Listen to the story:

Optimists believe AI will be powerful enough to run the world one day. It will create safer driving conditions, automate some jobs, and even conduct life-saving medical procedures. It will change humankind for the better, improving our systems and helping us live longer, healthier lives.

Pessimists think AI will expand beyond our control and eventually take over humanity. It will be a Sci-Fi movie made real. Think “The Matrix,” “I, Robot,” or “Wall-E.”

But for Mohammad Jarrahi, a self-described realist, neither of these scenarios plays out. He sits somewhere in the middle, finding balance in what AI can really achieve in practice.

“Both scenarios are overhyped perspectives,” he shares. “Emotional intelligence is our capability — and technology cannot understand emotional intelligence the way we can. Creativity and critical thinking are still ours. AI can remove the drudgery — the mundane, repetitive tasks that aren’t a source of human learning.”

As a professor in the UNC School of Information and Library Science, Jarrahi studies human-AI symbiosis. Just like in biology, it is the concept of two different species complementing one another and aiding survival. In this case, the two species are real and artificial.

“It is not competition or cooperation — it’s both,” he says. “It’s coopetition. We need to collaborate with the AI and be mindful that it is not our friend. If we can move past the fear and the hype, we can figure out how AI can realistically help us.”

A sociotechnical surgeon

Jarrahi grew up in the 1990s, during the rise of the web. He began programming in high school and even helped the school get its report cards online. Shortly after enrolling in college in 2000, the dotcom bubble burst and a slew of internet companies failed. Jarrahi was fascinated by it all.

“My father was an IT manager, and he influenced me to go beyond programming and technological aspects to learn about the management of information systems rather than developing them,” he shares. “A strong understanding of both the social context of an organization and the technology is what creates positive outcomes.”

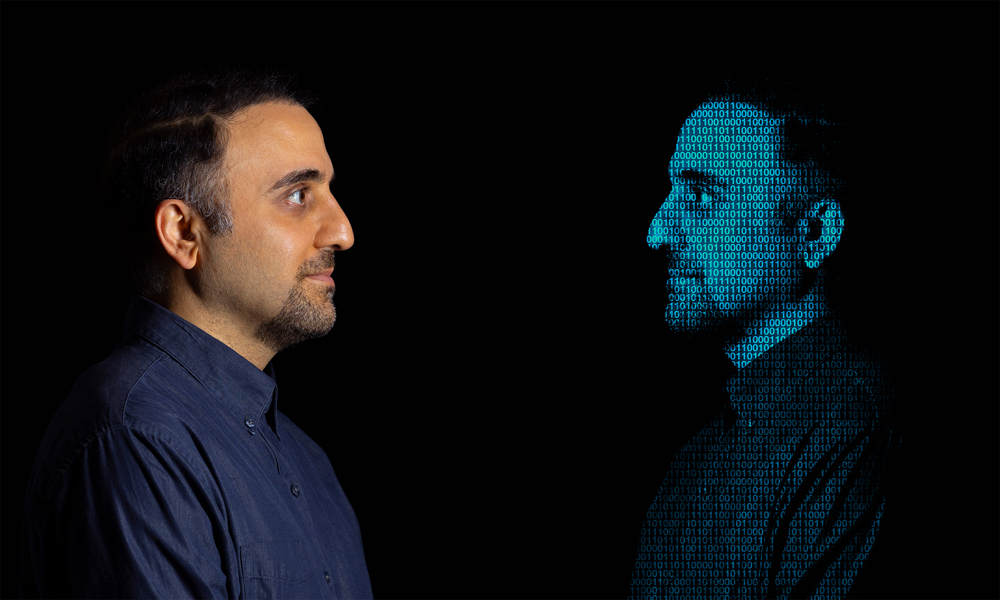

Mohammad Jarrahi (photo by Megan Mendenhall)

Jarrahi went on to pursue a master’s in analysis, design, and management of information systems from the London School of Economics and a PhD in information science and technology from Syracuse University.

Now, Jarrahi studies how information systems — technologies that inform our life and work — play a role in shaping relationships, culture, organizational structure, and team dynamics in the workplace. He wants to understand how AI is changing these spaces and what that means for the future of work.

