Just imagine the number of books available at your local library. While they exist in the physical space, there is also a computer system that logs the entire collection — or data that gets ingested when new books arrive, are stored, and then get disseminated when someone files a request. On a grander scale, for example, the National Library of France — the seventh largest library in the world — houses more than 40 million items alone. Simply put, that’s a lot of data.

A decade ago, all people could talk about was the “data deluge.” In fact, in 2010, The Economist released an article with that exact title, reporting that humans created a billion gigabytes of data in 2005 and that 2010 promised to yield eight times that amount. “The data deluge is already starting to transform business, government, science, and everyday life,” the article points out. “It has great potential for good — as long as consumers, companies, and governments make the right choices about when to restrict the flow of data, and when to encourage it.”

The data game is a familiar one at UNC.

The data game is a familiar one at UNC.

“The whole story about the data deluge eight to 10 years ago has now become so pervasive that we don’t talk about big data anymore, we just talk about data,” says Jason Coposky, the executive director of iRODS.

Located within RENCI, iRODS stands for integrated Rule-Oriented Data System. It’s a data management middleware that insulates data against changes in technology. It functions similarly to Google, Coposky says — when it does its job well, users don’t even know it’s there. “It’s basically invisible,” he explains. “And it protects your data because, eventually, your infrastructure is going to change out, or you’ll need to buy new storage so you need to move your data, which is a very difficult thing to do when you’re dealing with petabytes and millions of files.”

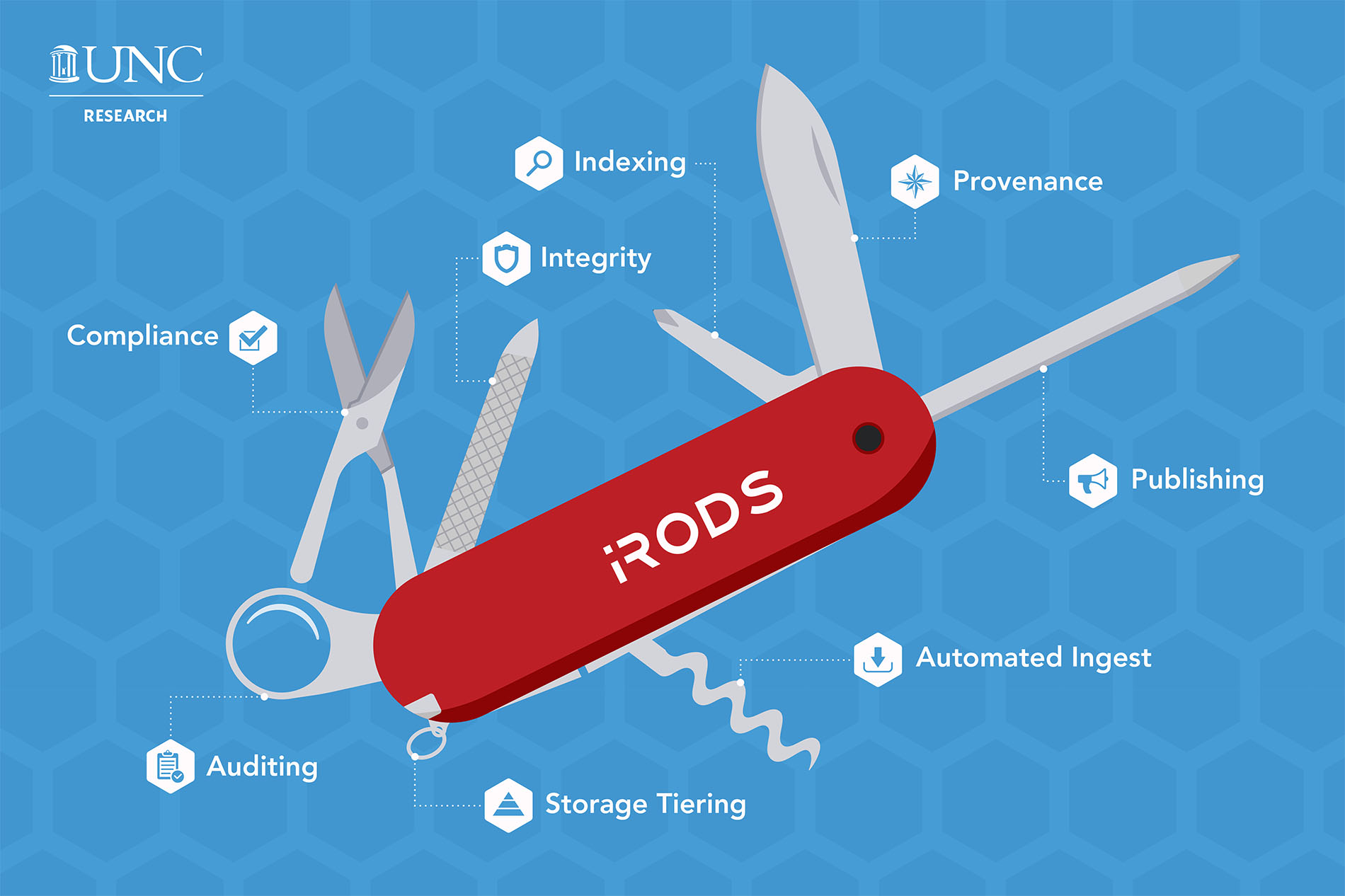

iRODS does a lot more than protect data from aging technology. Think of it like a Swiss Army knife — one tool that accomplishes many things, from the ability to examine the data over time (auditing) to improving the speed of data retrieval operations (indexing) to setting rules for who can and can’t access the data (compliance).

