When you ask Michelle Itano how she first fell in love with microscopes, her whole face lights up. She quickly tumbles into a story about attending a two-week summer program at the University of Denver, close to her hometown in Boulder, Colorado, where she became absorbed in an embryology course, marveling at the movements of sea urchin eggs being fertilized on the petri dish in front of her. She was lost in the science — like Alice in the rabbit hole.

“Those two weeks felt like forever to me,” Itano says. “It was my first continuous academic experience — and I loved it.”

She was just 12 at the time. More than two decades later, that youthful excitement still pours from Itano as director of the Neuroscience Microscopy Core at UNC-Chapel Hill.

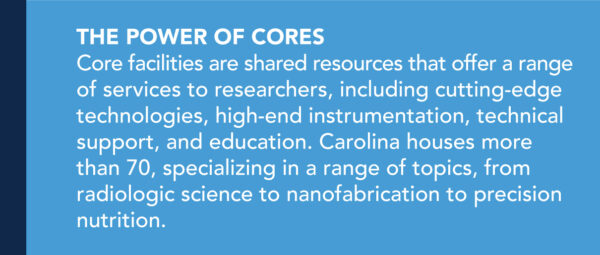

On the fifth floor of the Mary Ellen Jones Building on UNC’s medical campus, Itano greets me with a big smile. She’s wearing a purple shirt with a drawing of a microscope on it and a pair of Chuck Taylors that shimmer between violet and blue depending on the light — not all that different from the colors used to create the fluorescent imaging her core facility is known for.

Most people are probably familiar with the small tabletop microscopes they used in their high school biology class. These are called compound light microscopes, which use an eyepiece, set of mirrors, and multiple lenses to magnify objects.

