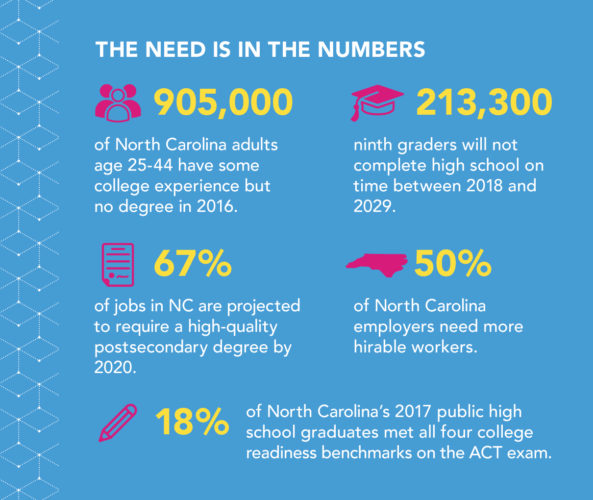

In North Carolina, high school graduation rates are at a record high, and the state’s college statistics appear to mirror that: 47 of the population aged 25 to 64 holds a postsecondary degree. By 2030, that number is predicted to rise to 56 percent, an impressive figure considering that, nationwide, bachelor’s degree attainment hovers at 33 percent.

At first, these numbers seem impressive. But take a closer look and you’ll discover that disparities in college attendance outweigh high school graduation rates. Many of North Carolina’s highly educated workers come here from other states and countries. And if current trends continue, Hispanic, American Indian, and African American adults will fall even further below the state average in overall attainment.

Earlier this year, these statistics were published in the North Carolina Leaky Educational Pipeline Report, a demographic guide produced by Carolina Demography — a unit of the UNC Carolina Population Center — and the John M. Belk Endowment.

The report portrays education as like a pipeline with a series of fittings where transition periods occur, such as middle school to high school or high school to college. But the fittings where those pipes connect leak, and students get lost in the drip tray.

Providing an in-depth look at each transition point within the pipeline, the report will now inform opportunities to increase postsecondary attainment across North Carolina.

Providing an in-depth look at each transition point within the pipeline, the report will now inform opportunities to increase postsecondary attainment across North Carolina.

“We didn’t have a big, clear picture of how all the pieces in the system were linked up together,” says Rebecca Tippett, director of Carolina Demography and a lead on the report. “So this project was a way to understand the connections in the broader system of education.”

On the surface, according to Tippett, regional statistics for the state look respectable. But upon peeling back the layers, large gaps begin to appear. For example, the North Central Region, home to Raleigh and the Research Triangle, shows seemingly positive educational outcomes like strong graduation rates and immediate college enrollment.

“But it has some of the widest gaps between white students and black and Latino students of any region in the state,” Tippett points out. “And it’s not just because white students are doing well. It’s because minority students are doing worse than other students elsewhere. That was a startling finding that highlighted the need for looking beyond averages and, instead, at group differences and how gaps play out across regions.”

While the findings are alarming, the good news is that UNC researchers in the fields of education, public policy, and law have been hard at work for years to address these issues and try to change them, developing programs for preschool-aged children all the way up to college graduates.

Strategies for teachers

In 2016, Yale researcher Walter Gilliam conducted a study where early childhood educators watched a video of preschoolers and tallied the number of challenging behaviors exhibited by the children. What the teachers didn’t know is that these kids — a white male, white female, black male, and black female — were actors, and that Gilliam was utilizing eye-tracking technology to identify where these teachers focused their attention.

Educators looked at the African American boy 42 percent of the total time in the classroom and indicated that he displayed significantly more challenging behaviors than the other children. What’s more, both white and black educators produced similar reports.

“They were looking for something to happen with him whether they realized it or not,” says Sherri Williams. “That study spurred national attention on this fact that we do have a problem with preschool children being disproportionately disciplined, suspended, or expelled based on their race.”

Williams oversees the North Carolina Early Learning Network (NC-ELN), a program through the UNC Frank Porter Graham Child Development Institute (FPG). The network provides early learning communities with professional development and technical assistance to support preschool children with disabilities.

Williams and her team create training materials on effective instructional practices supporting the emotional and social development of children, which includes how to address challenging behaviors such as rough play, poor listening skills, or difficulty taking turns and emphasizes how implicit bias affects how educators respond to these challenging behaviors. They also provide training to coaches who ensure this knowledge is transferred to the classroom.

