On March 11, 2020, Rachel Woodul sat at a table in a Chapel Hill restaurant called the Root Cellar, writing the conclusion to her master’s thesis in geography. She had spent the past two years working on a hypothetical model for what hospital capacity would look like if the 1918 Spanish flu occurred in present day.

“Despite extensive and on-going research on pandemic influenza preparedness planning, there is a surprising dearth of literature regarding who is most at risk to dying from influenza, where this risk is concentrated, and why. The results of this study suggest that should a pandemic comparable to the 1918 Spanish flu happen today, when the differentiating effects of receiving health care are considered, the mortality impacts of such a pandemic would be worse than what would be expected based on historical rates alone.”

Woodul’s phone pinged. A news alert lit up the screen: World Health Organization declares SARS-CoV-2 outbreak a pandemic.

Woodul spent the next three weeks rewriting her introduction and conclusion, weaving what public health experts knew at the time about COVID-19 throughout the rest of her draft.

“I was kind of, at this point, feeling panicked,” she admits, worrying less about her thesis and more about the virus itself. “The virus was getting out of control, and we weren’t taking action. In the U.S. specifically, we weren’t doing the basic things that I knew we were capable of.”

It was like watching a train speeding toward a cliff — and not being able to stop it. Woodul renamed her thesis defense: “It’s Going to Be Bad.”

One year later, Woodul continues to study pandemics. Now, as a PhD student in Carolina’s geography department, she’s researching how different approaches to the COVID-19 pandemic may have changed the virus’ course. What would have happened if a mask mandate had been enforced nationally? How could vaccine rollout be improved? What lessons can we learn now to do better in the future?

The hypothesis

Considered one of the worst pandemics in world history, the 1918 Spanish flu killed more than 50 million people globally. Americans represented about 675,000 of those deaths. When Woodul began researching the history of this deadly disease in 2017, she wondered what those numbers would look like today, with a world population of over 7.6 billion people.

More specifically, she was interested in hospital capacity. Could today’s hospitals handle the numbers from 1918? And, more importantly, could they handle them when adjusted to today’s population?

Woodul developed a computational model to evaluate disease outbreak and hospital surge capacity in the Raleigh-Durham-Chapel Hill metropolitan area. She mapped the locations of local hospitals and considered factors like how far people live from such facilities, infection spread, recovery time, and pandemic length.

After 200 days, the number of new infections in her model rapidly increased. On day 368, they finally peaked. After 731 days — the length of the 1918 Spanish flu — Woodul estimated the total number of people who’d require hospitalization to be just shy of 400,000.

