Sarah Almond leans over a large, tattered hospital admissions ledger and squints. While she tries to decipher the 100-year-old-script, Robert Allen scribbles down the name of a patient from Austria. Then, Almond points out a string of housewives all admitted to the hospital at the same time. On the next page, they read how a police officer was checked in for “cocaine use.”

For the past year, UNC Community Histories Workshop researchers have frequented the North Carolina State Archives to delve into records from Dorothea Dix Hospital – North Carolina’s first and largest mental hospital, which closed in 2012. In 2015, the City of Raleigh purchased the 308-acre property to transform it into an enormous public park. When completed, Dorothea Dix Park will be the largest in the city of Raleigh.

With help from researchers like Allen and Almond, the city hopes to incorporate the hospital’s history into the park’s master plan. “If we’re able to connect the past to the future it will really make this place authentic and reflective of the history of Raleigh and the state of North Carolina,” says Kate Pearce, the park’s senior planner and project manager.

Launched in 2016, the Community Histories Workshop links North Carolina communities with their past through adaptive reuse projects incorporating archiving initiatives, oral history, digital resources, and onsite interactive exhibits.

For example, the team has created a digital humanities project about the Rocky Mount Mills, the second oldest cotton mill in North Carolina. This summer, the group is hosting a workshop for middle school teachers about the integration of the mill in the 1960s, based on oral history interviews. With the Southern Historical Collection, they have organized another community event connecting families in the Rocky Mount area with ancestors who operated the mill as slaves. Another initiative includes digital exhibits and investigation into the Native American history surrounding the area. Pearce thought this approach to community history would be a perfect fit for the park.

To build a vast resource of data, the Community Histories Workshop team is examining administrative, admission, and cemetery records, Lunacy Commission Records, and personal and family papers from the state archives, UNC Southern Historical Collection and online databases.

They are also studying the significance of the hospital’s design. The mid-19th century was a turning point for understanding and treating mental health patients, thanks largely to Dorothea Dix. Doctors began to understand mental health issues as a disease, and felt that patients should be safely cared for in specialized facilities. This shift toward “moral medicine” greatly affected patient housing and, therefore, the architecture of the hospital.

They are also studying the significance of the hospital’s design. The mid-19th century was a turning point for understanding and treating mental health patients, thanks largely to Dorothea Dix. Doctors began to understand mental health issues as a disease, and felt that patients should be safely cared for in specialized facilities. This shift toward “moral medicine” greatly affected patient housing and, therefore, the architecture of the hospital.

Allen and Almond have toured the main building and hospital wards, visited other mental institutions from the same era, and researched the hospitals original architect, Alexander Jackson Davis. In the New York Public Library, Almond found letters between Davis and former North Carolina Governor John Motley Morehead about authorizing the planning for the hospital and instructing Davis to visit asylums from New York to Virginia for inspiration.

The bulk of the group’s work, though, is photographing over 7,000 admissions records and transcribing that information into a digital archive.

Decrypting documents

Allen first saw the admission books in 2017 while identifying useful historical materials like annual reports from the hospital’s superintendents.

After a long day of research, an archivist asked Allen if he’d like to take a look at some material that had yet to be catalogued and reviewed by historians.

Allen opened a red leather-bound ledger and saw that it was, in effect, a 19th-century spreadsheet. Every patient admitted to the hospital in its first 50 years of operation was listed, totaling 5,635 individuals.

“Every one of the staff members that was there that day was crowded around that table,” Allen says. “It was like Christmas morning. You opened it up, and I mean, people gasped. This is the Rosetta Stone: This enables us to connect real lives to these entries in the admissions ledger.”

The ledgers date back to the admittance of the first patient in 1856. Each entry states typical patient information – name, age, occupation, marital status, residential county, date of admittance, discharge, and in some cases death.

Allen is especially interested in the supposed causes and diagnoses of patients, and how that connection relates to the understanding of mental health at that time. Love, epilepsy, war, exposure to sun, religious fanaticism, and disappointed ambition: just a few reasons why patients were admitted in the late 19th and early 20th century.

A team of undergraduate research fellows have digitally transcribed each entry up to 1917. In some cases they have been using Ancestry.com, Newspapers.com, patient case histories, and public records to investigate specific people. Because of North Carolina’s open-records law, the team can only publish information more than 100 years old.

Their goal is to trace patients’ history to see what events led people to the hospital – something they believed would be a perfect project for a UNC health humanities class.

Connecting to the classroom

A UNC health humanities class discusses their experiences creating case studies about specific patients at Dorothea Dix Hospital.

“I’m constantly on the lookout for ways that we can connect the work that we’re doing with other units on campus,” Allen says.

