Alexander the Great never lost a battle. He was taught by Aristotle. He founded more than 70 cities and was called “Son of Zeus.” He consistently ranks among history’s most influential people and, in stories, he knew how to fly.

In many regards, Alexander seems larger than life. His accomplishments from 336 to 323 B.C. are well-studied and his armies’ victories on the battlefield have been lauded through the ages. But until Fred Naiden, a history professor at UNC, started examining the role religion played in Alexander’s sweep across the Middle East and Asia, little was known about factors other than military strength that contributed to his swift ascendancy.

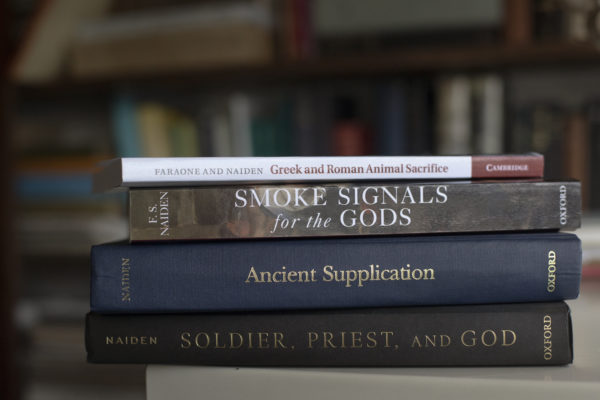

Naiden’s previous books cover different traditions in ancient Greek and Roman culture including animal sacrifice and the social practice of supplication. His most recent book, “Soldier, Priest, and God,” is his first on Alexander the Great. I photo by Megan May

What Naiden found was a wealth of information and a new perspective on how Alexander used regional religions to his advantage.

“Not only was he good at conquering people, he was good at avoiding conquering people when he could convince them to accept him as their ruler by sharing their religion,” Naiden says. “In effect, by becoming one of them.”

Naiden has spent the last 10 years studying how Alexander harnessed local beliefs to secure power. In December, he published the first religious biography of Alexander the Great, “Soldier, Priest, and God.”

Lessons from the successes and failures of Alexander’s conquests ring across the millennia. From the rise of the Taliban to Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation, religion and power are deeply intertwined. Examining how one of history’s greatest conquerors used belief systems for political legitimacy is something that leaders can still learn from, especially in a time when the world prickles with religious strife.

Seeing the other side

Although power and religion go hand in hand today, the relationship was much more direct in the past. Religious leaders were also political leaders: priests were governing officials and Egyptian pharaohs were hailed as gods.

“The ancient world is not a democracy in which people govern themselves. The ancient world is a sort of oligarchy in which the gods are supposed to govern the people,” Naiden says.

In his book, he lays out how Alexander succeeded when he wielded religion successfully and failed when he didn’t. In places Alexander triumphed — Babylon, Egypt, Tyre, and Greece — he made sure to have the priests on his side and submit to the local religious ceremonies conferring leadership. In doing so, he took on the role of someone the region’s gods had bestowed power to, rather than that of a foreign conqueror.

At the beginning of Alexander’s campaign, his home kingdom of Macedon was small. Although he fought in many bloody battles and is renowned as an exceptionally clever strategist, even Alexander couldn’t strong-arm millions of people into accepting his authority. So he tapped into another avenue of power — the idea of the divine right to rule.

“Religion dominated warfare because gods dominated everything,” Naiden writes in his book. “All ancient commanders played religious parts, but Alexander played the most. He uttered or inspired the most prayers and made the most sacrifices, and he did so in the most places, languages, and rituals. We may think of him as the Pope, the Holy Roman Emperor, and the head of the Church of England, all in one.”

This side of Alexander’s story is relatively unexplored, Naiden says, because the majority of scholars who study him have backgrounds in ancient Greek and examine texts written in Greek or Latin. These accounts, written by ancient historians, place an emphasis on Alexander’s military exploits. But Eastern writers, on the other hand, thoroughly documented their leaders’ spiritual importance and the sacred duties that they carried out. In these records, Alexander isn’t depicted as just a warrior, but as a religious figure who performed ceremonies, prayers, and sacrifices. He is also one of the few people directly quoted in the Quran, according to scholars.

“It is the Near Eastern sources that see the other side,” Naiden says.

Like Alexander, Naiden has forged his own way into the unknown and proven himself a master in his field. But while Alexander was set on his path at 20 years old, it wasn’t until Naiden was in his late 30s that he found the one he’s on now.

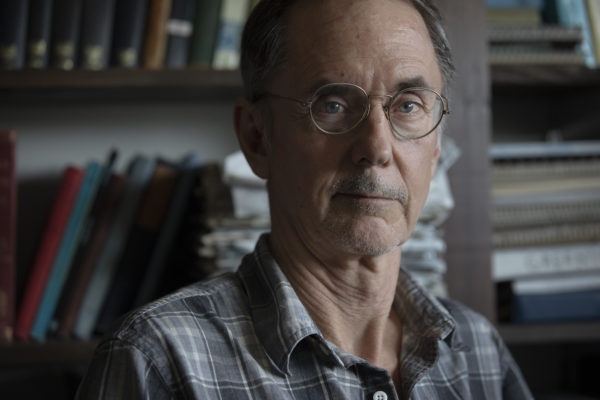

Fred Naiden worked as a locomotive engineer in New York City before getting involved in academia in his mid-30s. Now a history professor at UNC, he studies how Alexander the Great used religion to rule. I photo by Megan May

Ruling new lands

Before he forged his way into academia, Naiden drove subway cars and later operated small freight trains as a locomotive engineer in New York City. He worked long enough to secure a modest pension and, partly because of his bad back, decided to quit his job.

