“Unique opportunity lies in the way in which [someone] bears his burden.”

– Viktor Frankl, psychiatrist and Holocaust survivor

In the summer of 2009, Susan Owen visited her doctor for treatment of a relentless cough from seasonal allergies. Her physician ordered a chest X-ray, the results of which concerned him — so he sent her to the hospital for an MRI. By week’s end, Susan received devastating news: She had stage IV lung cancer that had already spread to her bones and brain. She passed away just months later, leaving behind two children under the age of 10 and her husband, Karl.

Karl knew for months that Susan was going to die — but that knowledge did little to prepare him for what followed. Single parenthood. The struggle of returning to work. Maintaining relationships with friends and family.

“Susan and I needed one of the doctors, or someone, to sit us down, encourage us to have those difficult conversations, and give us some practical advice,” he reflected years later. “I’m sure that’s very hard for a lot of doctors to do and maybe some don’t see it as their responsibility. But to me, that’s an essential thing to do when someone is dying.”

Karl’s struggle to cope was obvious, according to Justin Yopp, Susan’s psychologist. But the resources available to help him were less so. After searching for support groups and finding little to nothing in the widowed parent realm, Yopp and colleague Don Rosenstein invited Karl and a man named Joe — the husband of another patient who had recently passed away from cancer — out for pizza. Although the two men had never met before, they connected almost immediately over the loss of their wives.

“One would say something he was feeling or experiencing and the other would nod his head in agreement,” Yopp says. “It was a brief glimpse of what a support group for these men could look like.”

In October 2010, Rosenstein and Yopp hosted the first meeting of the Single Fathers Due to Cancer Program. What began as a short-term intervention evolved into a four-year, monthly meeting of seven men that bonded them for life. Handshakes became hugs. And conversations lasted well past meeting time, overflowing into the parking lot.

To share that camaraderie and sense of hope with the world, Rosenstein and Yopp chronicled their experience with these men in a book — “The Group: Seven Widowed Fathers Reimagine Life.” While it’s written by researchers, it’s not traditional academic literature. It tells a story — one meant to let other widowed fathers, as well as anyone coping with loss and adaptation, know they’re not alone.

“We really just wanted to write a book that people would read,” Yopp stresses. “This is not a how-to book. It’s a how-they-did-it book. And in that way, it’s instructive and, hopefully, enlightening.”

The first meeting

Karl and Joe were the first men to join the Single Fathers Due to Cancer Program. Finding others to participate, though, created a challenge — one that remains prevalent for Rosenstein and Yopp to this day. “There’s no index or list of widowed fathers out there,” Yopp says. “And once their wives had died they weren’t connected to any hospital. So we had to spread the word.”

“The last place any of these guys wanted to come was back to the hospital,” Rosenstein, a UNC psychiatrist, adds. “So they kind of scatter.”

But because both researchers work within the UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Program — which helps patients, caregivers and families with cancer treatment, recovery, and survivorship — they were able to rally five more men into their novel group.

The toughest meeting was the first, when each member shared the story of his wife’s diagnosis, treatment, and passing.

“Even though we knew it would be heavy when the men told their stories — hearing what they were going through struck each of us,” Yopp admits. “We knew this was a sad subject going in, but the amount of loss and uncertainty shared was eye-opening. And it made us wonder if this would be the first and last session.”

But the men returned. At the second meeting, the topic of conversation shifted to present-day problems in their new role as sole caregivers. One of the group members, Neill, shared the dilemma of wanting to honor the one-year anniversary of his wife’s death by spending the day with his four kids — the oldest of whom wanted to hang out with her friends at a hockey game instead. The men suggested he compromise with his daughter, asking her to spend part of the day with the family and then letting her go to the game in the evening.

“We had actually planned some kind of mini-lecture about the developmental aspects of grief for that meeting,” Rosenstein points out. “Then Neill walks in and basically says, I’ve got a real problem right now and I don’t know what to do. Any ideas guys? That really set the tone for how the group worked going forward.”

Past and future

Memories of Susan plagued Karl’s mind for months after her death, and he struggled to focus on taking care of his children — as if the past and present were playing a ceaseless game of tug of war. During this time, he tried to assess his emotions using the five stages of grief, a popular “cultural lexicon” that suggests grief begins with denial and is followed by anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance.

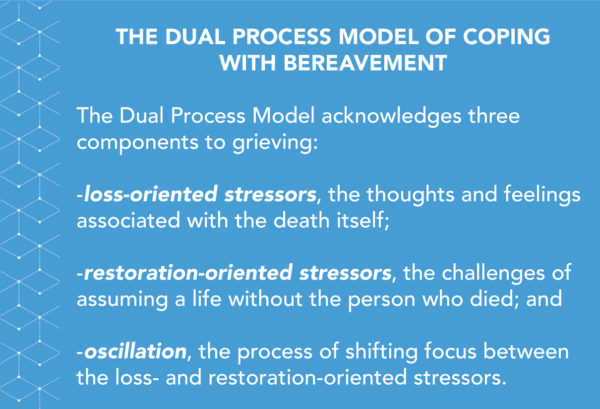

In their book, Rosenstein and Yopp point out the flaws of the five stages of grief. Developed by University of Chicago psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross in the late 1960s, the model seems rigid, as if it’s categorizing people’s grief via one-size-fits-all labels. But it’s more complicated than that. About one year after the group began meeting, the duo discovered a more flexible guide for processing grief created by Utrecht University psychologists Margaret Stroebe and Henk Schut in the late 1990s — the Dual Process Model of Coping with Bereavement.