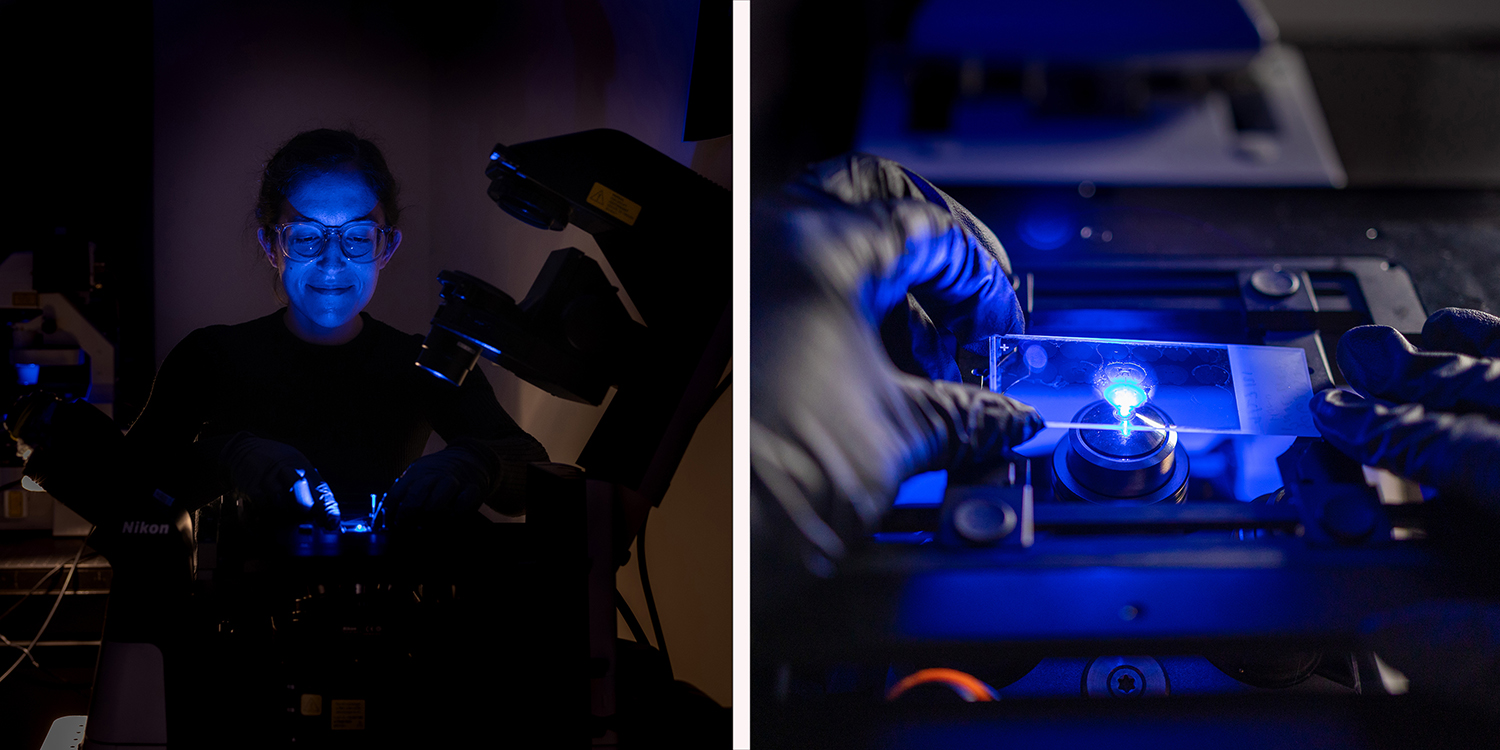

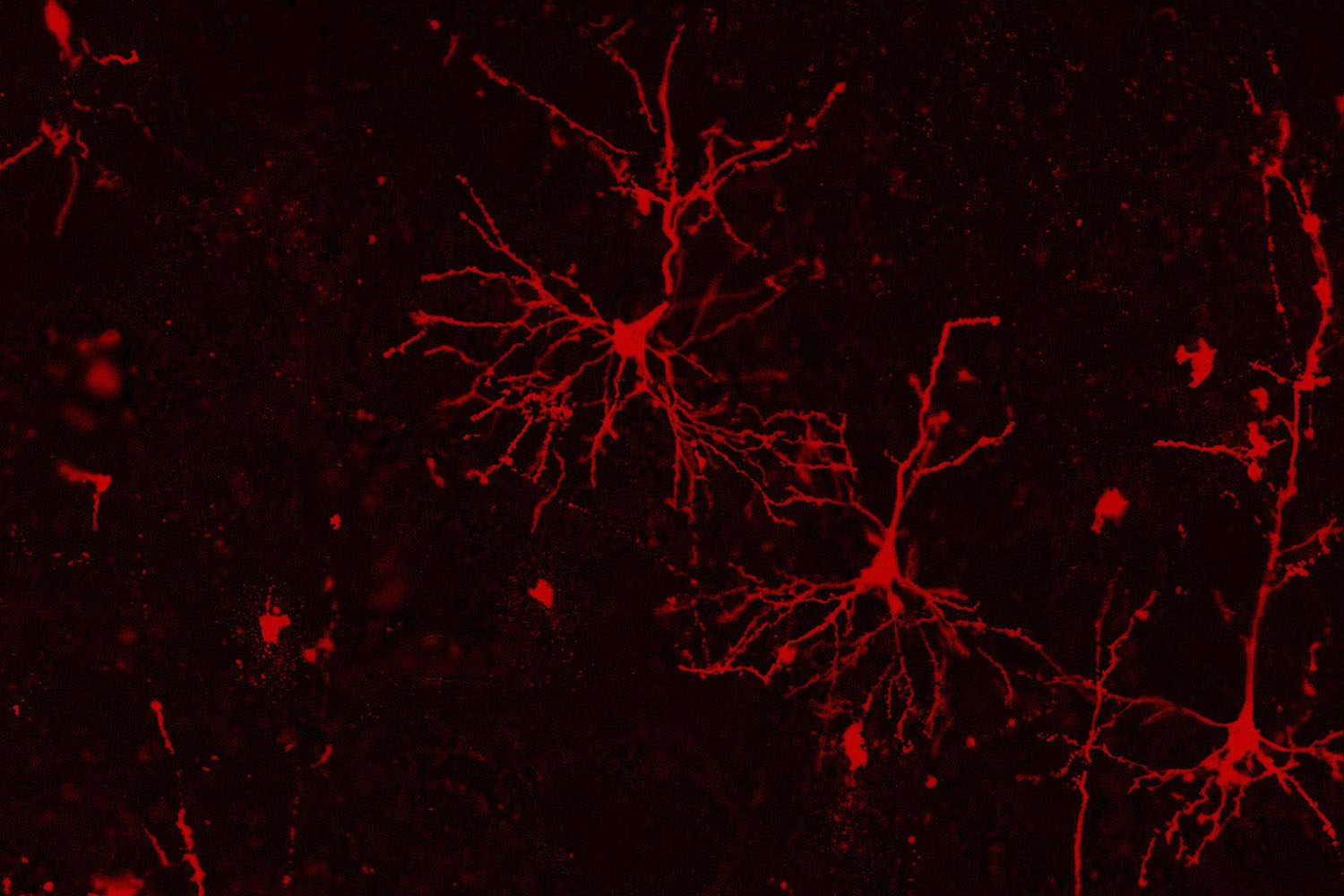

Itano specializes in the fluorescence microscope, a light microscope that uses various wavelengths — or colors — of light that interact with dyes. Users “paint” specific parts of their specimens with these dyes so that when they are illuminated, only the painted structures appear while everything else remains black. And they can use multiple dyes to stain different parts of their specimen, creating an image not all that different from an abstract piece of art.

These microscopes allow users to see deeper, with more detail than ever before. Previously, researchers would need access to multiple microscopes to capture a variety of images at different scales. Now, thanks to improvements in the technology, those scales can be achieved with the same instrument.

“You can go from a whole organism down to a single molecule, and close to atomic levels,” Itano says.

As director of the Neuroscience Microscopy Core, Itano teaches researchers how to take beautiful, complex images, assisting them with data analysis, image processing, problem-solving, and tailored advice for their specific projects — similar to how an IT professional might help you troubleshoot your computer problems.

“But like a really personable IT professional who spends a lot of time with your computer,” says Todd Cohen with a chuckle.

As a UNC neuroscientist, Cohen has used the core’s services often. He believes Itano is the reason it’s so successful.

“She is essential,” he stresses. “She brings the whole community together.”