The basis for this work stems from the Perry Preschool Project and FPG’s Abecedarian Project, the world’s oldest long-term study on early child care and education. Focused on mostly African American children from low-income families, the Abecedarian Project has shown that kids who receive high-quality educational intervention from infancy through age 5 have a better rate of success later in life.

“We are building the foundation for preschool children socially and emotionally to set them up for success from kindergarten through graduation,” Williams explains. “The ultimate goal is not to take the child out of the classroom. It’s to teach the child what he or she needs to know in order to participate effectively, to regulate behaviors, to learn social skills.”

Lessons in leadership

When Ricky Hurtado and his family moved from California to Sanford, North Carolina, in the mid-1990s, the population was just 5 percent Latinx. Today, it’s 25 percent.

“The community is really grappling with what it means to see this transformation in 20 years,” he says. “So our students get a lot of negative messaging about who they are and what they are capable of. I think being able to turn that narrative on its head is important so they can have a positive relationship with learning and education.”

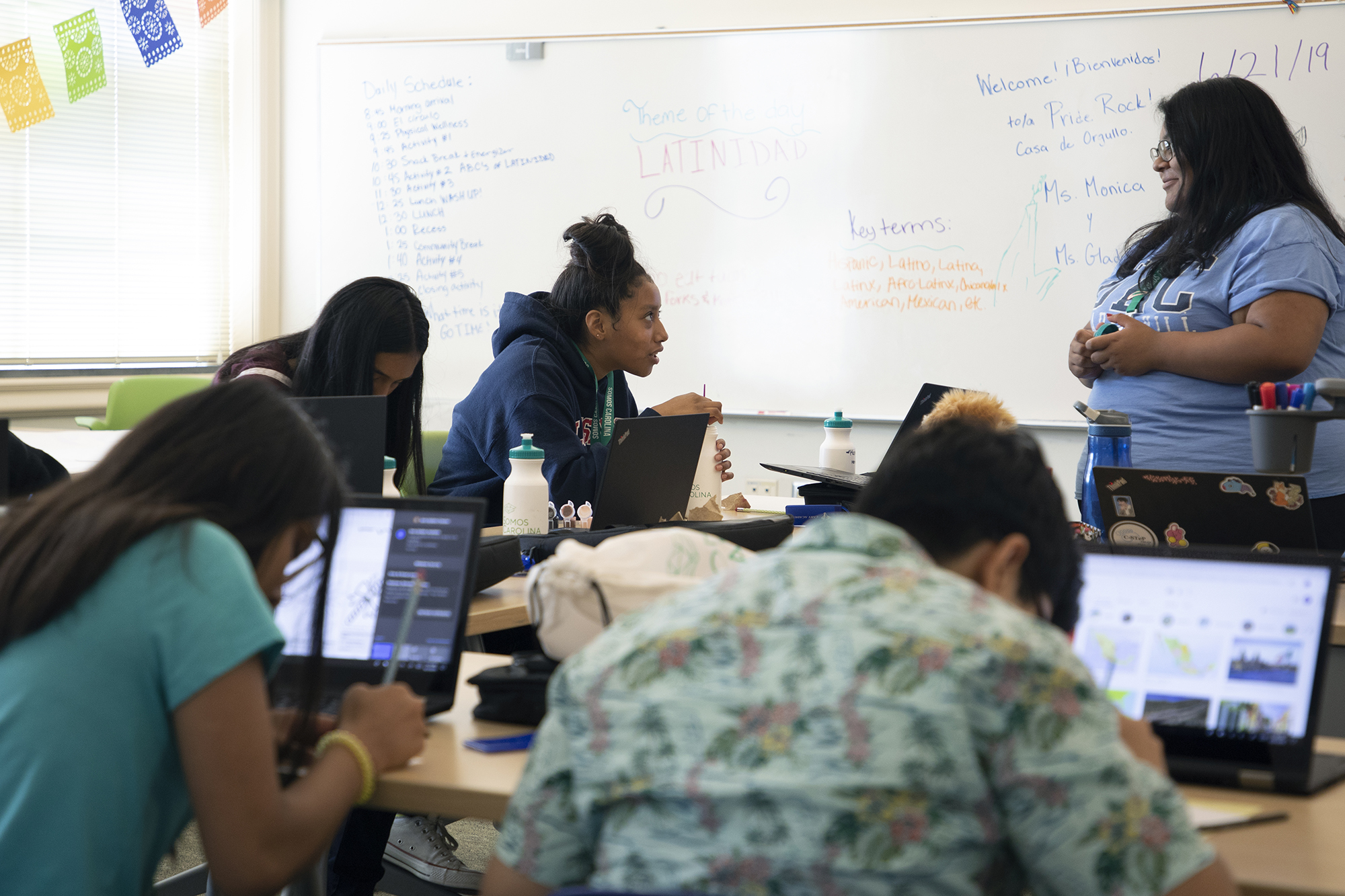

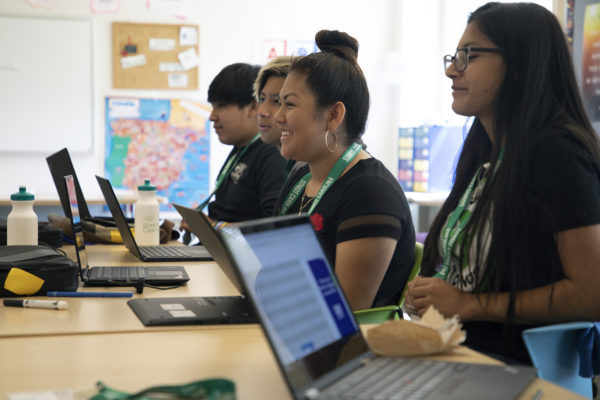

Today, the Princeton graduate runs LatinxEd, a UNC collaboration and nonprofit focused on building leadership skills among Latinx youth within their communities and schools. This past summer, he and his co-executive director Elaine Townsend Utin kicked off the newest program of the organization, Somos Carolina — a three-week day camp focused on Latinidad (Latin culture), learning, and leadership. The goal of the program is to help students preparing to enter eighth grade develop a strong sense of self, identify with their culture, and view themselves as both learners and leaders.

Eighth graders participating in Somos Carolina this past summer listen to peer presentations on Latinx culture.

“Doing this before they go to eighth grade is an awesome opportunity because we get to have these conversations earlier,” Utin explains. “For me, it was probably a conversation I started having in college. My life would have been so different if I had the language to express myself and who I was, my family’s history, and where we came from.”

Utin, who grew up in rural North Carolina, adds that living in a predominantly white space made it harder for her to connect to her roots when she was a kid. “We’re really trying to build this support network and this community that students feel like they are a part of something greater than themselves, but also part of their community,” she says.