“It is a theory that addresses the dynamic nature of grief rather than the linear nature,” Rosenstein says. “In other words, it accounts for the fact that people look backward at what they’ve lost and are challenged by the obstacles going forward after the loss. It’s forward and backward.”

“It is a theory that addresses the dynamic nature of grief rather than the linear nature,” Rosenstein says. “In other words, it accounts for the fact that people look backward at what they’ve lost and are challenged by the obstacles going forward after the loss. It’s forward and backward.”

“Grief is complex and disorienting and no one really feels like they know how to do it or what they should be doing,” Yopp explains. “And I think the Dual Process Model carries a little bit of the message that it’s okay to go back and forth.”

While Kübler-Ross’s five stages of grief might make people feel as if they’re regressing, the Dual Process Model helps them understand that’s not the case. Regression is part of the process.

Silver lining

With tragedy comes perspective — and with perspective comes growth. Specifically, something called posttraumatic growth. If that sounds familiar, it’s probably because you’re thinking about posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). But the two are not mutually exclusive. Posttraumatic growth can actually complement PTSD, acting as its equal.

“Posttraumatic growth is when you go through a traumatic experience and, after some time, you can reflect on it and see how you’ve grown as a result of that trauma,” Yopp explains. Experiencing posttraumatic growth, though, does not mean you’re free of stress or glad the trauma happened.

“It’s like what my grandmother used to say: It’s what builds character,” Rosenstein says. “You don’t want to have gone through that traumatic experience — but maybe you have more wisdom. You have more skills in your toolbox for dealing with adversity. It’s the strength in character that you develop from the wounds.”

Rosenstein and Yopp saw a lot of examples of how these seven men grew as a result of their trauma, grew because they needed to step up as the only parent in their household — and, in turn, help their children grow. In the book, one of the men, Bruce, admits: “I desperately hate being a widower, but I love that I’ve grown closer with my kids as a result.”

The men’s children, in particular, were never far from anyone’s mind.

“For me, the biggest reward in all this is knowing that by virtue of helping these parents we help their kids,” Rosenstein says. “With the group, we felt we needed to shore up the dads so that they were more effective, more present, more fun, more forgiving, more whatever than they might have been otherwise.”

Yopp agrees. “How a child responds to the death of a parent is influenced by a lot of factors — and we feel like if you had to pick one way to help a child it’s to help the surviving parent. As hard as it was for these men, as much as they wish they hadn’t had to have gone through this experience, it doesn’t mean there wasn’t some benefit to it.”

Pay it forward

Over the course of four years, the group evolved into something else. The men changed in ways they never thought possible. They became better advocates for their children, themselves, and the stories their wives left behind — and were willing to share this invaluable knowledge with the world.

“They are the experts,” Yopp points out. “They helped us create the website, looked over our research papers, publicized what we were doing with other men, and even helped with writing the book.”

“It became a creative partnership,” Rosenstein adds. “That was very cool — and not expected.”

In fact, many of the men offered to share their stories publicly. Karl shared his observations and feelings surrounding Susan’s illness with medical practitioners at the UNC School of Medicine’s Swartz Center Rounds, a forum on patient care. Russ and Bruce are featured in a 14-minute educational film for healthcare providers called, “If I Should Not Return.” Joe and Karl participated in an article run by The New York Times, and Bruce shared his story on national television via the “TODAY Show.”

Rosenstein (left) and Yopp shared insights about the book with a packed room of people at Flyleaf Books on February 1.

“The collective wisdom of these men came together in such a way that made us realize we can and have to do better for people living with terminal illnesses,” Rosenstein says. “These guys can inform the rest of us about how to do better. They hold all this really important information — something that, as a system, we don’t tap into enough.”

“These men were able to give back and pay it forward in ways they wouldn’t have been able to otherwise,” Yopp says. “The sum was very much greater than the individual parts.”

For any parent

After the original seven ceased meeting in 2014, Rosenstein and Yopp knew they wanted to continue the group with a new cohort of men. But they needed to reevaluate the format to serve more people. They also recognized the benefit of mixed viewpoints — pairing newly widowed fathers with “veterans” — and providing the opportunity for men to opt out when they wanted to.

Today, the group still meets monthly, but now men can join or leave it via one of three designated meetings each year, which means new members can join every four months.

“Some of the veteran fathers will talk about how they’ve grown, and how they’re better in some ways,” Yopp says. “And the newer fathers hear that — and take it more seriously since it comes from a peer.”

Continuing to manage the Single Dads Due to Cancer Program is only one of Rosenstein and Yopp’s goals. More than anything, they want to help anyone who’s lost a partner. That’s why they rebranded their website as www.widowedparent.org — to serve any parent who’s lost a spouse to any cause, not just cancer. It features a survey, videos, and other resources for widowed parents, as well as information for healthcare professionals.

Continuing to manage the Single Dads Due to Cancer Program is only one of Rosenstein and Yopp’s goals. More than anything, they want to help anyone who’s lost a partner. That’s why they rebranded their website as www.widowedparent.org — to serve any parent who’s lost a spouse to any cause, not just cancer. It features a survey, videos, and other resources for widowed parents, as well as information for healthcare professionals.

While Rosenstein and Yopp strive to serve all widowed parents, their all-male group will remain intact.

“The men feel like they can say things to each other that they can’t anywhere else,” says Rosenstein, reflecting back on the meetings with the original seven members. “Sure, they might have done just fine with individual, one-on-one counseling — but there was some kind of magic that happened once a month in that room. It’s the healing power of connectedness. And it was a privilege to watch it, to see these men help each other.”