Itano’s office walls are covered in sticky notes with reminders of her goals and tasks. In a way, they represent her many connections across Carolina — and the world. Whether she’s seeking a specialty microscope like the one housed at a National Institutes of Health lab in Bethesda, Maryland, or a technique that’s been perfected by scientists in Germany, Itano will find a way to bring those tools and skills to UNC.

Drawn to the light

In 2006, after interning with a fruit fly lab in high school and then working with researchers contributing to the Human Genome Project in college, Itano came to Carolina primed to pursue a PhD program. She studied a family of proteins immune cells use to recognize and respond to pathogens like HIV, Ebola, and Dengue within the lab of Ken Jacobson, a cell biologist known for his innovative use of a microscope technique called fluorescence recovery after photobleaching.

“He was also incredible at connecting people,” Itano says. “At the time, I got to take three or four trips to collaborating labs, acquire data there, and see other ways that people were using microscopes and facilities.”

These experiences helped Itano get a postdoctoral research position at a lab one floor above a microscope mecca: the Bio-Imaging Resource Center at Rockefeller University, one of the world’s most comprehensive facilities for state-of-the-art microscopes and scientific imaging. Using the custom-designed microscopes in her lab, Itano was exposed to a variety of research projects and the creative ways researchers use these tools to see their science.

Christina Moore, a microscopy research specialist in the UNC Neuroscience Microscopy Core, looks at a slide under the microscope. (photos by Andrew Russell)

That excitement, and all those microscope connections, brought Itano back to Carolina in 2018 to lead the UNC Neuroscience Microscopy Core.

