves,” Jones says. “So using art therapy techniques was a really nice way to engage.”

A child at the treatment center in Kabul, Afghanistan drew this sketch to illustrate what he wants his future to look like.

The comprehensive protocol Jones developed covered everything from basic drug refusal skills, to lessons in reading and basic arithmetic, to sexual assault prevention. “We looked at how to develop practices to talk about sexual abuse, and how to stop sexual abuse,” Jones says. “And how to communicate those things in a culturally sensitive way—but also stand up for yourself.”

With support from the state department, the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime organized trainings so that the local Afghan staff at the centers could learn all the new protocols. As they trained local people, Jones made sure research happened simultaneously. In collaboration with UNODC, she and her team developed a database with over 700 children that were followed throughout the treatment. So far, Jones says the data show sustained improvements for children suffering with mental health issues such as depression and violence and loss.

As for the woman forced to weave carpets, she and her children came into the facility in Kabul, Afghanistan to receive treatment. She completed the 90-day treatment during which she learned to read and acquired basic numeracy.

After the three months are up, outreach workers go visit the woman in her home on a regular basis for another 12 weeks to reinforce the tools and skills the women and children learned.

Support the staff

Doing this kind of work is not easy. Doing it every single day is often overwhelming — especially for people who live in a war zone. So the staff training and protocol includes a large self-care component. “That is actually a really new concept for some of them,” Jones says. “Treating trauma can bring up a lot of the staff’s own traumatic experiences that have been suppressed and shut down.”

Afghanistan is not the type of place where people openly discuss their feelings. Jones and her team have to find ways to work with and heal the staff. The training offers tools to help the staff begin the process of healing so that they can develop a larger capacity to help others. “You have to heal yourself before you can heal someone else,” she says. “That’s been a huge challenge.”

Pack a big suitcase

Approximately 8,456 miles away, Jones is deep in conversation on a dirt street in Campinas, Brazil. The lights, powered by illegal electricity, flicker on and off. Out of the corner of her eye, she watches small children run through the street, zigzagging between enormous piles of trash. Jones turns back to the conversation – she and her translator are talking to one of the local drug dealers.

Impressed with the success of her work in Afghanistan, the state department sent Jones to another place with a serious drug problem.

But the situation in Brazil is very different from Afghanistan.

Poor communities like this one are governed by drug dealers who will often approach 5-year-old children, and ask them to put something in their pocket in exchange for some candy. Children can’t be arrested. “If police catch minors, they may shake the child down for the drugs and their money,” Jones says. “And if you’re a girl, they may shake you down for sex too,” Jones says. “And sometimes if you’re a boy.”

So children start running drugs, and they’re paid in a little bit of money or candy, and eventually they’re paid in crack. Then the dealer has a ready customer as well as a worker. They also employ children as look-out people. They have guns—almost on the order of child soldiers, according to Jones. The children are paid to make sure nobody is coming while a drug deal is happening, or if someone is, they send an alert or shoot.

After assessing the community and existing infrastructure (there was a drug treatment facility) “we knew no one was going to let their kid come in for treatment,” Jones says. If the kids couldn’t come to her, she would go to them. Jones wanted to get a mobile unit.

Mobilize treatment

It sounds simple enough, but you can’t just roll up into a neighborhood run by drug dealers without explaining yourself. “For anything to be sustainable, it has to be rooted in the community. They wanted to know who we were and what we were doing,” Jones says. “They run the place. They give shelter and protection and food and drugs and everything. You have to be careful.”

Jones wanted to get a van, and outfit it with a nurse, an educator, a psychologist—a mobile unit that could go around to different favelas and offer basic healthcare and therapy. She also had staff to act as entertainers to attract and establish rapport with the children in the community

But she knew she had to slowly and respectfully engage the community. In her talks with the community stakeholders, she and the team stressed this message: “We want your community to be healthy. We want your children to have a childhood.

“And they didn’t disagree with that,” she says.

Her approach worked. “Our team members weren’t seen as adversarial. We made sure that we were transparent with everyone in the community. We talked to the police and asked them for their help to be a distant but stable presence. Distance is needed from the van and the team as the police are often seen as adversaries.”

A truck and trailer were converted into a mobile clinic of sorts. The team, with Jones on board, could drive it into the favela, unhook it, and then if there was a child who needed medical attention, or a social service appointment, the children could be driven out of there in the truck, while the rest of the team stayed and did their work.

It went out every week, rotating between three different communities. “There was a routine and timing to it,” Jones says. “We never went too early in the morning, or too late at night. We were always out of there by dark.”

One young girl who visited the trailer was a 9-year-old addicted to crack. She explained that her drug use started when her father gave her the drug “to make her feel better” and quickly progressed from there. “Our psychologist worked with her, and eventually learned that she was being sexually abused and steps were taken to help keep her safe and help address her trauma,” Jones says. “Later follow up reported that she was not using crack and living with another family member.” We helped her to get back into regular school attendance and be more integrated into the community, in a better, healthier way.”

Reach the rest of the world

After Brazil, the State Department once again requested Jones’s expertise—this time they wanted her to create a global protocol. “What we did in Afghanistan and Brazil were different,” she says. “The principles and exercises are similar, but there are also big differences and it’s really important for each community to adopt it and make it their own.”

Jones developed a more generic version of the trainings she had done in Afghanistan and Brazil, with instructions about recognizing cultural differences and community differences. It covers things like basic counseling skills for children and how to address their trauma.

Of the volumes of materials she has created, Jones’s favorite is the Suitcase for Life—she describes it as the nuts and bolts of the intervention work done in Brazil and Afghanistan. “The idea is we’re giving them a suitcase of skills that no one can ever take away from them.” The suitcase includes eight modules: artistic expression, communicating and relating, dealing with stress, understanding the harms of substances, keeping the mind and body healthy, keeping yourself and others safe, being a good citizen, and then dreaming and planning for the future.

Jones plans to go back to South America to do more trainings, and to eventually conduct a randomized controlled trial on the protocols. “We want to know with certainty that it works, or that it’s better than customary care,” she says. “We want to professionalize substance use disorder treatment for children.”

Because the vast majority of substance use disorder programs cater to adults, Jones is working in unchartered territory. “These are young children—ages six, seven, or eight—who have learned how to survive on the streets,” she says. Their street smarts help them survive, but they don’t listen well, and they have trouble connecting. It can be exceedingly difficult to develop a relationship with them. “It can be a huge challenge to get a child to listen to you, to pay attention to you, to respect you – to establish a boundary of any kind,” Jones says. But the struggle is worth it. Throughout all of her work, from developing modules to implementing trainings, Jones focuses on helping these children have a childhood—that means time to play, time to sleep, time to eat, and time to dream.

“I don’t care what language you speak—dreaming about the future is a universal concept. If you don’t have hope for the future, you’re never, ever going to change anything.”