Chocolate, coconut, and malt vinegar. Roasted Rhubarb, cream cheese, and passionfruit. Pineapple, guava, and meringue. Hungry yet?

In May, pastry chef Paola Velez combined these flavors to create a series of themed — and delectable — donuts for a Washington, DC.. pop-up event called Doña Dona, which raised $1,000 for the immigrant rights organization Ayuda. Furloughed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Velez quickly realized that she could multiply that amount by teaming up with other pastry chefs. As civil rights protests began to spread across the nation, a social media movement was born: #BakersAgainstRacism.

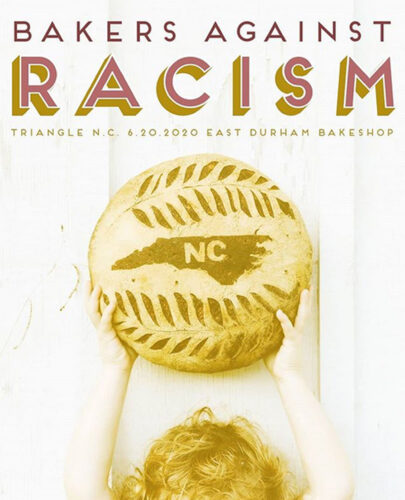

The idea was to use Instagram to attract bakers and cooks of all levels who wanted to use their talents to support the ongoing civil rights protests. The goal was for each participant to sell 150 items and donate their profits to a charity that supports Black lives.

Hysmith co-organized the Durham edition of the #BakersAgainstRacism virtual bake sale, which featured goods from local chefs and home bakers.

This sentiment resonated with thousands of people across the country and quickly made its way to Durham, North Carolina, where bake sale organizers raised over $5,000. The entire movement raised more than $1.7 million.

“Bake sales have funded things throughout history: the women’s rights movement, the reproductive rights movement. Typically, women were taking charge of them — baking the food, selling it, organizing the event, getting the word out. And then you have this modern iteration of that, which just blew everything out of the water,” says K.C. Hysmith, one of the organizers for the Durham event.

Hysmith, a PhD student in the Department of American Studies, has been interested in the politics of food since earning her master’s in gastronomy and becoming a food writer in Boston in 2014. At the time, according to Hysmith, few publications were discussing how food affects class, gender, race, and socioeconomics — and she often had to fight to write about those topics.

“Today, there’s this great reckoning with food,” she says. “But back then, there were still so many readers and magazine and newspaper heads who didn’t want to hear about food and politics or food and gender or food history.”

Since Hysmith has long been ahead of the curve in this field, it’s no surprise these topics have become the focus of her dissertation, which she hopes to turn into a book and public-facing website — and, ultimately, a job with a museum where she could develop exhibits and program.

Hysmith often focuses on food “herstory,” how women have used food throughout history to earn freedoms. Her research begins with one of the most famous battles in U.S. history: the fight for the right to vote.

Soups and salads for social change

An old adage says: “When you don’t know what to do, do what you know.” When women first began pushing for the right to vote in the late 19th century, they turned to a familiar chore to champion their cause: cooking.

The first American suffragette suffragist cookbook was published in 1886 — and would soon be followed by half a dozen more until the passage of the 19th Amendment in 1920. These collections of recipes had two functions: Women traded them for room and board while campaigning for candidates who were endorsing the female vote, and they were a form of propaganda in their fight for voting rights.

The Women’s Political Union debuted its first suffrage lunch van outside of New York City’s municipal building in April 1915. This article from The New York Tribune details the event and describes the “gorgeous” green, purple, and white wagon, which was covered with the text “votes for women” — and was even stenciled onto the roof.

“So there’s actual rhetoric in the cookbook itself, not just the person handing the cookbook over,” Hysmith says. “Sometimes it’s tucked into these essays in the back of the cookbook. Other times it’s very blatant in the names of the recipes, like Rebel Soup or Suffragette Salad.”

Women used the cookbook to argue that they needed the vote to be better mothers and housekeepers, to be more empowered to take care of the kitchen.

“They wanted to have a voice in the politics of the home,” Hysmith says.

In the 10 years leading up to the 19th Amendment, women across the nation leaned especially hard on the connection between the vote and food labor, Hysmith points out. Food quality, sanitary working conditions, and the cost of living were central issues of the suffrage movement. Wealthy, white women opened restaurants and hosted luncheons and banquets, while others created “lunch wagons” dispensing literature and sandwiches to push against elitist restaurant culture.

“The movement aimed to make the ‘unthinking mass’ of citizens see the connection between the ballot and the cost of living,” Hysmith says. “To this end, suffragists showed how women’s involvement could ‘clean up’ food as they sold slices of pie, cups of coffee, and ‘suffrage lemonade’ from their specially decorated lunch wagons.”