“iRODS helps tell the story of the data from front to back,” Coposky says. It establishes a data management policy — the “secret sauce,” according to Coposky — that can assign data to specific media, folders, and even geographic locations based on organizational needs.

“Telling the story of the data is like telling the story of the glaciers,” RENCI Director Stan Ahalt agrees. “It’s an evolving, living, growing, breathing, changing thing. And if you want to keep track of those changes, there has to be some way to write the history. A log of all those changes is a powerful way of capturing the evolution of the data.”

But iRODS didn’t always have those capabilities. In 1995, when Reagan Moore and his team at the San Diego Supercomputer Center first developed the software, it was nothing more than a file system for physics simulations. “At the time, these particle physicists were generating reams of data on a bunch of different computers and they needed a way to tie it all together,” Coposky says. The policy component came later, when Moore’s group began the next generation of software with a complete rewrite. Shortly after, the team relocated to UNC.

Coposky joined the iRODS team in 2010 as lead developer. After the consortium began in 2013, he transitioned to chief technologist, restructuring and coding the software. Now, as executive director, he spends a lot of time on the road, attending conferences, visiting customer sites, and “spreading the good word” about iRODS.

Today, iRODS provides a data backbone for major research projects such as Hydroshare — a National Science Foundation-funded, open-source platform for hydrologic data and model sharing — and the National Institutes of Health Data Commons, a shared virtual space where biomedical researchers can easily and securely work with data, analytical tools, and applications.

It is also utilized by a variety of major institutions, from the Max Planck Institute for Plasma Physics to the Library of France. “Libraries use it to curate data the same way they would physical artifacts,” Coposky says. iRODS is also experiencing growth among life science companies and has acquired several notable clients like Bayer, the Wellcome Trust Sanger Institute, MSC, Syngenta, and the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Other growing industries include pharmacy and finance, according to Coposky, and the consortium is slated to have 30 members by the end of 2018.

“When scientists can spend less time managing, curating, and transforming data in order to get to the point where they do the actual science and not spend their time massaging data, everybody wins,” Coposky says. “The same can be said for any enterprise entity that manages data at large scales. That’s why RENCI has transformed iRODS, taking what was effectively a science project and turning that into an enterprise product.”

A global network

Today, iRODS is open-source, which means it’s customizable and fully accessible to the public. It’s used by universities, research organizations, businesses, and government agencies across the globe — so many that, in the last decade, RENCI had to develop a plan to sustain its use. So, in 2012, the institute created the iRODS Consortium, comprised of members who want to see the software evolve and the user base grow.

Before learning about iRODS, researchers at Utrecht University in the Netherlands would deposit and store their data on faculty network shares and local external disk drives — a process that led to unmanageable data deluge and lost information.

“iRODS allows us to safeguard and manage massive amounts of data on an information management level rather than at the data storage level,” Ton Smeele, an IT data management specialist at the university, says. To make iRODS even more effective for researchers, he explains, the university has combined its functions with a web application called “YODA ” — short for Your Data — to create a user-friendly interface.

“With YODA, my research group can work together on our data, manage access, and easily and neatly archive and publish our data,” says Vincent Buskens, a professor of sociology and institutions at Utrecht University. “These used to be separate processes, but now we avoid double work and have safer storage.” The publishing component is especially helpful, Buskens points out, as a growing number of academic journals now require it to maintain integrity and transparency.

Researchers who utilize iRODS also stand a better chance of obtaining grants. “They can prove that they manage data safely and in line with the FAIR Data Principles,” Smeele says. Such principles help make data findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable.

“A little bit of everything”

iRODS’s success stems from the fact that it’s multipurpose, Coposky says. “It does a little bit of everything for everybody. It’s really a question of how you want to use it.” Over time, clients explained how they could use the software more extensively if it had certain characteristics it didn’t have in its original form.

“So we modified it,” Ahalt says. “And made some pretty extensive changes to the code base. It really creates a platform that, by writing rules you can construct a data management universe.”

“We’ve taken what was once a custom implementation for every one of our users and put those into boxes in a way that they can just be taken off the shelf and installed and configured,” Coposky adds.

For the future, both Coposky and Ahalt hope to see the community utilizing this software grow — ideally through an industry closer to the public sphere. And with 2.5 quintillion bytes of data at our fingertips daily, they may not be far from that goal.

“It’s not really about the number of members for the consortium,” Coposky says. “It’s about building a community around all of this.”