Jarrahi’s research in this space is largely influenced by the “sociotechnical tradition.” To explain what this is, he says to imagine a patient who needs an artificial heart transplant. Bioengineers develop the new heart and have the most knowledge about how it works. But they don’t know how to install it — that’s where the surgeon comes in.

“I tell my students, ‘You are the surgeon.’ That’s the sociotechnical researcher,” he says. “You need to understand the technology — the heart — and how to transplant that technology into a bigger organic system.”

Human versus AI

Jarrahi’s research unpacks why AI systems should be designed to strengthen human contributions in the workplace — not replace them.

“AI is a very powerful horse that you must first tame, but you can hop on it now and go very fast,” he says. “It’s a process of taming and taking advantage of the horse. The minute you don’t pay attention, the horse will bring you down.”

Inspired by J.C.R. Licklider, a psychologist and computer scientist who coined the term “man-computer symbiosis” in 1960, Jarrahi brings the concept into the 21st century and creates his own version: human-AI symbiosis.

He points to a recent study using images of lymph nodes to detect cancer as an example. A strict AI approach for processing the images led to a 7.5% error rate, while pathologists’ examination had a 3.5% error rate. But when the AI and human doctors combined their efforts, that number was reduced to 0.5%.

One of Jarrahi’s most-cited papers to date is “Artificial intelligence and the future of work: Human-AI symbiosis in organizational decision making,” published in the academic journal Business Horizons, which awarded it best article of 2018. In it, he defines two types of workplace decision-making: analytical and intuitive. The former involves collecting and analyzing information with reason and logic, tasks that AI technology excels at. Intuitive decision-making requires imagination, creativity, and gut instinct — intrinsically human characteristics.

Then, he describes three big challenges organizations face and the human and AI traits required to solve them: uncertainty, complexity, and equivocality.

Uncertainty is when a decision presents many alternatives and unforeseen outcomes.

Imagine a company looking at two possible corporate investors. One is a startup that can’t offer a lot of money up front but will ultimately allow more freedom to pursue new ideas. The other is an established corporation that will pay more, but they have specific guidelines for what they want to achieve in the next three years.

AI can assess these investors using data from each to weigh their pros and cons. It will pick the most logical option on paper. The company’s owners will be more subjective and will try to get to know the people they’d be working with and think critically about how those relationships will affect their goals. The combination of both methods will lead to a better outcome than just one.

Complexity refers to complicated situations with a lot of variables. AI will always be able to process heavier data loads than humans can handle. But humans can choose where to look for and gather that data from, informing what feeds the AI.

Lastly, equivocality involves decisions among multiple parties who can’t agree on a plan of action. When this happens, humans can negotiate, build consensus, and rally support. AI can analyze those sentiments and provide diverse interpretations.

“Although AI capabilities help humans overcome complexity through the machines’ superior analytical approach, the role of human decisionmakers and their intuition in dealing with uncertainty, and especially equivocality of decision-making, remains unquestionable,” Jarrahi writes.

AI’s future in the workplace

In addition to writing perspectives, Jarrahi is conducting a qualitative study on how generative AI systems are transforming jobs for knowledge workers — people who use their expertise and critical thinking to solve problems, develop products and services, or create strategies. He wants to uncover how knowledge workers engage with the technology.

Study participants created digital diaries about how they’re using ChatGPT at work, along with the bottlenecks, pain points, and opportunities it creates. After analyzing these responses, Jarrahi and his team conduct follow-up interviews to learn more.

So far, he’s discovered that a lot of workers are using it for proofreading, ideation, and basic information synthesis — but they have to continuously verify the results.

“Lawyers are using it. Programmers are using it to write some basic code,” he says. “The idea is you need a knowledge worker to use that piece of advice, text, or code to embed it into a bigger organizational process. It’s a powerful toolkit that can do magic, but that magic is not self-driving.”

Jarrahi himself uses ChatGPT in his own writing to organize his ideas into a more cohesive text with good structure and flow. But he stresses the need to proofread what the AI produces because sometimes it deletes important points or adds nonsense.

“These technologies are not going to replace us,” he says. “They are going to reinvent our work — and we have to reinvent ourselves.”