“I knew Latin as a boy and it struck my fancy to try to learn Greek,” Naiden says. “A friend of mine who was a taxi driver said, ‘That’s what you should do in your spare time now that you’ve quit, before you get another job.’ So I learned Greek.”

He excelled. The teachers at his night school — professors at the City University of New York — told him to apply to the college’s graduate program for Greek language. Naiden was accepted and graduated in 1995.

He continued learning ancient history and languages and eventually earned a PhD from Harvard in classical philology — the study of ancient texts and records — in 2000. He began teaching at Carolina in 2007.

During his studies, Naiden learned languages that would give him an edge when studying Alexander. Besides Latin and Greek, he is well-versed in Hebrew and Akkadian, the language of the ancient Babylonians.

“I learned as much of the Near Eastern languages as I could. I studied the most important of these languages, Akkadian, at Harvard,” Naiden says. “It’s somewhat similar to modern Semitic languages, especially Arabic, but it’s a long-dead language. When Alexander arrived, it was still used for literary records and for ceremonies.”

Babylon, in modern-day Iraq, was regarded by the ancient Greeks as the largest, richest city in the world. Judging from surviving records, its leaders also had a knack for bureaucracy, and museums around the world are full of Babylonian letters, accounts of ceremonies, and bills of sale written in Akkadian. These records may be valuable to researchers, but to the untrained eye the language more closely resembles chicken scratch than a glimpse into the past.

Through his linguistic knowledge, tenacious investigation, and deductive skills, Naiden uncovered what Babylon was like when Alexander’s army arrived in the city. By combining archaeological findings with ancient records, he described the beautiful but aging buildings, the deals Alexander and the Babylonian priests made, and the parade that led the conqueror and his army toward Esangil, the temple of the chief god Marduk.

A granite statue in Frankfurt’s Liebieghaus depicts Alexander the Great as pharaoh. I photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

“I was the first person to do this — and that surprised me,” Naiden says. “But this is because of the bias. There’s too much emphasis on Western sources, too much emphasis on derring-do, too much military history and not enough other history.”

Ruled by the Persian Empire, Babylon was not permitted a king because of its frequent rebellions. But Alexander had overthrown the Persians, and now the city was hungry for a new leader. Naiden found that in exchange for the city’s kingship, Alexander agreed to protect Babylon and follow a number of important religious ceremonies and rituals.

Alexander experienced a similar rise to power in Egypt. Learning about his reign along the Nile was particularly exciting for Naiden, especially after a game-changing text was found in the basement of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo 10 years ago. The document, which described how Alexander became pharaoh, helped Naiden understand that the Egyptians held him in high regard. Along with other titles, he was declared “Alksandros: Ruler of Rulers of the Entire Land,” and the divine son of the god Amon.

Naiden’s research also considered what Alexander’s men thought of their leader’s immersion in foreign beliefs. “They thought this was nonsense,” he says. “On the other hand, they didn’t tell him to stop being pharaoh. There was an obvious practical advantage to do it the Egyptians’ way.”

Finding what’s lost

Naiden’s research led him to Europe, Anatolia, Syria, and Greece, but most of his analysis relied on the enormous collection of documents shared by universities across the world through interlibrary loans.

With these records and expert translators, he was able to parse out the religious nuances of Alexander’s success. And, in other cases, uncover how a lack of spiritual mastery led to failures.

The further Alexander traveled east, the more unfamiliar the religions he encountered became. He fumbled badly in India because the belief systems there were difficult for him to understand. To the west, many faiths had an emphasis on animal sacrifices, whereas India did not, and he found the emerging religions of Buddhism and Jainism baffling.

“He attacked the religious leaders of the people,” Naiden says. “In India, he slaughtered many, and I take the lack of religious contact and the resort to violence to be interdependent phenomena.”

It was India that marked the end of Alexander’s expansion east. The fighting there was brutal, and many of his soldiers were tired of campaigning and wanted to turn back. He agreed and returned to Babylon to rule his empire.

Even if Alexander managed to embrace India’s faiths, Naiden says that he isn’t sure what it would have taken for Alexander to become ruler.

“For that, we need written records from India, from this general period if not this specific time, showing what a successful king did. And we don’t have those,” Naiden says. “We have some evidence, but we don’t have anything like the Babylonian and Egyptian royal scripts for proper conduct that I was able to use for this book. I looked hard for the Indian equivalent — and I couldn’t find it.”

Alexander’s conquests in India are infrequently studied partially because there simply isn’t a lot there. The region’s humid weather and thick forests aren’t kind to ancient artifacts.

“The jungle swallows sites up in a different way than the desert does,” he says. “The desert swallows and sometimes preserves. The jungle swallows, but is less likely to preserve.”

One particularly important place that has been swallowed up by time is Alexander’s tomb. He died in 323 B.C. in Babylon at the age of 32, and it is believed that the last time he rose from his bed was to perform a sacrifice to the gods. The location of his tomb has remained a mystery for over 2,000 years, but an archaeologist’s recent discoveries in the ancient royal quarters of Alexandria, Egypt, may finally lead to an answer.

Burials in Alexander’s time were oftentimes political tributes, as they sometimes are today. If the tomb is found, and the sarcophagus is intact, Naiden says that the discovery could reveal how Alexander’s religious importance in Egypt, Greece, and other lands he ruled was incorporated into his funeral rites and burial.

But what did Alexander himself believe? While he worshipped the gods of his Greek homeland, Naiden says that he added aspects of the religions he experienced into a spiritual stew all his own.

“This is something that had never been attempted before. He believed in the unity of the heavens, through his own, unique religious position. He was a polytheistic Jesus with a siege train.”