Every other Thursday, Jodi Flick walks into the library at the United Church of Chapel Hill on Martin Luther King Junior Boulevard, sits down, and waits. A stack of self-help books sits next to a box of tissues on a nearby table. People slowly filter in past the bookshelves and find a seat amongst a circle of upholstered chairs.

After the group has gathered, Flick (or one of the other five facilitators) lights two candles and says, “We light this first candle to remember the light that our loved ones brought into our lives. And we light this second candle to remind us that we are still alive. We can best honor our loved ones by embodying their light in the world.” Then, each person shares their story about how someone they love died by suicide.

Flick created the Survivors of Suicide Loss Support Group (SOS Group) in 2009 while working as a crisis counselor for the Chapel Hill Police Department. Meeting with families who lost someone to suicide was always a difficult task, and she felt like she couldn’t offer them the resources they really needed. She’d come back to the office frustrated that someone wasn’t doing more to help these families. “I would get so aggravated,” she explains. “Finally, after about four or five years, I realized that someone needed to be me,” she admits.

Today, Flick — a social work professor at UNC-Chapel Hill — has partnered with the Injury Prevention Research Center (IPRC) as a coach for its most recent Injury-Free NC Academy. Each year, the academy organizes an injury and violence prevention program to educate participants on different public health topics. This year’s academy strives to enhance North Carolina’s capacity to prevent suicide. Social workers, police officers, public health department staff, mental health professionals, lawyers, and community activists from 22 counties across the state took part in the six-month workshop to develop these skills.

Each group focused on a different target population such as high school students, the LGBT community, or the elderly. “Suicide prevention plans need to be evidence-based,” Flick says. “Otherwise, how do you know you’re using safe messaging? My role was to help them think through it. What does the research say?”

Speaking the language

The phrase “committed suicide” is extremely outdated, Flick points out. “It derives from when it was a crime — you commit larceny, commit murder, commit suicide,” she explains. “But suicide was decriminalized in the ’70s. The word ‘commit’ also makes it sound like suicide is a rational choice. Neither of these things are the case.”

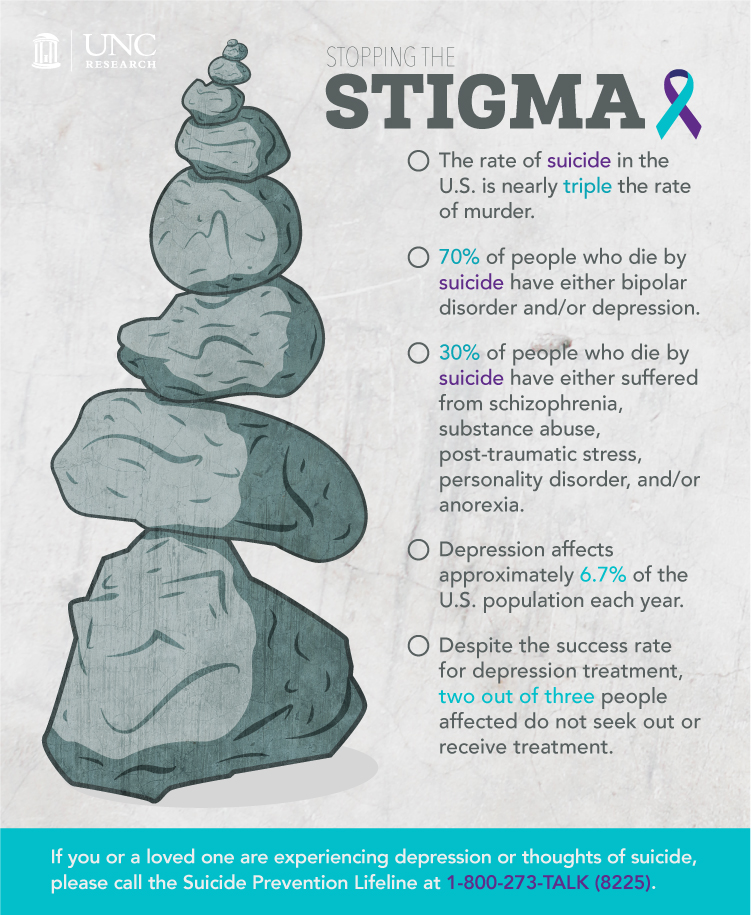

Seventy percent of people who die by suicide have either bipolar disorder or depression, according to the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). The remaining 30 percent suffer from schizophrenia, substance abuse, borderline personality disorder, anorexia, or anxiety disorders like post-traumatic stress. “These illnesses by themselves aren’t enough,” Flick stresses. “Lots of people have depression and don’t die. That by itself is not enough.”

Imagine a pile of teetering rocks. Depression and bipolar disorder are the boulders that sit at the bottom of the pile. Then, layer on a series of smaller rocks like sexual abuse, traumatic brain injury, job loss, or drug addiction. Each additional rock makes the pile more and more unstable. Eventually, it crashes to the ground.

