Johna Register spent much of the 1990s playing high school basketball in an old airplane hangar in Slocomb, Alabama. Wooden boards had been laid down on the cement floor to create a court — an innovative way to repurpose an old space, but a poor solution for making a safe basketball court. Consequently, Johna and many of her teammates suffered from horrible shin splints.

“Most basketball courts have a spring-based system underneath, because you run around a lot and want to be able to jump,” she says.

Johna’s leg injuries resulted in a stress fracture. She began working with an athletic trainer to remedy the problem. This exposure to sports medicine gave her insight into a potential career path she could pursue and, just a few years later, she enrolled in the athletic training program at the University of Alabama.

A few years earlier and about 1,500 miles away in Saint-Hubert, Quebec, Jason Mihalik was playing in a tournament for his high school hockey team and tried to sidestep a bodycheck while moving the puck down the ice. The opponent stuck his knee out, slamming it into Jason’s and knocking him down. An athletic therapist on the sidelines came over to assist and diagnosed Jason with a medial collateral ligament injury, often caused when the knee is forced sideways.

Like Johna, Jason decided to use his experience to help others. He attended Concordia University in Montreal, where he majored in exercise science with a specialization in athletic therapy.

“I think if you talk to anyone who’s an athletic trainer, most of us were athletes and had injuries and were exposed to an athletic trainer or something in sports medicine,” Johna says.

Today, Johna and Jason are both professors in the UNC Department of Exercise and Sport Science. Their stories collide far beyond their love of sports: They met at Carolina in 2004, got married in 2006, and have complementary research programs. Johna focuses on the prevention, education, and clinical management of sport- and recreation-related traumatic brain injury, and Jason researches the mechanical aspects of head trauma, concussion assessment and management, and rehabilitation technologies.

While working within the same department provides various challenges, Johna and Jason have navigated the situation like a team sport, seamlessly weaving together their personal and professional lives.

Pursuing similar paths

Johna and Jason’s experiences continued to mimic one another’s from afar during their undergraduate educations. Both worked directly with college sports teams — Johna, the men’s football team and Jason, the women’s hockey team — and both watched athletes undergo a variety of injuries during play. But one injury stood out the most.

“The systematic way I had been taught to evaluate injury didn’t translate to concussion,” Jason remembers. “And it had me very curious — why was this head injury any different from all the different injuries we’d been evaluating?”

A similar thing happened to Johna in Alabama.

“There were a couple cases where a player had many concussions and so it would take them a long time to recover,” she says. “At that time, in the early 2000s, there was a lot of stigma associated with this injury because we couldn’t see it and we didn’t know how badly it affected people.”

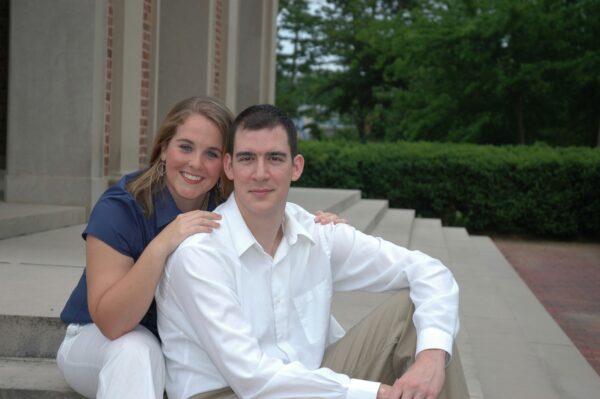

Johna and Jason pose for their engagement photos at the Morehead-Patterson Bell Tower on UNC’s campus. (photo courtesy of Johna and Jason Mihalik)

They both began researching the topic and came across the same name in the scientific literature: Kevin Guskiewicz, a UNC neuroscientist and athletic trainer. Each began corresponding with Guskiewicz via email — Jason just a few years before Johna. After graduating, he enrolled in a master’s program at the University of Pittsburgh and continued to connect with Guskiewicz from afar.

While Jason was working on his master’s at Pitt, Johna was wrapping up her junior year in Alabama. Her emails with Guskiewicz led to a summer internship with his lab in Chapel Hill, where she received a first-hand look at his concussion studies.

“When I left, I had that Carolina blood running through my veins, and I knew I wanted to attend graduate school here,” she says.

By 2004, Johna and Jason’s timelines were fully in-sync: Jason had been accepted to the PhD program and Johna the master’s program. Both arrived at Carolina the same day in August — and both were invited to grab a beer on Franklin Street at He’s Not Here.

“It’s a very Chapel Hill story,” Johna chuckles.

And it wasn’t necessarily love at first sight.

“That first night, Johna will tell you she thought I was weird. And I’ll tell you I thought she was obnoxious,” Jason says.

“Both of those things might still be true,” Johna agrees.

Changing concussion culture

Although Johna and Jason both studied concussion at Carolina under Guskiewicz, they focused on different issues within the field. Johna was interested in public health and wanted to find ways to improve concussion reporting, assessment, management, and prevention — the subject of her master’s thesis and PhD dissertation.

