A med technician at the UNC Biomedical Imaging Research Center (BRIC) — one of three university centers in the country with a PET/MR scanner — inserts an IV into the left arm of a woman wearing a hospital gown and leads her into the next room. The patient lies down on a table, which, after a few minutes, begins to move backward into a confined dome. The tech injects a fluid into her IV. The faint thrumming of machinery creates a din in the background. The patient relaxes and remains almost perfectly still for 80 minutes so researchers can see when and where the fluid inserted into her IV enters her brain.

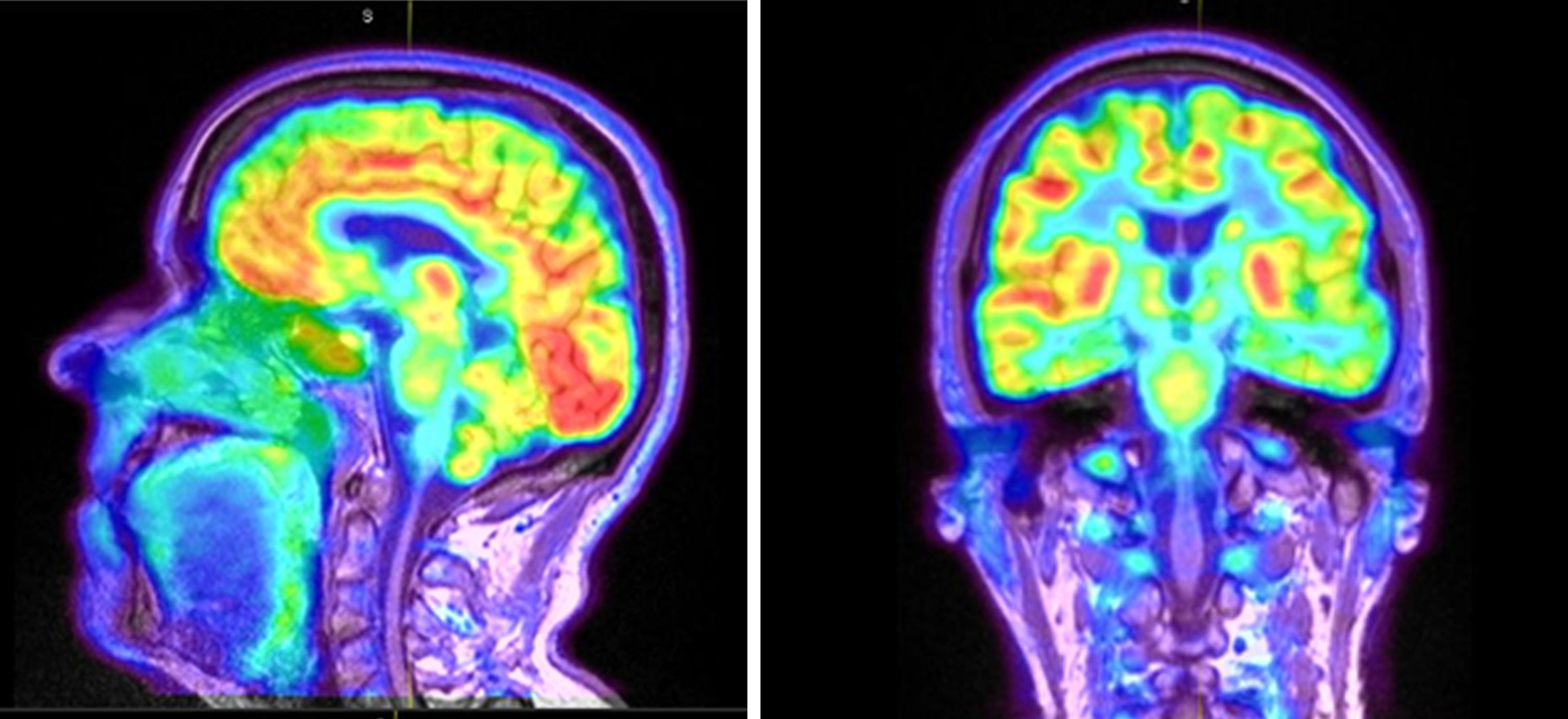

The PET/MR scanner allows researchers to observe the functions and structure of the brain including its volume, thickness, and surface. It’s one of the reasons psychology and neuroscience professor Kelly Giovanello was drawn to UNC-Chapel Hill 10 years ago.