“People look for an easy answer like, ‘Oh, well, he lost his job.’ Lots of people lose their jobs and don’t kill themselves. It might be the trigger — the thing that knocks over their giant pile of rocks — but it’s not the cause.”

Not many people realize that the rate of suicide in the United States is nearly triple the rate of murder, Flick says. “That’s because murder is on T.V. and in the newspaper every day. We keep suicide out of the media because we don’t want to sensationalize it,” she explains.

But everyone knows someone who has died from suicide. That’s why talking about it is key.

“People don’t know what to say when a loved one dies,” she says. “But they really don’t know what to say when someone dies by suicide. If you keep it a secret, you’re just adding to the stigma. You don’t keep your mother’s heart attack a secret because it wasn’t her fault. Suicide is the same way. You don’t have to give all the details, but you can certainly tell the truth.”

Flick lost her father-in-law, Jim, to suicide nearly 20 years ago. But when her husband explains his death, he’s honest. “He’ll say he died of depression and alcoholism — which is absolutely true,” Flick says. “He had a terrible illness and he died from that illness. People can’t see that in the moment. It’s too raw. But with time and discussion they can.”

Zooming in on adolescent girls

When Mitch Prinstein was in kindergarten, a group of dentists visited his classroom to teach him and his fellow classmates about dental hygiene. They chewed on special staining tablets that interact with plaque. Then, they brushed. After, the dentists inspected their teeth, many of which lit up like a neon sign — they hadn’t brushed their teeth well enough. “That was probably a 15-minute demonstration for dental health,” Prinstein, now a UNC psychology professor, points out. “We do so little for mental health. We don’t even do 15 minutes.”

Prinstein wants every kid in the state to undergo mental health screening. “I have nothing against dental hygiene,” he laughs, “but I would venture to say that, unless you have a really bad cavity, a depression screening could prevent consequences that are far more dire.”

Prinstein’s research focuses on adolescent peer relationships — how young people get along with one another, who’s popular, who’s teased, and who’s friends with whom. He’s appalled by the statistics surrounding self-injury like cutting. Approximately seven percent of middle-school-aged children cut themselves. By high school, that number increases to 15 percent — and to 50 percent in children who have been diagnosed with a mental illness.

One in five teenagers seriously considers suicide each year, according to the American Psychological Association. “Suicide is one of the most severe forms of mental illness out there, but it’s also one of the least studied,” Prinstein says. “Look at the rates of public health issues like cancer and HIV over the past 20 to 30 years. They’ve all seen dramatic decreases. But there’s been no significant decrease in the number of people dying by suicide or the number of attempts.”

Of those who attempt, 80 percent are girls. “There’s no gender difference in depression up until the age of 12, and then, all of a sudden, there’s a huge increase in depression among females,” Prinstein explains. “And it’s not just pubertal hormones — it’s more complex than that. I want to help girls who are at risk.”

In response, Prinstein is throwing all his energy into the UNC Girls’ Health Study, which will recruit girls between the ages of 9 and 14, who are suffering from sadness, depression, anxiety, stress, or related symptoms. Last year, Prinstein received a $4 million grant from NIMH to study how stressors affect DNA in relation to suicide. Stressors can activate dormant DNA that affects the production of serotonin — a chemical in the brain that impacts mood, sexual desire and function, appetite, sleep, memory and learning, temperature regulation, and social behavior. A change in serotonin levels can trigger depression and lead to suicide.

Lowering the statistics

Adolescents are impulsive, especially when it comes to suicide. “People who are older experience recurring episodes of depression and might take numerous steps before actually engaging in suicidal behavior,” Prinstein explains. “Adolescents may make the decision in a matter of minutes or hours after experiencing a severe stressor.”

That’s why Prinstein wants to uncover the stress responses directly related to suicide attempts in adolescent girls. He hopes this information will help mental health professionals and the public shut down the psychological processes that put these teens at risk.

Flick agrees that strategies need to be put in place, and discusses the work of American psychologist Tom Joiner, who recently proposed a model for why people die by suicide. “Two things that drive the desire to die are a sense of disconnectedness from other people — alienation, loneliness, feeling like you don’t belong — and feeling that your life has become a burden to the people you love,” she says. “For the first time, we can target if someone’s suicidal and then implement strategies to make that person feel connected and valuable.”

Last year, the School of Social Work received a three-year grant from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration to administer mental health first aid training to 25 percent of the faculty and staff at UNC. In January, the school began offering a day-long class that teaches attendees first aid for panic attacks, psychosis, substance abuse, and suicide. Flick and three of her colleagues within the School of Social Work lead the class.

“So if you saw a student or professional who was giving the warning signs that they were depressed or suicidal, you’d know what to ask and do to get them the help they need,” Flick says. “In North Carolina alone there are numerous groups trying to tackle this topic — it’s the first time we’ve put forth this much concentrated effort. I’ve never been more optimistic about suicide prevention than I am now.”