People mill about the Pleasants Family Assembly Room in Wilson Special Collections Library, leaning over tables covered in artifacts from the Civil Rights Movement. One woman pauses and picks up a photo of a young African-American boy demonstrating for equality in front of a courthouse in Selma, Alabama, in 1964. She is startled to realize the image depicts deputies approaching the young boy, revealing his impending arrest.

Suddenly, Christie Norris draws everyone’s attention to the front of the room. “Select three artifacts that reflect what you most want students to understand about the Civil Rights Movement,” she says. The teachers split into groups to discuss their choices and narrow down their selections.

“Teachers always come away from this activity with a more critical eye regarding which narratives we advance, contest, or accept as ‘true,’” Norris explains. “It challenges them to then think beyond the mainstream civil rights narrative, to include the ‘ordinary’ people who changed the country, often at great personal cost, and to understand that the movement was much longer than just a turbulent decade between 1950 and 1960.”

Norris leads Carolina K-12, a UNC organization focused on connecting teachers to university resources through programs like this one — the Carolina Oral History Teaching Fellowship. Having just wrapped up its second year in June, the initiative brings teachers from across the state to Carolina for a week of professional development activities that deepen their understanding of a particular topic and introduce them to the power of oral history testimony available through the Southern Oral History Program’s (SOHP) collection of more than 6000 interviews. Teachers learn how to navigate the University Libraries database, listen to talks from professors, and develop activities and lesson plans to bring back to their classrooms.

“Universities are incredible treasure troves of resources,” Norris says. “And teachers just don’t know about it. Even if they do, it can be really hard to find the time to cull through these vast collections. It’s like looking for a needle in a haystack.”

Local learning

A former R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company worker discusses the events surrounding the 1947 strike for better wages. A Jewish immigrant shares her experience in moving to Durham’s Trinity Park neighborhood in the late 1940s. A pre-World War II radio newscaster explains the moment he learned that the U.S. military’s aircraft technology was lagging behind Europe’s. A community developer for the Coharie Tribe divulges how she became the only female on the tribal board.

These are just a few of the accounts featured in “Mapping Voices of North Carolina’s Past” — an interactive map created by the SOHP to help K-12 educators bring oral histories into their classrooms. The map features soundbites from North Carolinians across the state sharing personal stories about desegregation, women’s leadership, immigration, industrialization, and World War II.

“I knew that oral history could reframe the past for students and help them understand that history happens everywhere,” SOHP Director Rachel Seidman says. “It happens close to home. Your family, your community was involved in ways you probably weren’t aware of.”

In 2015, Seidman invited a group of local teachers to UNC to ask them if they could utilize the oral history program’s resources. The simple answer was yes — but the educators lacked the time to sift through the hours-long interviews to find clips to share in the classroom. They needed short, curated excerpts for topics they were already teaching.

With help from Carolina K-12 and University Libraries, the SOHP team developed an interactive map with discussion guides on topics the teachers covered in their classrooms. While the map has been an incredible tool for teachers, Seidman felt it wasn’t enough. The SOHP could do more. She teamed up with Norris and Lloyd Kramer, a history professor and director of Carolina Public Humanities, where Carolina K-12 is based, to develop the Carolina Oral History Teaching Fellowship.

This year’s fellowship featured presentations from people like American studies professor Seth Kotch, SOHP founder Jacquelyn Dowd Hall, and UNC Librarian Sarah Carrier, who taught participants how to find local newspaper clippings and photographs through University Libraries and incorporate them into lesson plans.

“Those are the types of things that make classes pop and come alive,” Norris says. “Whether you’re reading ‘To Kill a Mockingbird’ or teaching the Civil Rights Movement, to bring in local voices from a student’s community or state – that really shows we are all making history. History isn’t just the big names in the stuffy textbooks. History is ordinary people doing extraordinary things.”

“We are trying to make the research that lives here at the university available to and useful to a broad public audience across the state,” Seidmans adds. “This really embodies the mission of the university to be of service to the state.”