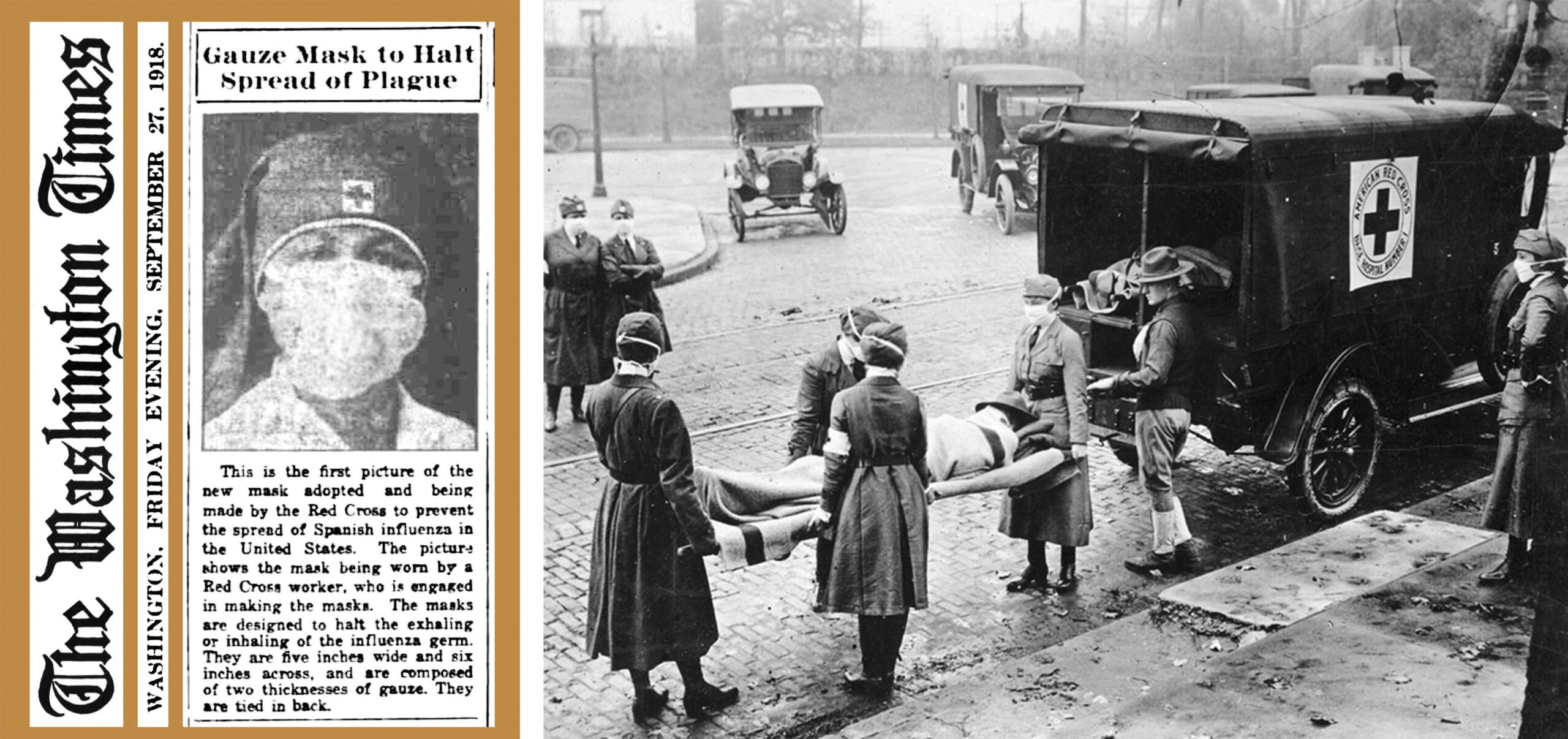

Left: A September 1918 newspaper clipping from The Washington Times shows a new double-layer gauze mask created by an American Red Cross worker to prevent the spread of Spanish influenza. Right: American Red Cross workers remove a flu victim from their house in St Louis, Missouri. (photos from Wikimedia Commons)

Using these numbers, she then considered three scenarios: one in which all hospital beds are available, another where hospital capacity is twice the number of licensed beds, and a third where only 75 percent of beds are open.

What Woodul discovered is that the Triangle, which has more than 14 hospitals and houses most of the state’s hospital beds, would be overwhelmed during such an event. The only scenario that might prevent maximum capacity is to have twice as many beds and to serve only pandemic patients — which is basically impossible to achieve, according to Woodul.

“Where you live matters,” she stresses. “We have some of the best medical care in the world available to us here in the Triangle, and the pandemic has still been devastating. Facilities have filled up quickly and some have hit maximum capacity. But it has been so much worse in other communities, especially communities of color and those in more rural parts of the state and country. Devastating doesn’t even begin to describe it.”

Woodul admits that her approach was subject to several limitations and didn’t include factors like socioeconomic status, car ownership, and other variables that impact a person’s ability to seek care. But she no longer needs a model. A pandemic rages in real time.

“Whether we realize it not, research is never just numbers and figures and words,” her thesis intro reads. “It is the real world, simplified so that we might answer some question, but it remains real nonetheless.”

The reality

Today, March 11, marks day 365 since the WHO declared COVID-19 a pandemic. So far, about 876,000 people have been diagnosed in North Carolina. That number is nearly 29 million for the entire United States and 117 million for the world. Globally, about 2.6 million people have died.

Total hospitalization numbers are trickier to identify. That’s because only two-thirds of states and territories report cumulative data.

While it’s unclear how many hospital beds are actually in the U.S., the American Hospital Association estimates that there are about 728,000. Even before SARS-CoV-2 was declared a pandemic last March, two-thirds of the nation’s hospital beds were occupied.

Right now, there are 35,305 people in the United States who are hospitalized because of COVID-19. Nearly 1,200 are in North Carolina. The numbers are looking much better, even hopeful, Woodul points out. But hospitals still have a lot of other functions beyond pandemic recovery — and that’s what continues to make the landscape so difficult to navigate.

“Hospitals are where people have babies. They’re where people go if they break their leg riding their bike. They provide basic services in our society,” Woodul says. “So if you fill up the hospital with pandemic victims, you can’t deliver babies, you can’t fix broken legs, you can’t help someone who had a heart attack.”

While COVID-19 numbers are still better than those of the 1918 Spanish flu, Woodul feels that the social environment is similar. The infrastructure, funding, and political motivation to effectively respond to a pandemic is lacking.

“Despite all of the research and TED Talks and books and papers and models and war-gaming and months of advance warning and the highest score in the world on the Global Health Security Index, when the U.S. was finally tested by this virus, we failed,” she writes in her thesis. “I’ve spent a lot of time reflecting on this failure in the context of my own research.”

Woodul isn’t the only researcher who feels this way. She points to an article from The Atlantic in which a Georgetown University professor shared a similar sentiment — that researchers unconsciously build a bias into their models that assumes the U.S. is prepared for a public health crisis like this one.

The mistakes made 100 years ago seem more valid in retrospect. Virology was still a relatively new field, and the first flu vaccine wouldn’t be invented for another 20 years.

That said, the government at the time downplayed the Spanish flu’s severity to preserve support for World War I. A similar thing happened 60 years later, at the start of the HIV/AIDS pandemic. Now, one year into the pandemic, there’s still no federal mask mandate in place.

The way forward

Woodul has shifted her research to focus on the lessons learned from SARS-CoV-2, modeling the different approaches the U.S. could have taken along the way. She’s particularly interested in how to communicate public health information to different audiences.

“We need messaging that meets people where they’re at and gets them to follow the guidelines while not insulting their value system or priorities,” she says.

Woodul believes that telling Americans to wear a mask for each other didn’t work, because we are a rather individualistic nation. A message like “wear a mask for yourself to signify to other people that they should wear a mask for you” may have been more effective, she says.

One thing that makes the COVID-19 pandemic unique from others is the rollout of a vaccine less than a year later. But that, too, requires effective messaging.

“The more people we get on board with interventions and with spreading accurate information about vaccines, the better,” Woodul says.

Mathematically, the virus will eventually reach its threshold — a fact that provides Woodul with some reassurance. But when it reaches that threshold is largely up to us.

“Our behavior determines that, and if we behave in a way that limits the number of susceptible individuals the virus has access to, the end will come quicker,” she says. “This isn’t something we will be living through forever. The light at the end of the tunnel is getting brighter — but it’s up to us how fast that happens.”