“When I look back, I realize that the common thread from all my research experiences was the images,” she says. “I liked going back in and pulling out more data from the images — what we call ‘data mining’ now. I still get excited about this when I use a microscope. How can we get more out of the images we already have?”

Today’s microscopes produce “a crazy amount of data” that’s easier to analyze because image processing has improved. Previously, analysis could take months to complete. This is where Itano’s shifted much of her focus. How can we improve data sorting, sharing, and security?

Itano has partnered with Dalton Scott, a technology support analyst in the UNC School of Medicine, to write a chapter on data movement. Another collaboration with the school’s IT department has led to a pilot installation of an imaging database server that’s web accessible so users can browse their images online.

“People are spending hours analyzing and processing data,” she says. “Because the more data-rich images we have, the more powerful the research. And we need to figure out how to communicate it better, how to share it better.”

Helping others “see”

“Microscopy is an art form,” says Todd Cohen, the neuroscientist who has utilized Itano’s expertise time and time again. “Not everyone is great at taking images, but when you have people who are good at it and microscopes that are good, it’s an awesome combination.”

Most recently, Cohen — who studies how the buildup of a protein called tau relates to Alzheimer’s disease — and his lab have utilized the core’s services to identify “giant spheres” in the brain thought to be waste-removal centers called corpora amylacea. Now that they’ve located and imaged them, they are slicing them open to see what’s inside: piles of tangled tau proteins.

“We can almost walk you through a brain tissue sample and point out hallmarks. That’s something we wouldn’t have been able to do five years ago,” Cohen says. “The images are remarkable.”

Jason Stein, another UNC neuroscientist, uses the core to take images of intact brains to learn how genetic variation affects brain structure and increases the risk of developing psychiatric illness. By passing light through the brain of an animal model, Stein can see all the way to the nuclei in each of its cells.

“Michelle is amazing,” he says. “She can guide us in what we need and is connected to all these other microscopists across the country, which is great because there are certain microscopes we need for certain purposes.”

Madison Rose Glass, a graduate student in Stein’s lab, used a technique called Golgi staining to highlight cortical neurons in post-mortem human brains. This image is one of many that will be used to count differences in synaptic spines — the connections that a neuron has to other neurons — from people of different genotypes to determine if certain genotypes lead to more or less neuronal connections. (image courtesy of Jason Stein)

Stein and his lab need a microscope that’s quick at imaging very large samples at a specific resolution to detect small features like nuclei. And not just nuclei, but nuclei that are densely packed together — which occurs often in the brain. Through her contacts, Itano found one that’s powerful enough and wrote a grant to bring it to Carolina to help support the research of Stein, Cohen, and others.

“Everyone is super jazzed about this microscope,” says Stein with a laugh. “We’re really lucky to have Michelle at UNC.”

Neuroscientists aren’t the only ones benefitting from Itano’s microscope magic. She works with researchers all over the university, from dentists to gastroenterologists to cancer researchers. People who utilize the core are always working on vastly different projects, and Itano delights in this fact.

“It just leads to the collaborative spirit between different departments and schools at the university,” she says.

Connecting microscopists

Itano’s ever-useful microscopist network is possible, in part, thanks to a Chan Zuckerberg Initiative (CZI) grant she received in 2019. She is the first person at Carolina to accept an award from CZI. This unique funding has enabled her to hire two full-time staff members and tap into the wider microscopy world online.

“I love the microscopy Twitter community,” she shares. “They are incredible at doing science tweetorials and cool videos explaining new techniques. And there’s #flourescencefriday and #microscopymonday, and it’s fun because people at any level can connect with them.”

Itano works closely with numerous organizations — including the Light Microscopy Core Facility at Duke University, Harvard University’s MicRON core, and BioImaging North America — to support imaging scientists in North Carolina and all over the world.

“A lot of outreach happens in the microscopy community, and it doesn’t matter if it’s happening in Europe, or Latin America, or Africa. We just connect online and can, hopefully, visit each other in person in the future,” she says. “This field is so resourceful — and that makes it really fun.”