For most kids, the end of August means the end of summer. Trading in tank tops, swimsuits, and sunshine for back-to-school clothes, a new pack of pencils, and the fluorescent glow of a cylinder block classroom. It’s a sad return to normalcy, schedules, alarm clocks, and responsibility. But for more than 900,000 economically disadvantaged North Carolina students, it means not having to wonder where their next meal will come from.

North Carolina has the 10th highest rate of food insecurity in the nation, meaning that many households in the state have difficulty providing enough food for all their members. Families with children, and especially those headed by a single parent, are among the most impacted demographics. The COVID-19 pandemic has only worsened these numbers, further limiting access to resources and forcing some families to choose between eating a meal and paying for rent and other essentials.

What’s more, 40% of food produced in the United States is wasted every year. These statistics motivated three sophomores at Enloe Magnet High School in Raleigh to create an application that helps minimize food waste at food pantries and food banks.

This past year, Siddharth Maruvada, Arnav Meduri, and Abhinav Meduri won the regional and state rounds of eCybermission, a web-based STEM competition for sixth through ninth graders. They not only placed first at nationals in the ninth-grade category, but they also received a grant from the Army Educational Outreach Program to continue implementing the app — called Pantry Patrol — in their community.

“But there was a lot of learning involved,” Arnav says, with a laugh.

The trio wanted to keep addressing hunger — and do it in a big way — but needed more guidance.

“We wanted to really do something that could help the community and lend a hand in any way that we could during these difficult times,” Maruvada says. “That was our main driver.”

A brief internet search led them to Alice Ammerman, a nutrition and public health expert and director of the UNC Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. Her research interests in food insecurity, they thought, aligned perfectly with theirs. Soon after emailing Ammerman, they received a reply: a list of reading materials to help them learn about the challenges surrounding food waste.

“There’s a huge disconnect between people needing food and food being thrown away,” Ammerman says.

Abhinav Meduri (right) and other volunteers help sort potatoes in the hot warehouse of the food bank. In three hours, they packaged 14,541 pounds of potatoes, which will provide more than 12,000 meals to food bank beneficiaries. (photo by Elise Mahon)

Ammerman recognized the potential of such a project and decided to take a step further, providing more than just literature and expertise on the subject. Thanks to her involvement with the North Carolina Local Food Council, she connected the students with two employees from the Food Bank of Central & Eastern North Carolina: Gideon Adams, the vice president of community health and engagement, and Angie Nesius, the data and record collection coordinator at the Raleigh branch.

“[The students’] real power for me was how they would interpret human impact and that practical nuance into data,” Adams says. “I felt really comfortable sharing what I had seen and experienced working in the field and immediately felt that they would not only get it but be able to translate it.”

Focusing on food waste

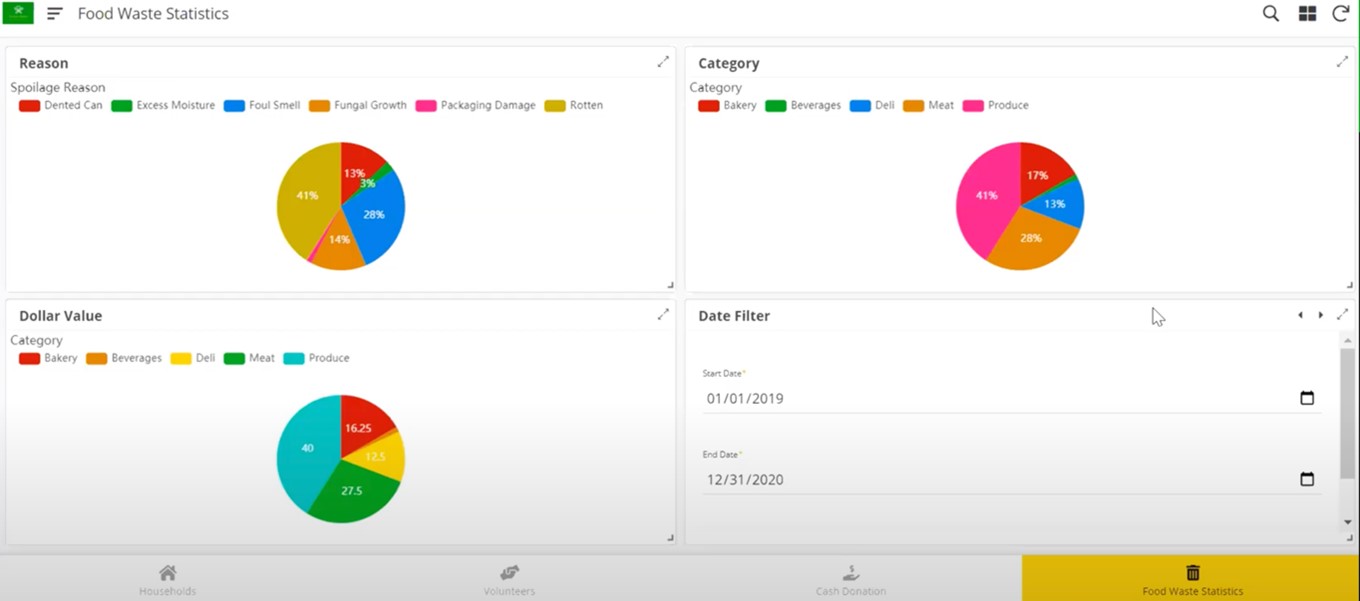

Working closely with Adams and Nesius enabled the team to tailor the Pantry Patrol app to best fit the food pantries’ needs. They focused on food waste and developed new features like food waste dashboards, food inspection trackers, and customizable data visualizations that allow the food pantries to determine when and how food waste is occurring in their systems.

“Depending on the start and end dates you set, the graphs will automatically populate with those different values,” Abhinav explains. “You can see food waste by category, spoilage reason, and dollar value.”

Inefficient food labeling systems and overly cautious expiration dating are factors that exacerbate food waste. The expiration dates printed on most food products, according to Ammerman, are chosen to reflect peak taste and promote sales rather than basing them on safety and when the food will actually spoil. In response, many food banks and pantries have adopted a system for calculating a reasonable date beyond the “sell by” or “use by” dates — otherwise, they were throwing away a lot of food that was safe and nutritious.

A screenshot of the Pantry Patrol app depicts food waste statistics in the form of pie charts. This tool allows the food bank to visualize waste by identifying the type of food being wasted, the reason why, and the dollar equivalency of the waste.

The Pantry Patrol team saw this as a perfect opportunity to minimize waste and integrated these extended expiration dates into their app. They soon realized that helping the pantries transition away from pencil-and-paper methods of record-keeping could improve their efficiency, too. They began adding new capabilities to log clients’ food sensitivities, preferences, and allergies; track volunteer hours; and manage a variety of other food pantry needs.

“There are just so many different ways that this can impact our network,” Nesius says. “For example, we often receive grants to fund freezers and refrigerators that we can pass on to our partners. If we find that some foods are being thrown out because the pantry does not have the ability to freeze excess perishables, then this might be a way for us to identify which partner agencies we should target with the freezers funded through grants.”

The app is currently being used by two North Carolina food pantries in Spring Hope and Roxboro, North Carolina. The team hopes to roll out the application to about 15 food pantries by the end of the year.

This collaboration between Ammerman, the Pantry Patrol app developers, and their food bank partners empowers youth to enact real change in their community through engagement with experts and research.

“These kids are going to, hopefully, inspire others,” Adams says. “The fact that we have such a close connection with Alice and with UNC shows how beneficial those relationships are, and if they’re beneficial for us they’ll be beneficial for other people as well.”