During the 2018 Spring semester, students in Health Humanities Intensive Research Practice transcribed and built case studies from hospital entries between 1861 and 1871– a decade overwhelmed by Civil War soldiers returning from battle, consequences of war that could lead to mental health issues, and the first admittance of African Americans to the hospital.

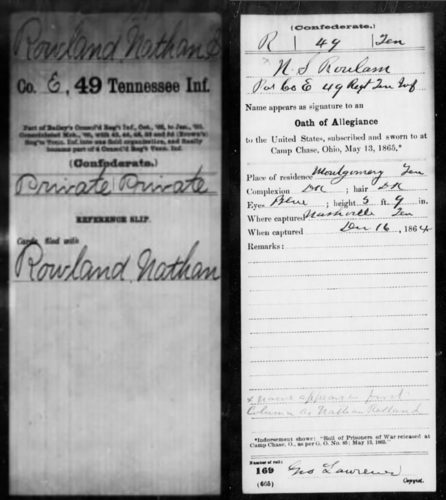

Using Fold3.com, a military database, Emily Long found Nathan Rowland’s enlistment papers, as well as his Oath of Allegiance to the United States after the Union won the Civil War.

Jordynn Jack, the professor over the class, says her students dove into their work wholeheartedly. “They’re not just doing research that’s already been done; they’re doing original research – for them that’s a really valuable thing.”

Emily Long, for example, researched the life of Nathan Rowland, a young man from Morrisville, North Carolina, who fought for the Confederacy.

“I was interested in his experience within a historical context because, to an extent I guess, we’re all products of our time,” Long says.

Working backwards from the admissions ledger, Long found Rowland’s enlistment date and regiment. From there, she researched 10 battles and skirmishes he fought in, as well as his time as a prisoner of war in Illinois and Ohio.

After a three-and-a-half-year enlistment, which was only supposed to last one year, Rowland returned to Wake County. He reported having attacks of mania, but doctors attributed that to cardiac problems. This was often the diagnosis for soldiers experiencing post-traumatic stress disorder at that time: Doctors believed their hearts had been overworked.

In 1866, Rowland was admitted to Dorothea Dix Hospital where he remained for 16 years. Although marked as “unimproved,” and removed from the hospital in 1882, he was readmitted in 1890. The ledger explains that Rowland died in 1909 of “malarial chill.”

Long gathered a detailed, decades-long account of Rowland’s life, but itched to find out more. The experience of uncovering the life of someone who lived over 150 years ago was worth this frustration, she says.

“In a lot of courses, you don’t get to do as much hands-on stuff,” she says. “I thought it was cool we got to go through and try to figure out details of these peoples’ lives and what their experiences might have been like.”

Community Histories Workshop members hope visitors to the park will share that same eagerness to learn.

Preserving the past

Kate Pearce anticipates the park plan will be brought to the Raleigh City Council in the spring of 2019. This framework, which will include Allen’s findings and community input, will be a starting point for the city and the team of design consultants.

The goal is to generate as many ideas as possible, Pearce says, and to think of ways to represent history outside of traditional venues such as a museum.

“Not to say that a museum won’t be there,” she says. “But I think there are a lot of creative ways to use landscape, to use storytelling, to use art to metabolize this history and make it a lot more approachable and relevant to people today.”

Although Allen’s team is currently focused on the hospital, they also want to include research regarding the site’s time as a plantation and even further back as a Native American territory.

“There’s a story there that’s very emotional, that’s not necessarily positive,” Pearce says. “The race history there, the plantation, all these stories need to be told and we need to make sure we do it in the right and respectful way.”

While it’s difficult to not let his mind wander about how their findings will be incorporated into the park, Allen and his team strive to gather as much information as they can.

“Our job is to say: Here are the things that we are discovering that shed light on peoples’ engagement with this place in the past,” he says. “We want to make sure that we have this material and that it can be deployed in as many different ways as responsibly possible.”

Because of the property’s deep-rooted history, many North Carolinians already have a connection to the site. “You can almost say the history of Dix Hospital is the history of the state,” says Lucas Kelley, a UNC PhD student working with the Community Histories Workshop. “It’s such a focal point for the entire state. I think this is a great lens to see the history of North Carolina.”

[row]

[column lg=”6″ md=”12″ sm=”12″ xs=”12″ ]

[/column]

[column lg=”6″ md=”12″ sm=”12″ xs=”12″ ]

Dorothea Dix Cemetery is the burial ground for some patients who died between 1859 and 1970. Most of the graves were unmarked until the 1990s, due to the stigma associated with mental health issues.

[/column]

[/row]