Hysmith gives examples of modern women who used similar methods to draw attention to their causes. In 1977, the National Association of Girls and Women in Sports (NAGWS) published a cookbook as a farewell to the tradition of selling cookies and punch to support female sports and athletics programs. Written as a parody of the organization’s various sports guides, the book featured recipes from tennis legend Billie Jean King, feminist Betty Friedan, and comedian Carol Burnett. Proceeds were donated to the American Alliance for Health, Physical Education, and Recreation, as well as other NAGWS projects.

“This ‘guide’ purposefully distanced the organization from antiquated domestic rituals while simultaneously embracing a relationship with food and their members who still liked to cook and bake,” Hysmith says.

Today, as the food industry remains dominated by men, women continue to use their creativity to get a seat at the table. Many start their own food organizations such as Women in Ag — an annual, two-day conference hosted by N.C. State University and led by women to share knowledge about sustainable agriculture and food systems practices.

Have Your Cake and Vote, Too

During the elections that took place in 18th-century New England throughout the early years of the United States’ formation, people descended upon major cities to cast their votes. While awaiting results, each city hosted parties and parades for entertainment. These spirited affairs included visiting local taverns for drinks and food — and one baked item, in particular: election cake.

“Far from a cake by contemporary standards, this would have been more of a sweetened yeast bread filled with dried fruits and spices,” Hysmith says. Recipes for the cake appeared in cookbooks throughout the 19th century. Here’s one from “The Woman Suffrage Cook Book.”

Mother’s Election Cake

5 lbs. flour

6 eggs

2 lbs. sugar

1 pt. yeast

¾ lbs. butter

1 qt. sweet milk

¾ lbs. lard

6 nutmegs

Take about three pounds of flour and one-third pound of sugar and stir up with the yeast and two-thirds of the milk. Let it rise overnight or until it begins to fall on the top. Add the rest of the ingredients and bake in loaves for about the same time as you would bread. For a more modern version of this recipe, check out this one from Owl Bakery.

Digital desserts to fight discrimination

All of the #BakersAgainstRacism bake sales took place online due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The Durham edition gave buyers the choice to donate to one of three local Black food and agriculture organizations — the Southeastern African American Farmers Organic Network, Sankofa Farms, and Land Loss Prevention. After more than 20 bakers whipped up their wares, Hysmith and collaborators organized order pick-up in a safe location that allowed for proper social distancing.

The final chapter of Hysmith’s dissertation unpacks how women use digital spaces to support their actions in real-life food work. Digital marketing and communications is often undervalued and underrepresented and has the same pitfalls as food does, she says. Women, specifically, engage more often in social media, blogging, and other forms of digital content creation for income and social support.

Online activism receives much criticism and has even been called “slacktivisim” at times, according to Hysmith, who vouches for its value. “Women who are at home with their kids have to multi-task constantly and can’t go out to protests or be on the phone all day making calls to representatives,” she explains. “These digital spaces serve as another useful outlet for political commentary and real action, particularly for people who face significant obstacles to traditional methods of activism.”

Hysmith argues, for example, that some Instagram influencers — established users of the platform, usually with hundreds of thousands of followers — use the social media site as a form of “feminist collaboration and subversive resistance to commodity culture.” She believes this is especially true for female users who have been excluded from traditional capitalist economies. After all, women make up 77 percent of influencers across all social media platforms, according to a 2019 report, and are more likely to identify as “influencers,” whereas men prefer “digital content creators.”

While she doesn’t like to openly admit it, Hysmith herself is considered an influencer. With more than 100,000 followers, her food-focused Instagram page was once “a significant portion of [her] bread-and-butter,” she shares.

“Women who manage influential food-focused Instagram [accounts] feed labor at the intersection of the digital sector and the food industry, two traditionally male-dominated field s,” Hysmith writes in a recent paper. “Unpacking the masculinized narratives that are foundational to both culinary and digital history helps us understand the precarity women face when working in either field.”

Throughout American history, Hysmith points out, women cooked domestically and men cooked professionally. And Hysmith wants to stir the pot, using food and her research to stimulate conversations about discrimination within the industry.

Digital food spaces have been more important than ever amid the pandemic, which has pointed to other problems in the industry, according to Hysmith.

“I think every decision we make has an extended food decision, and the pandemic can tell us about that,” she says. “Frontline workers are grocery store workers, are people who pick, deliver, or make our food. The food system flaws have been really exposed by the pandemic and, to me, those flaws have larger implications about race and class that, hopefully, aren’t avoidable anymore.”