Giovanello studies human memory and changes in the brain like those caused by Alzheimer’s disease. Specifically, she observes two types of proteins that form in the spaces between the brain’s nerve cells and impair memory and function. To do so, she and her team in the Cognitive Neuroscience of Memory Laboratory use ligands — molecules that attach to these proteins in order to show, using the PET/MR scanner, where they reside in the brain.

“My goal is to figure out who will develop Alzheimer’s disease,” she explains, “and to be able to diagnose it.” Alzheimer’s disease can, currently, only be diagnosed during autopsies, after someone has died — a hard thought to digest, considering it affects more than 5 million people in the United States, according to the Alzheimer’s Association. “And that number is expected to quadruple by 2050,” Giovanello says. “The number-one risk factor for Alzheimer’s is age, and baby boomers and older adults are living longer.”

Giovanello sees study participants at all levels of risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Brain scan comparisons of people who have healthy brains versus those who have a mild cognitive impairment, she believes, will help her and her team discover who will ultimately develop the disease. “The new frontier of Alzheimer’s is very early identification of the disease,” she explains. “We want to be able to diagnose someone before they begin having memory symptoms.”

Breaching the barrier

A series of vessels surrounding the brain create an effect similar to that of the Great Wall of China, according to pharmacy professor Elena Batrakova. Called the blood brain barrier, this “wall” is made up of very long vessels that are difficult to penetrate — and their role is to keep harmful toxins away from the brain. That’s why treatment for diseases in the brain has been so incredibly difficult for researchers. But Batrakova has found a way to get past the brain’s defenses.

Macrophages — a type of white blood cell — cross the blood brain barrier to reduce inflammation. Batrakova can load live versions of these cells with antioxidants like catalase, which are known to remove harmful substances from the body. In this particular case, Batrakova hopes the antioxidants will deactivate neuron-killing free radicals. Once the macrophages are loaded, she injects them intravenously back into the patient.

“When free radicals kill neurons,” Batrakova says, “the cells die and cause inflammation. The macrophages know where to go because they are immune response cells; they can sense where the inflammation is and deliver the drug there.”

After seeing the success of this process, Batrakova felt she and her team of researchers could take it one step further. She thought: Why don’t we inject these macrophages with DNA that can synthesize catalase? “It’s a much more beautiful story this time around,” she laughs. “We can deliver more catalase this way.”

Again, she took it further: exosomes. Macrophages naturally release exosomes — proteins that adhere to the surfaces of membranes and transfer molecules from one cell to another. “When scientists first discovered exosomes, they thought they were trash bags — that their job was to discard unnecessary proteins and gene material,” Batrakova says. “But one man’s trash is another man’s treasure. It’s a treasure we use as a drug delivery vehicle.”

Instead of loading the macrophages with the drug, Batrakova loaded the exosomes and found that they reach nearly the entire brain. And, because they’re small, they can be administered to patients in the form of nasal spray. “They are small enough to travel through the nerves in the nose to the olfactory pathway and then to the brain,” she points out. Although her research has only been tested on mice, she and her research team are in the process of getting funding and approval for a clinical trial.

Knowing the signs

Talking to a doctor as soon as you or someone you know starts to become more forgetful is the best way to fight this disease, according to Giovanello. She strongly believes early diagnosis is key, and regularly participates in community outreach programs like Morehead Planetarium’s UNC Science Expo to answer questions from community members about Alzheimer’s disease. She stresses the importance of sharing scientific data with the public.

Giovanello also visits a local retirement community each semester to chat with residents about the brain and healthy aging. The best way to keep the brain healthy, she explains, is to stay engaged — mentally, physically, and socially. For example, games like tennis and badminton combine all three.

“People fear Alzheimer’s so much because it’s unpredictable who is going to get it,” Giovanello says. “It’s a disease that deprives you of who you are. If you don’t have your memory, it’s really hard to have a sense of self and identity.”

A lot of people have experienced Alzheimer’s firsthand, whether it’s a family member or a friend — and it’s often these people who volunteer for Giovanello’s research studies. “Not only does the researcher get the benefit of collecting data,” she explains, “but the participants themselves express satisfaction with their involvement in helping scientists understand Alzheimer’s.”