UNC senior Verenisse Ponce-Soria agrees with Utin and stresses the importance of encouraging these messages in underrepresented students. Like Utin — and all of the camp’s teachers, for that matter — she identifies as Latinx and is one of the many program educators affiliated with UNC.

“I am sure some of these students fall between the cracks,” Ponce-Soria says. “When reviewing applications, I could tell that one student was having some difficulty with his writing. But when I was interviewing him and talking to him, he told me he got on YouTube once and learned to program in three hours. Then he went into his dad’s garage and built a remote-controlled car. That’s a talent that goes uncultivated.”

Hurtado and Utin hope this edition of Somos Carolina is the first of many going forward. This year’s partnership with Cary Academy — which not only physically hosted the program but also provided computer access, transportation, and lunches for all 60 students, free of charge — exemplifies the potential of the program’s growth.

“We’re doing a lot of painting right now, and it’s exciting to get a blank canvas again next year,” Utin says. “The first time you learn so much, and we’re excited to apply that next year. It’s such an artform, and it’s so fun.”

Data to push policy

When Anayancy Estacio-Manning began her first year at UNC, she brought 60 college credits with her. Now in her third year, she will graduate this coming May — an entire year ahead of schedule. That’s because she attended Cross Creek Early College High School in Fayetteville. “I really liked the opportunity that was afforded to me by going to an early college,” she says. “It made me feel more prepared for UNC and it has really helped with the cost since I can graduate early.”

Early college high schools blend high school and college courses so students graduate with both a high school diploma and up to two years of college credit — at no additional cost to the students. With nearly 90 across North Carolina, they are some of the state’s most successful schools, producing high graduation rates and test scores.

“Early college high school graduates are much more likely to finish an associate degree,” says Doug Lauen. “They’re also more likely to enroll in a four-year institution and finish a bachelor’s degree.”

As a public policy researcher, Lauen collects data from the N.C. Department of Public Instruction to build a large longitudinal database that merges K-12 and higher education information and analyze the effectiveness of both early college high schools and charter schools on life success.

“We’re trying to move beyond just thinking about the effects of schools on test scores and think about other important things like graduating, going to college, and getting a job,” Lauen explains. He’s also looked at the impact of these high schools on suspension rates, absences, incarceration, and voting.