Today, Johna is engaged in multiple studies on these topics. One aims to change the culture of middle school sports to reduce risky behaviors and develop educational strategies for use across all levels of athletics. The goal, she says, is to create an environment that encourages people to seek care.

“Even if we have all these great, innovative treatments, if people don’t work with the health care system, they’re not going to get those treatments and the things we know that work,” she shares.

Previous literature suggests that if an injured person receives care within three days of their concussion, they recover faster than individuals who wait to seek help. Johna wants this to be the norm and is currently overseeing a large clinical trial with participants from the United States, Canada, and New Zealand to evaluate early interventions.

Guskiewicz and Jason pose with Johna upon receiving her PhD at her doctoral hooding ceremony. (photo courtesy of Johna and Jason Mihalik)

“We want to create a culture and environment that not only alters athlete behavior, but clinician behavior,” she says.

Johna has translated this work in the real-world by teaming up with local businesses, athletes, and other stakeholders to create a website that allows individuals to “choose their own adventure.” They can build a concussion pathway by making a series of choices that lead to a potential outcome — which may help athletes and their parents understand what their next steps should be after a concussion, Johna says.

She has also worked with athletic trainers, therapists, and physicians to better identify concussion symptoms and improve the healing process for patients.

Getting inside the head

Jason’s graduate work focused largely on head impact biomechanics — how the head responds to intentional and unintentional hits — in youth hockey players. He also worked on a major project with Guskiewicz, inserting accelerometers into helmets to study head trauma during live football practices and games. They discovered that concussions can occur at a variety of accelerations, from 60 to 169 g-forces.

In the last 10 years, Jason has collaborated with the U.S. Department of Defense to develop a longitudinal brain health program for the U.S. Army Special Operations Command.

“We just didn’t have a better way to see concussions — and they wanted a better way to see them,” Jason says.

Participants in the project undergo an MRI, a special ultrasound that looks at blood flow in the brain, blood tests, and vision and sensory assessments. Because recent research suggests that a concussion can increase risk of musculoskeletal injury and mental health disorders, Jason and his team also measure athletic ability, anxiety, and depression, among other factors.

“So it’s not just a concussion study,” Jason says. “That’s the framework, but we realize that a concussion and traumatic brain injury can cause a whole slew of other secondary conditions that can impact people more so and even longer than the actual injury.”

The information Jason is gathering may eventually be used to help soldiers who want to stay active duty heal and maintain their neurological health and to determine when injury is severe enough to warrant retirement. Jason is also establishing a similar program for veterans in order “to serve those who have served us.”

In 2010, Jason and Johna teamed up with Guskiewicz to start the Matthew Gfeller Sport-Related Traumatic Brain Injury Research Center. Today, the center employs upwards of 25 student and faculty researchers and focuses on improving sports safety through research and clinical practice.

Jason and Johna chat in the Stallings-Evans Sports Medicine Center on UNC’s campus. (photo by Alyssa LaFaro)

Maintaining boundaries

While Johna and Jason’s research foci help them to organically maintain separate spheres in the same department, they have worked hard to separate their personal and professional lives. When they began dating in 2005, they notified one of the program advisors about their relationship to stay transparent and respectful. More than 15 years and two children later, they strive to keep these boundaries to have healthy relationships with their colleagues, students, and each other.

“They have this amazing ability to separate their professional and personal lives emotionally,” says Meredith Petschauer, a professor in the department since 1996. “Jason’s office is across from mine, and I’ll say something like, Oh, you probably already know this because Johna told you. And he’ll say, No, Johna didn’t tell me. They really keep work at work and home at home.”

They rarely sit together during faculty meetings and often have differing opinions during research discussions.

“I have seen the two of them have a disagreement in a thesis meeting over what to do from a research standpoint and thought to myself, I can’t believe they’re not mad when they go home,” says Petschauer, with a laugh. “But they’re just not. They have this ability to compartmentalize that. How they interact professionally is not related to how they interact personally.”

“We’ve worked really hard over the last 15 years to establish those parameters,” Jason says. “Some of our biggest disagreements have been in the same room with dissertations and thesis committees, because we disagree scientifically sometimes. And that’s normal. We would do that with other colleagues, and we would agree scientifically with other colleagues.”

That said, they find many strengths in their partnership — from the logistical convenience of having similar schedules for family vacations to shared empathy for the stresses encountered in the university environment.

“When we talk at home of how work is affecting us personally, we understand what that is,” Jason says. “We know the stress of tenure. We know the stress of grant deadlines. We know the stress of campus politics.”

Their shared experience also allows them to bounce research ideas of one another and collaborate on projects.

“It is really fun to be able to work together,” Johna says. “I would collaborate with Jason even if we weren’t partners. His interests are very different from mine, but his approach is incredible, and he has done so much great work. I think recognizing the brilliance and intelligence of the other person in the workspace — and also seeing that at home — is something that helps us navigate a situation that could be awkward or challenging.”