Therefore, let the moon

Shine on thee in thy solitary walk;

And let the misty mountain-winds be free

To blow against thee: and, in after years,

When these wild ecstasies shall be matured

Into a sober pleasure; when they mind

Shall be a mansion for lovely forms,

Thy memory be as a dwelling-place

For all sweet sounds and harmonies.

-William Wordsworth, English Romantic poet

In 2016, more than 44 million Americans hiked and/or backpacked throughout the United States, according to statistics portal Statista. Today, going for a walk in the woods is an American pastime. But, in truth, it’s one that’s still very young — it wasn’t until 1933 when the U.S. Forest Service deemed hiking a recreational sport in its annual report.

The concept of walking for pleasure began in the 18th century. “Before that, walking was something only the poor did,” UNC historian Chad Bryant explains. “It was a marker of social standing. Members of the nobility would travel using carriages, while the rest of society walked — and almost never for pleasure. It was done mainly for practical purposes.”

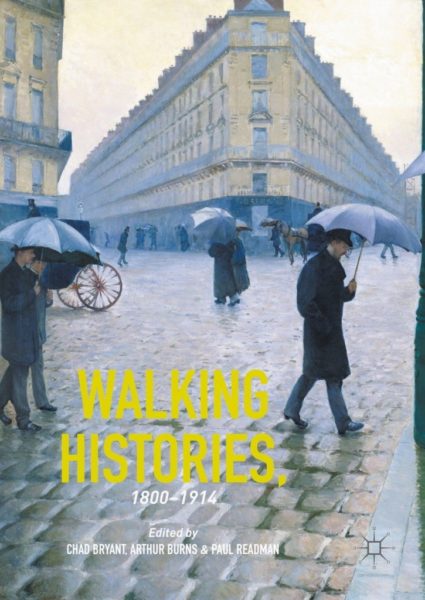

Bryant, along with King’s College professors Arthur Burns and Paul Readman, discuss this topic in a new book of essays titled, “Walking Histories: 1800-1914.” Each essay focuses on the historical significance of walking in Great Britain as well as Eastern Europe, Russia, South Asia, and Australia. Each author’s piece moves well beyond the romantic walk — “a poetic appreciation of the sublime and picturesque” — to ask how walking became embedded in the modern experience more broadly. Bryant’s essay, specifically, focuses on how walking transformed the middle class in 19th-century Prague.

The walking class

In the early 1800s, improved road systems led to a decline in highway robbery, making travel safer. This new infrastructure included the first sidewalks and gas lamps, encouraging people to explore their cities beyond the limits of daylight. During that time, cities across Europe experienced a rising middle class — a group of people who thoroughly enjoyed the benefits of their new status. Taking heed from aristocrats, who often walked in their private gardens, members of the middle class erected public parks and began exploring the countryside.

“To be middle class meant to obtain financial and social respectability through a set of practices often borrowed from the nobility,” Bryant writes. Although Prague’s middle class did exactly that, they also sought to distinguish themselves. “So they’d dress up in a nice frock and walk through the various parks on the weekends,” he says. This separated them from both the upper class — who strolled all week long — as well as the lower class, who walked mostly to commute to work.

Middle-class walkers were, especially, social and would go so far as to consult advice books to guide their leisurely promenades. “A respectable stroller kept more than two metres apart from new acquaintances,” Bryant explains. “The most intimate friends and family members went arm-in-arm. Idleness, combined paradoxically with an upright stance and stiffness of limbs, distinguished the walk. Talking points such as gothic ruins, Chinese bridges, monuments, memorials, and garden gnomes provided material for conversation.”

Fashion also played a role. Men donned specially designed walking hats and tobacco bags, while women flaunted new gloves and umbrellas — the latter derived from the noble practice of carrying a dueling sword. Even the children came along, accessorized by all sorts of rolling toys, dolls, and butterfly nets.

From promenade to protest

During the late 18th century, the rising middle classes also began putting one foot in front of another simply to admire the beauty of the natural world. They “wandered less purposively, seeking repose and solace among moors, mountains, beaches, ruins, and villages, and other places that breathed of older, less urbanized ways of life.” Whether this developed as a product of the Romantic Era or came before it is to be debated, but soon enough writers like William Wordsworth, John Keats, and Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote prodigiously about their experiences in nature.

Beyond nature walks, walking became a political tool derived from the procession — a parade honoring a king or queen before their coronation. Public protestors marched across cities carrying placards and shouting singsongs until they reached a planned destination, where their leaders would deliver a moving political speech. “But, in some ways, the march was more important than the speech,” Bryant says. “It created this sense of solidarity. It was as public display of power — taking back the streets.”

On International Women’s Day in February 27, 1917, for example, female textile workers in St. Petersburg, Russia, marched from their factories chanting, “Bread!” in response to the scarcity of food. For the next few days, more than 500,000 men and women participated in demonstrations throughout the city, setting in motion events that would lead to the Russian Revolution.

By the end of the 19th century — when it became more acceptable for women to walk unaccompanied — foot traffic overwhelmed city streets. Strollers saw cities as a place “to socialize, seek out sex, and visually consume urban scenes and spectacles.” In April 1895, for example, thousands of people visited the Paris Mortuary to view two young girls who had become victims of the Seine River, something that was “symptomatic of the larger practice of walking to view dead bodies on public display.”

Thankfully, the evolution of walking also led to other, more positive developments like the creation of public museums. The Louvre, for example, remained a private museum of the royal family up until 1793, when it was eventually opened to the public. Golf grew in popularity as well — by 1909, more than 89 golf clubs resided in London alone. The first guidebooks for walkers were printed in the 1830s. Today, travelers can search through hundreds of titles for almost any excursion of their choice, and magazines like Backpacker and Backcountry are evidence to an entire industry that’s developed around the practice.

“Walking formed the fabric of the modern experience, whether commuting to work, enjoying a guided tour, or window-shopping,” Bryant says. “But the significance of walking stretches back much farther, of course. Some would argue that we only became human the moment in which our ancestors stood upright and put one foot in front of another. Only then could we truly begin to manipulate our hands, make tools, and transform our environment.”

Stepping into the present

As walking evolved, so did transportation technology. Although it would seem that public transportation, motor vehicles, and airplanes would hinder walking, it actually caused the practice to become something else entirely. In the 19th century, railways and travel agencies “urged the harassed city worker to make a swift getaway to ‘unspoilt’ nature around which to ramble.” Today, it’s much of the same. Families travel the world to places where the train system allows them to walk from place to place and easily hop from one country to the next. The concept of the road trip encourages multi-destination excursions with spurts of city-walking and exploring in-between miles of roadway.

The popularity of hiking today is proof that the romantic walk continues to thrive. “People still like to hit the trails to escape civilization and enjoy the beauty of nature,” Bryant says. In truth, as society becomes more and more tech-savvy, it makes sense that people will continue to find the need to disconnect. “Our world needs more real, thoughtful engagement — not the passivity and isolation that comes from staring at screens or driving along over-crowded roads,” Bryant shares. “And I am optimistic our society realizes that.”