Creating comradery

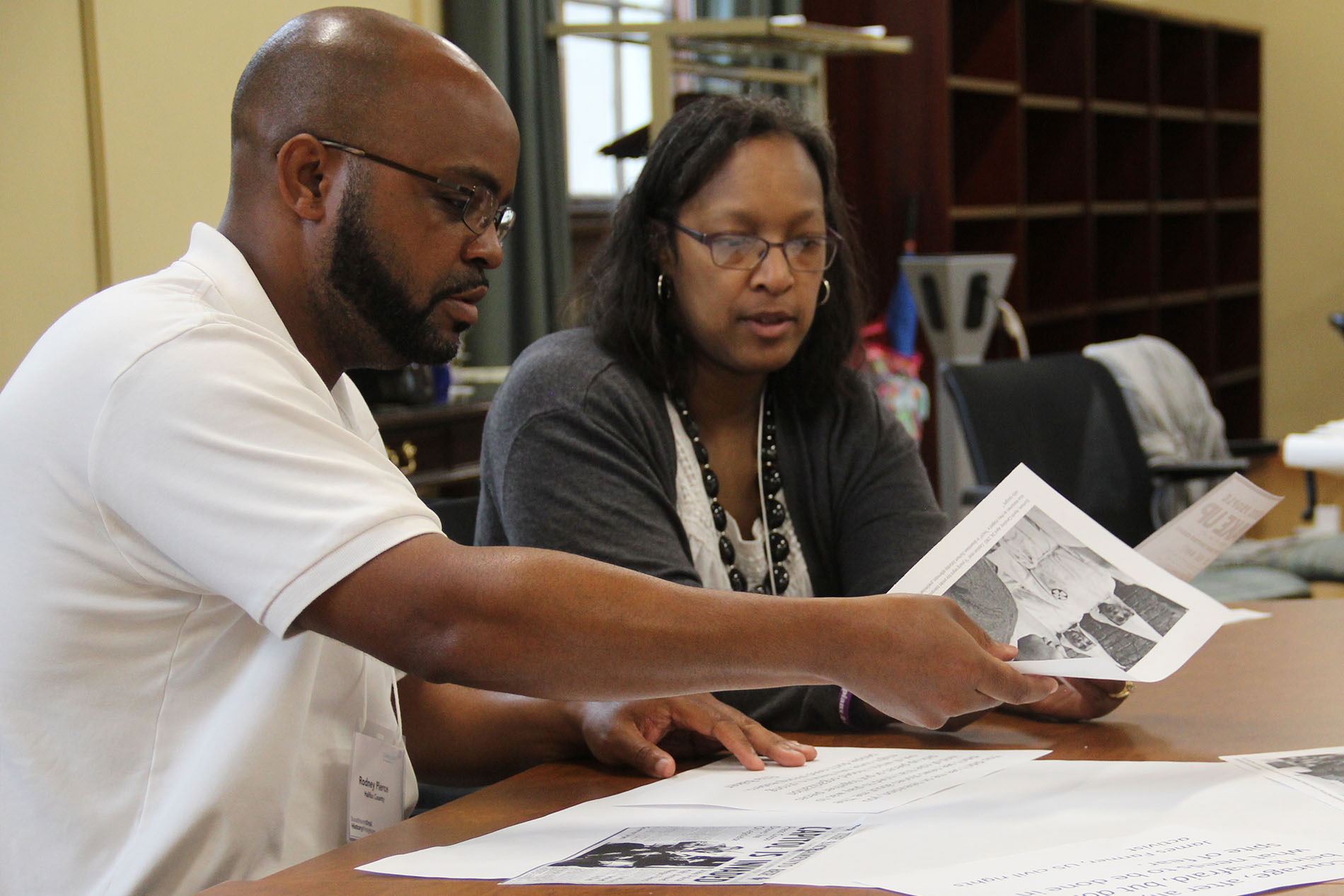

Rodney Pierce, an eighth-grade social studies teacher at William R. Davie Middle STEM Academy in Halifax County, can’t believe he was accepted as a 2018 fellow. “My jaw dropped when I read the acceptance email,” he says. “To get a fellowship at UNC is big time. I grew up in North Carolina, so I’ve always held UNC to a high standard academically.”

At this year’s fellowship, Pierce shared his research on lynchings in Halifax County with American studies professor Seth Kotch, who presented on “A Red Record” — a research project that documents lynchings in the American South. Kotch plans to include Pierce’s findings in his new book.

“For people of Kotch’s stature to recognize my work and find it incredible — that’s a feeling I really can’t explain,” Pierce shares. “It validates you because you work so hard on this stuff in your own time. This is my passion.”

The biggest benefit, according to Pierce, is the relationships developed with fellow educators. “The stuff we are taught and the materials we are given access to — that’s all great,” he points out. “But to be real with you, the best part is the comradery you develop with different teachers from across the state and professors at UNC. The confidence boost you get — these people are so supportive. They recognize your work and know how important it is.”