In his most recent study on charter high schools, Lauen found no evidence of effects on postsecondary enrollment or completion. Early college high schools, on the other hand, do make a difference on these outcomes. Students at these institutions experience fewer absences and higher math and English end-of-course test scores.

“I think policy should be based on evidence, and that’s what I see as my role,” Lauen says. “I’m looking at the effects of different kinds of institutions on kids. And that’s not all. You need to consider cost. You need to consider equity, morality, and all kinds of other things, but evidence for effectiveness is pretty important.”

Funds for college

In 2014, Heather Oaks decided it was time to go back to school. As a single mom in a tight financial situation, she pursued every funding opportunity possible, but still ended up taking out student loans. “I signed up for everything I could. Medicaid, food stamps, all that,” she says in a video for EducationNC. “Because I needed to make this happen. There wasn’t another choice.”

She was in her second-to-last semester — and then her car transmission died. “And you think, Really, God? Really? One more thing? And it doesn’t take a lot to just put you right over the edge,” she says, lifting her hands above her head, “because you’re already up to here.”

UNC Charlotte awarded her with a Gold Rush Grant, which gives $1,500 to students who are almost finished with their degree, but still need some financial assistance.

Oaks’ story is not unique. Every semester, UNC Charlotte loses 670 academically eligible students, according to enrollment staff. Sixty-three percent of them have a GPA higher than a 2.5. And of those students stopping their education, 70 percent said it was because of financial issues.

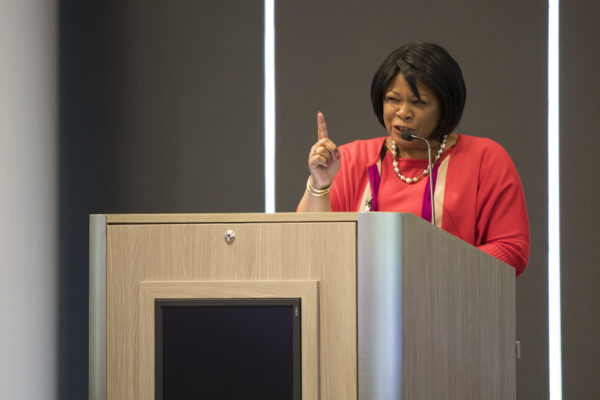

“The day Heather’s car transmission went out was the day she thought it was too many things to manage: school, her daughters, and all the other things life entailed,” says Anita Brown-Graham. “Thanks to the Gold Rush Grant, not just Heather’s life, but the lives of her three young girls have been transformed.” Just before Oaks graduated, she received a job offer from a local engineering firm.

Anita Brown-Graham addresses workforce development professionals. (photo courtesy of UNC School of Government)

A professor in the UNC School of Government, Brown-Graham leads the ncIMPACT Initiative, a public policy initiative that provides civic leaders across North Carolina with high-quality data, research, and analysis to respond to the state’s most challenging problems. Earlier this year, she and her team profiled 10 programs that demonstrate how local communities are working to increase educational attainment in North Carolina. They call these “Bright Spots,” and UNC Charlotte’s Gold Rush Grant is one of them.

Approximately 905,000 North Carolinians have not completed their postsecondary degrees or attained a high-quality certificate, according to U.S. Census data.

“A lot of these are students who end up having to leave school for nonacademic reasons,” Brown-Graham says. “They drop out, have to start working, and then never go back to complete their program. And this is particularly an issue for first-generation, lower income students who can’t pick up the phone and call home to ask their parents for help.”

By looking at why students fail to complete, ncIMPACT Initiative researchers identified barriers such as childcare and effective public transportation. Often, these roadblocks arise for students within arm’s reach — some just six months — of receiving a degree or certificate. One solution is finish-line grants like the one UNC Charlotte gave Oaks. An option for veterans specifically, according to Brown-Graham, could be converting educational experiences from their time in the military into credit hours to expedite their degree.

Brown-Graham is also looking at career pathways, or “creating a ladder that helps people go from credentials to a degree.” The nursing profession, according to Brown-Graham, is a great example, where students start as a certified nurse assistant, attending school while working in the field, and then work their way up to a licensed practice nurse. Next steps include the registered nurse designation, followed by a bachelor’s degree in nursing.

“Some of the challenge to choosing the right pathway and completing it is cutting through the noise,” she says. “This isn’t just about getting a job, though. It’s about all the benefits that come to people who are positioned to take care of themselves and their families.”